With little-seen gems from Philadelphia’s historic scientific institutions, as well as side-by-side art history ground shakers including Thomas Eakins’ Gross Clinic, Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (no. 2), and Eadweard Muybridge’s early motion photographs, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Art’s new exhibition, Anatomy/Academy, rephrases the dusty argument over the continued importance of human anatomy studies in art education while touching on a number of important sub-topics along the way. Rather than advocating a backwards or stodgy interest in the figure, this exhibition shows how the study of the human body progressed side by side with new technology, and how ways of seeing, even today, are inseparable from those tools which we use to see (tools which, in the age of Google, are in a state of constant renovation).

With works from Philadelphia’s various historic collections, the exhibit, in the Fisher Brooks Gallery in PAFA’s Hamilton Building centers around three main periods: the time of PAFA’s founding as the nation’s first art school in 1805, the tenure of professor Thomas Eakins in the late 1800s, and the first World War.

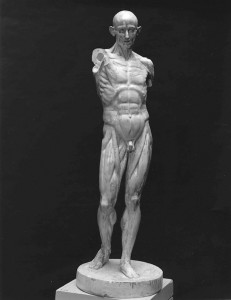

The first section of the show includes pieces from PAFA’s plaster cast collection (including Houdon’s Écorché—Flayed Man), early medical texts, and drawings that emphasize the links between the Philadelphia academy and early Italian and French arts academies, where life drawing and cast drawing, écorché* and anatomy study were central elements of the curriculum. Here, two early medical textbooks thrill with their surreal and macabre touches. A “flap anatomy” book presents human figures with body-part tabs (and even a pop-up loincloth) that can be lifted off the page to reveal their sub-epidermal structures—something like an anatomy-themed advent calendar. The other text (after Vesalius’ classic) features a skeleton with dangling veins and nerves frozen in an action pose, plunked right in the middle of a Renaissance landscape.

Also fantastic are the enormous anatomical models created by PAFA’s cofounder, William Rush, which were used as teaching models for medical students in a large lecture hall. The inner-ear, sphenoid and eyeball models, in particular, are impeccably crafted, expressive sculptural forms that fit right into the art museum context.

Across from these models hangs Eakins’ Gross Clinic, which, compared to its recent central placement in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Perelman Building, is nestled somewhat understatedly among other works. (PAFA and the PMA jointly own the painting and it travels back and forth.) A vitrine filled with Eakins’ paint box and brushes as well as several surgeon’s toolboxes sits alongside the masterpiece. The sight of the painting united with the tools of its making and the tools of the characters depicted is a rather moving; the juxtaposition implies a metaphorical connection between the surgeon’s carving of flesh and the painter’s.

Also thought-provoking is Kenyon Cox’s “Masked Female Nude”—a beautiful, if rather typical figure drawing of a female nude, striking, though, in that her face is masked (a method that we learn was used for preserving the nude female’s “dignity”.) This piece and others highlight changes in the role of women and in ideas about the nude body that took place in the arts and sciences of this time.

The section of the show devoted to the 20th Century emphasizes the importance of new technologies and medical innovations. One piece, a haunting fish-bone-like array of what appear to be branching white wires is actually the entire nervous system, painted and mounted on a board, of a Hahnemann Hospital cleaning woman—not a “model” but the real thing. Also in this section are several Eadweard Muybridge motion photographs featured along with a vast display of Eakins’ motion photographs— these images recount the meeting of these two great innovators right here in Philadelphia in 1883. These photos changed scientific history by revealing to viewers truths about form that were visible through photography but invisible to the naked eye (the famous story recounts viewers’ amazement upon learning that horses in gallop always have one leg that remains on the ground—a truth that rendered many historic paintings of horses with all legs in the air at once something of a joke).

Across from these photographs hangs the other great challenge to traditional form, Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (no.2), which, in its complete shattering of the human figure actually emphasizes the importance of understanding how to compose figurative form. Further variations on the shattered or fragmented figure are featured in the work of WWI painters, including Bernard Petlin’s graphic leg amputation paintings and Ivan Albright’s eerily luminescent Woman whose flesh seems to be in a state of disintegration.

These stronger works, however, are weighed down somewhat by other pieces whose relationship to the theme of the show is more tenuous (Robert Henri’s large females, for example).

The show concludes with a coda—contemporary pieces by Donald Lipski and the artist group TODT—which neither detract nor add much to the viewing experience.

The more exciting addendums to the show are located upstairs and downstairs: a show of work by current PAFA students in the basement and the upstairs companion show, Anatomy Now. Both exhibits showcase a variety of contemporary iterations of “figurative” work and show the way in which a figurative platform continues to birth new interpretations.

More than simply tracking a theme throughout history, this show situates a staple feature of art—an interest in the figure, and more generally, an interest in the visible, tangible, embodied world and what lies beyond it—in a greater context. It shows how artists and physicians in the 19th and early 20th Centuries both sought to make sense of life itself, and how their attempts to do this emerged very much in tandem.

This show begs us to consider, or reconsider, the relevance of figure study in the training of artists today.

Contributors to the exhibition include the Mütter Museum, the American Philosophical Society, the Wistar Institute, the PMA, and PAFA’s own permanent collection. View more of the historical material including Eakins’ sketches and one of the flap anatomy books here.

Anatomy/Academy and Anatomy Now, to April 17, 2011. www.pafa.org. Adults $15 Senior (60+) and Students with I.D. $12 Youth ages (13 – 18) $12 Child (12 and under, excluding groups) FREE

—

*Écorché – the construction of a sculpted figure which begins with the skeleton and works outward to the skin