[Andrea considers the evolution of art’s “authenticity”; museums’ fetishistic need to present original works; and the practice of replicating pieces as “exhibition copies”. — the Artblog editors]

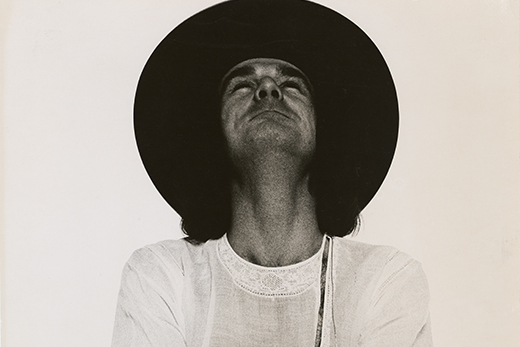

I received notice from MoMA that on August 17 and September 7, the museum is hosting performances by James Lee Byars, in connection with the retrospective of his work at P.S. 1. Since the artist is long-dead, what exactly is the museum presenting?

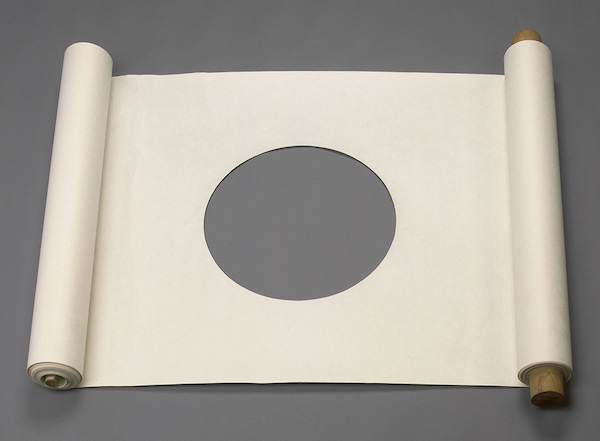

Byars did many performance pieces–indeed, his life sounds like an extended performance. Some of Byars’ performances involved another person interacting with an object of the artist’s making, and Byars donated one of these objects to MoMA. The work consists of handmade Japanese paper, attached with rivets and folded into a cube; when unfolded, it is 500 feet long.

In 1965, dancer Lucinda Childs “activated” the piece at the Carnegie Museum of Art, and she trained one of the dancers in her company to perform “Mile Long Paper Walk” on August 17. I don’t know whether Byars left instructions for the performance to be enacted after his death, but the museum announced that it would not utilize the paper piece in its collection, but an “exhibition copy”.

No repeat performances?

Byars flirted with the idea of death throughout his life and work, and he and his executors may be delighted with posthumous performances. As noted in his obituary in The Inquirer (June 19, 1997), “’This is a Call from the Ghost of James Lee Byars’” was the title of a 1969 performance by the artist. Byars anticipated his death throughout his career, death being one magnetic pole of his oeuvre–the other was perfection.

Byars set up a “Death Lottery” in the ’70s to mark his own death in advance; in 1979, he invited Salvador Dali to Hollywood in order to film his death (Dali refused) and he used death, ghosts, and spirits in the titles of his work…in 1984, he performed “The Perfect Death”.

In describing the current performances, MoMA says: “The majority of the performances in this series were developed with ephemerality in mind. As such, though many of the constituent parts remain the same as when they were first presented, nothing should be considered a ‘repeat performance’. Rather, in Byars’ fashion, each can be read as an inimitable event, unique in space and time.”

I don’t have problems with repeat performances. They are, after all, the basis of all the musical and theatrical arts. Not only were scores and scripts written for re-performance, but everyone knows this. And while each performance may have a subtly different character, that doesn’t stop plays or music from being inherently “imitable”. Museums, however, fetishize originality–note MoMA’s stretch of a description: “each can be read as an inimitable event, unique in space and time.”

Increasingly, museums present us with digital copies of films, “re-performances” that may be of questionable authenticity, or at least pertinence, when the world to which they responded is now history, and the rarely-acknowledged “exhibition copies”. It turns out that for a couple of decades, we have all been looking at recreations of unwieldy and/or fragile art, without knowing it. “Exhibition copies” are usually authorized by the artists–although I doubt that Byers has given his approval here–and are destroyed once the occasion of their fabrication has passed. Note: this is not the case with artists such as Sol LeWitt and others like him, where the artist intended the work to be executed by others, and there are no prior “originals” executed by the artist.

Assigning value to originals

I think copies have a lot of value, particularly for teaching purposes. After all, a three-dimensional copy is infinitely more faithful than a two-dimensional, photographic copy, and I’m grateful to see performances in the style of Isadora Duncan when they are recreated with scholarly rigor. MoMA is making effective use of copies in the current exhibition of Lygia Clark, with recreations of sculptures that can be manipulated by visitors, as intended for the originals.

But museums base the importance of their collections on the premise of authenticity. With artworks that can be re-fabricated by the same assistant or shop that made the piece originally, the difference between the original and copy is that the new work lacks whatever changes time may have wrought on its physical materials, as well as whatever aura attends to the artist’s authorization. Is such an aura akin to that of saints’ relics? Can non-believers dispense with the issue? Is it only a problem for the market?

Other cultures have different standards of authenticity. The wood in medieval Japanese temples has been continuously replaced throughout the centuries. The Japanese also accord authentic status to ancient swords, whose handles have been replaced, as well as their blades–based on the premise of authentic continuity of attribution. But the West is thoroughly materialist about such things. A Western curator would certainly prefer a handle-less sword to one with a more modern handle. Artists have changed the rules, and the rest of us have yet to catch up.

I have long thought that with many installations, and much three-dimensional artwork involving video and now digital technology, we will have to move from the traditional standards of the art world to those of the performing arts, so that each presentation is as close to the original as possible–assuming the minimal curatorial interpretation–with the understanding that components inevitably change. Some work will not age and evolve as well as others. How can one exhibit Nam June Paik’s “Magnet TV” with digital television equipment instead of a vacuum tube?

We have come to a more nuanced understanding of “authenticity” in regard to earlier art, where the hands of multiple executants were assumed as part of studio practice. We now have to face the question of originality for artwork that was never intended to sit or hang quietly in galleries. But such a change in standards is one that can only be accomplished by consensus of numerous groups and a large population of artists, museum professionals, academics, collectors, dealers, and the general public. It will take time, and cause a lot of argument and pain. But consensus will only come about if the topic is out in the open, and presented as the as-yet unanswered question that it is today.