[Evan travels to Japan, and takes us with him, discussing culture shock, overwhelming visuals, and what it’s like to be a “gaijin“. — the Artblog editors]

Japan, like any other country, has its share of contradictions embedded in the fabric of everyday life–the clash of old and new in its architecture, or the impulse toward both secrecy and openness in its people, for example. And as a foreigner (gaijin) visiting my sister and traveling from Tokyo to Miyazaki City, I experienced those contradictions firsthand, feeling, by turns, both incredibly welcomed and politely excluded by the people I encountered. Despite this, my three weeks in Japan were excellent and exhausting; I fell deeply and excitedly in love with the place and the people, and became particularly fascinated with the richly layered and diverse visual culture that has developed on the streets of the country.

Visually overwhelmed in Tokyo

Asakusa, an old district in Tokyo, was my home for the first few days of the trip. A magnificent Buddhist temple, Senso-Ji, stands at the heart of the district, the air incense-soaked and humid. I marvelled at the long rows of shops that led up to the temple’s main entrance on both sides of a pedestrian walkway. By nightfall they had all closed, but each had an intricate, earnestly executed mural of everyday and festival scenes on its metal facades, taking every opportunity to make the mundane meaningful, and making the stroll to Senso-Ji’s monumental gates seem like being between two giant, slow-moving strips of film.

Smoke wafted from the still-smoldering megalithic incense holder and filled my nose and lungs; I washed my hands and face and drank from the water coming out of the mouth of a brass dragon in the holy trough beside it. I did not just see this place, but covered and filled myself with it, marveling at the temple’s monumental red-and-gold main structure, with a roof as large and sloping as a small mountain, and the countless precious adornments and trinkets in its inner hall, half-concealed by ancient doors of thick, weathered dark wood.

Language barriers mean chef’s choice

For dinner, I had sushi, but not the kind one expects in the States. I took a chance and entered a small restaurant on the corner of a side street, intrigued by soft, glowing light radiating from paper window screens and a welcoming, traditional dyed curtain over the door, glowing a gentle lime green in the light of hanging lanterns. The quietly diligent chefs and bar filled with regulars did a double take as my family and I entered; they shuffled at marvelous speed to accommodate us.

Many hilarious attempts at conversation ensued. There were no California rolls here, no rolls of any kind–and no menu or prices either. There were simply the most delectable and marbled cuts of fish perched masterfully above a dab of fresh wasabi and plump white rice–squid, red snapper, octopus, and tuna took the main stage, supported by a few remarkable small dishes. Whole charred prawns, still staring with glassy black eyes and with delightfully crunchy exoskeletons, were a highlight, as was our first dish: a small mound of seaweed strands thinner than angel-hair pasta, with a gelatinous texture, topped by miniscule peppers and bamboo shoots. My sister was able to navigate much of the the ordering process with the Japanese she knew, but as was the case at many restaurants, we resigned to letting the chefs bring us what they chose.

One of the principle joys of eating in Japan is the simplicity of the cuisine, both in taste and appearance, and the care that is taken to extract the basic perfection of every ingredient. I felt as though my taste buds were slowly being unlatched from years of American eating and its overworked and over-indulgent tendencies. Our exit from the establishment was met with vocal and heartfelt thanks and well-wishing, followed by startlingly acrobatic, full 90-degree bows from the old chefs–I am sure their smiles lingered as long as mine.

After dinner, I wandered labyrinthian alleyways filled with open-air bars–watering holes for evening libation–with neon signs forming their own surreal landscapes of kanji (traditional Japanese characters derived from Chinese) above communal tables packed with locals using their drinks as an excuse to finally break from their societal standards of behavior. Here, I spent the rest of the evening attempting to order beverages with my (still-broken) Japanese, and trying to act natural while receiving nervous and intrigued glances. I was clearly the talk of the block, my sake slowly rounding off the hard edges of a long day of travel. For a city so filled with foreigners, it seemed as though I was the first they had seen in ages. I still wonder how many pictures there are of myself online with the caption “Gaijin in Asakusa!!” that I will never see.

Kyoto contrasts

Kyoto was the next city I visited–a place where entire neighborhoods seem still locked somewhere in the past, with the same stone path beneath our feet and the same aged wood of the guest houses (ryokans) that dignitaries and lords experienced a century ago. Gion, the most famous part of town, is comprised of the geisha district, the newer red-light district, and the surrounding temples and streets. I felt the thick and ancient mystery of old Gion seeping from each of its shuttered inns and bars as I peered through gaps in wooden window slots for a glimpse inside, exploring as discreetly as possible so not to disturb what felt like the well-rehearsed meditation of a neighborhood resilient to the passing years.

There is a stark duality when crossing from old Gion to new Gion, parts of the neighborhood separated by the main street. The poised calm of the old district is dissolved in a matter of seconds as newer concrete high-rises shoot up from the ground. I marveled at the sheer number of “entertainment” bars. Alone and a man, I was an easy target for solicitors inviting me to indulge in their services. I politely refused each one, unsure of whether I was in fact putting myself at risk of getting in trouble as I went deeper and deeper into the alleys of the buzzing red-light district (a place frequented by the Yakuza, or Japanese mafia), playing “dumb gaijin” when receiving concerned looks from sharply dressed and imposing men guarding shuttered ryokans.

I turned down one particularly thin and winding street, and was abruptly greeted by four beautiful women in perfectly put-together kimono, standing upright and in line, their unnaturally high-pitched voices in unison: “Kon ban wa!” (“Good evening”). A few steps closer, realizing that I was a gaijin and clearly not partaking of their services, they scurried back into their guesthouse before I could muster a response, disappearing into thin air in less time than it took me to release the shutter of my camera.

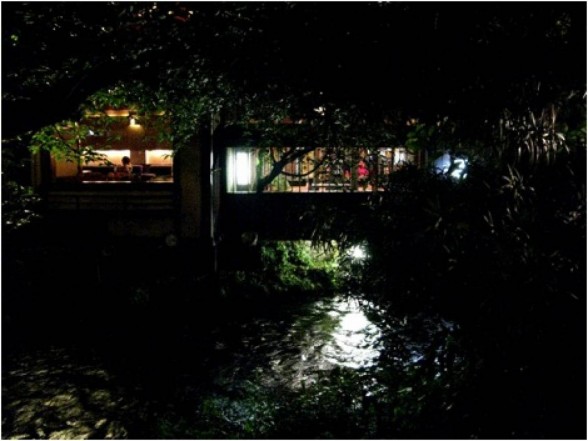

Feeling the need to escape from the solicitors and rest my feet, I entered a small bar overlooking the canal that runs through new Gion, choosing it because it clearly advertised having a menu in English…something I generally tried to avoid, as it often means more foreigners. But this time, I couldn’t resist. I ordered a sake (or nihonshu) and looked out over the canal, reflections of the lanterns above dancing on the water.

I told the bartender and locals at the bar that I was American, and from New York–to build anything resembling a conversation, you occasionally need to forget your homegrown reluctance and become the stereotypical description of an American, responding with a thumbs-up and a heartfelt “Oh, yes!” when confronted with badly pronounced attempts at saying “Statue of Liberty?” and “Central Park?” I honestly couldn’t do much better myself, and with locals this friendly, I was more than happy to play the part. I laughed about it under my breath as I walked back to Artspace Yosuga, the bar/cafe/gallery/artist residency program where we were generously allowed to stay during our time in Kyoto.

Run by a retired police detective and his partner, Artspace Yosuga sits in an unassuming, two-story traditional house nestled off Shijo-Dori, a 20-minute walk west from Gion. On our third night there, our hosts threw us a welcome party and invited local artists and friends to the intimate sake bar, where we sipped delectable local and hard-to-find varieties, laughing into the early hours of the morning with an eclectic mix of painters, architects, engineers, professors, and students. This was most welcoming and embracing group to share our company, and the glimpse we were given into their true lives made a tearful goodbye even more bittersweet.

Osaka, raw and unfiltered

I entered Osaka in a meditative state after a stay at a Buddhist monastery in the mountains of Koyasan, and was promptly plucked from this ease into the Naniwa ward, feeling more like an extra on the set of “Blade Runner” than a tourist. Osaka felt like the first unedited city that I saw in Japan, as if the people there had become too tired holding up the veil of perfection and tradition that places like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Nara use to hide their troubles. I saw groups of teenagers skateboarding on the sidewalks; businessmen passed out on park benches in their expensive suits, still clutching bottles of whiskey bought at the convenience store; the streets were unnaturally bright and washed out from towers of neon that made Asakusa seem like a mere strand of Christmas lights. Osaka was imperfect, yes, but more than anything, it was absolutely human.

A calm canal cuts Naniwa in half, cables of hanging lanterns offering a warmer source of light–the analog predecessor to the fluorescent advertisements on either side of the lapping water. Enter into the vast red-light district, and the glowing food menus are replaced with billboards advertising headshots of all the men and women available for your “entertainment,” should you choose to indulge. Even as Osaka holds the honor of being the “nightlife capital of Japan,” the irony of this title emerges after 11 pm on a Friday, when almost everything shuts down as if it were a sleepy Monday.

I saw one bar with lights still on, and I hadn’t even stuck my head in for five seconds before a hyper-fidgety host rushed us in and sat us down–we had found ourselves in a place called “Sex Machine,” a not-quite-dive bar completely dedicated to James Brown and his heritage…earnest but misguided, its walls were covered with paintings of stereotypical African animals and people (utterly cringeworthy); a framed picture of the owner of the bar holding a poster of James Brown and standing next to James Brown; and a dancing and singing James Brown doll, with which we would reluctantly end up posing for pictures with the bar owners. Clearly drunker than us, they hopped and danced and sang when “Get on Up” finally came through the speakers. My sister and I half-joined in while exchanging looks, wide-eyed and eyes watering with tears of laughter–as if to say, “Oh my God, where have we found ourselves this time?” a question that would become the anthem of this adventure.

Like so many good things, this adventure eventually came to an end. I must inevitably return to Japan, as these three weeks felt like minutes upon boarding the plane home. Next time, I will give Kyoto and Osaka the time they deserve, so I can unravel their mysteries and intricacies even further.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a recent graduate of Tyler School of Art.