Jenny Jasky is Philadelphia’s loss and New York’s gain; she recently moved and already found an outlet, curating an exhibition at NYCAMS (New York Center for Art and Media Studies) with Stamatina Gregory. Incarnational Aesthetics (Oct. 24-November 25, 2009) is one of those idea-driven exhibitions where I found the work provocative but couldn’t entirely reconcile it with the curators’ statement: to showcase artists who use embodiment or ‘role play’ in their work as a means of interrogating and deconstructing the public and private boundaries between self and other.Much of the work was about other art, with Cindy Sherman and Slater Bradley assuming the guise of well-known performers, Yasumasa Morimura, Clifford Owens, Jeffrey Porterfield and Lillbeth Cuenca Rasmussen re-doing earlier artist’s works, and Michael Joo and Alex McQuilkin reenacting characters from films.

The most imposing piece, Lilibeth Cuenca Rasmussen’s How to Break the Great Chinese Wall consisted of a large set in which she re-enacted a number of performance pieces by an earlier generation of women: Marina Abramovic (and Ulay), Yoko Ono (with John Lennon), Shigeko Kubota, Yayoi Kusama, Ana Mendieta. For the remainder of the exhibition (when I visited) the set contained a video of the performances. They struck me as an exorcism of her anxiety of influence rather than anything to do with boundaries of self and other. At some point in the dialog she connected the words starving artist, consumption, and bulimia; that caught my attention for the contrasting and gendered association of those terms.

Abramovic herself recently re-staged a number of performance pieces of the 1960s and 70s, her own and those of five other artists (Seven Easy Pieces, Guggenheim Museum, 2005). The possibility that performance art can be re-enacted is certainly a critique of values long-credited to the form: the essential role of the artist’s own presence, the dependence on specific circumstances and the effect on the audience of unforseen actions ( in some cases witnessed without prior knowledge, as in the case of street performances). Is this appropriation performance, or method acting?

Yasumasa Morimura took on an artist whose influence has been so stiflingly pervasive in An Inner Dialog with Frida Kahlo (2008). I was never sure who the audience was for Lynn Hershman Leeson’s alternate existence as Roberta Brietmore (1974-78), shown here with two collages; the artist was certainly the only audience for the piece in its entirety. Tammy Ben-Tor’s video, Baby Eichmann (2008), was a suitably disturbing fairy tale of self deception, given the subject was Holocaust denial; it was played by the artist and several china figures of Bavarians in traditional dress. The exhibition also included work by Cindy Sherman, Coco Fusco, and others.

Evolution of the Cool

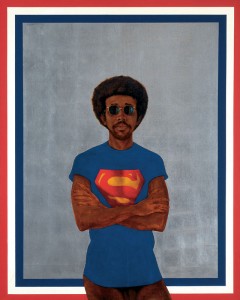

The response to the symposium Evolution of the Cool (Nov. 21), held in connection with the Barkley L. Hendricks exhibition, Barkley L. Hendricks; Birth of the Cool (through Jan. 3, 2010) was so great that the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) moved it from the usual lecture room to a large gallery on the second floor of the new Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building. The crowd was certainly an homage to Hendricks but also indicated a hunger in the area for serious discussion of African American art, I’d guess.

Symposia often promise a lot but only deliver exhaustion. This one kept up the interest because rather than having all the speakers focus closely on Hendricks and his work, practitioners from dance, music and the fashion world spoke about ideas parallel to Hendricks’ with the two academic speakers reserved for the end. The artist himself went first, saying that he’s often called a realist but would prefer to be called a prestidigitator or trickster. In describing his working methods he said he always played music in the studio: what he calls American Classical music and others term jazz.

One of Hendricks’ inspirations, Jazz pianist Randy Weston, spoke of color as visible sound while music is invisible sound; at the piano he thinks in color. Brenda Dixon Gottschild, dancer and dance scholar, made eloquent use of her hands as she delivered what she called a stream of consciousness dance through Barkley Hendricks’ works. She showed his paintings beside images of Alvin Ailey, Eleo Pomare, Steve Paxton and others. Hendricks’ nudes, she said, had her undressing any number of men in her mind. Emil De John, fashion designer, showed how he and other designers were constantly going to paintings for ideas and inspiration.

Sarah Lewis, a critic and curator who’s working on the next Site Santa Fe, focused on Hendrick’s paintings on white backgrounds. She spoke of the necessity for African Americans to construct their own identities in relation to the construction of white America, represented by the detailed particularity of Hendricks’ figures against the generalized featureless whitenes. Richard Powell, scholar and major figure in African American art history commented on the humor that was always behind Hendricks’ work which made viewers uncomfortable and the nudes that were so disturbing in the 1960s and 70s that not a single critic mentioned them.

Who, before Hendricks, had the audacity to paint a black man, as just that, a man?