[Marvin reviews a show of printmaking and collage work that both achieves a breadth of artistic approaches, and captures the artists’ personal takes on the theme of “memory”. — the Artblog editors]

As a young print enthusiast, it is always my pleasure to stumble across a show dedicated to the medium. Renderings: New Narratives and Reinterpretations, on view in the Mechanical Hall Gallery at the University of Delaware, is a perfect example of an exhibition that highlights works from a recognized collection and brings to light new scholarship in the printmaking field.

Repeat, rework, reprint

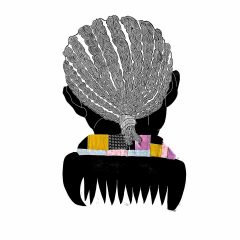

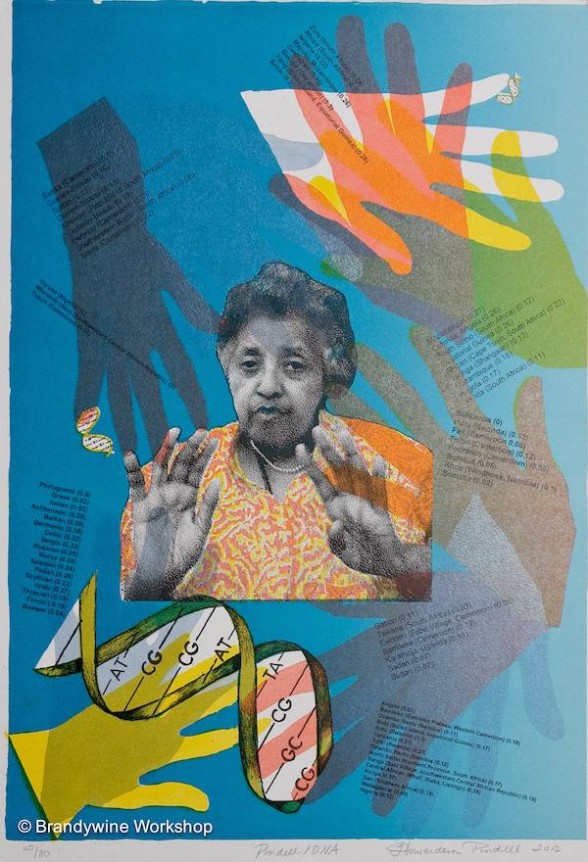

Drawn from the Philadelphia-based Brandywine Workshop, Renderings examines contemporary prints produced by artists from the African-American and African diaspora. At the core of Renderings is the idea that printmaking is possibly the most transparent of all the artistic practices for these artists to convey the theme of memory, an important theme used to connect with and visualize the past. Each print is composed of carefully selected images, often combined with text, evoking resilience, remembrance, personal and social histories. Some prints appear as collages of pasted clippings from ephemeral materials. Printmaking allows the artists to constantly repeat, rework, and reprint an image that creates an ever more powerful message.

The exhibit is organized by curator Cheryl Finley, associate professor of art history and Director of Visual Studies at Cornell University. All the featured artists participated in the Visiting Artist in Residence program at Brandywine. Some of the works presented are products of the artists’ first-time experiences with printmaking.

Unique yet unifying stories

As a whole, the works create a systematic, visual narrative throughout the three-room gallery. At first glance, several of these collaged surfaces may look packed with disparate subjects. However, a deeper look allows viewers to fully appreciate both the artist’s mastery of the print and the art of storytelling–a key practice within the art of the African-American and African diaspora.

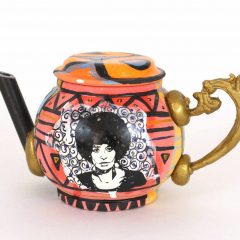

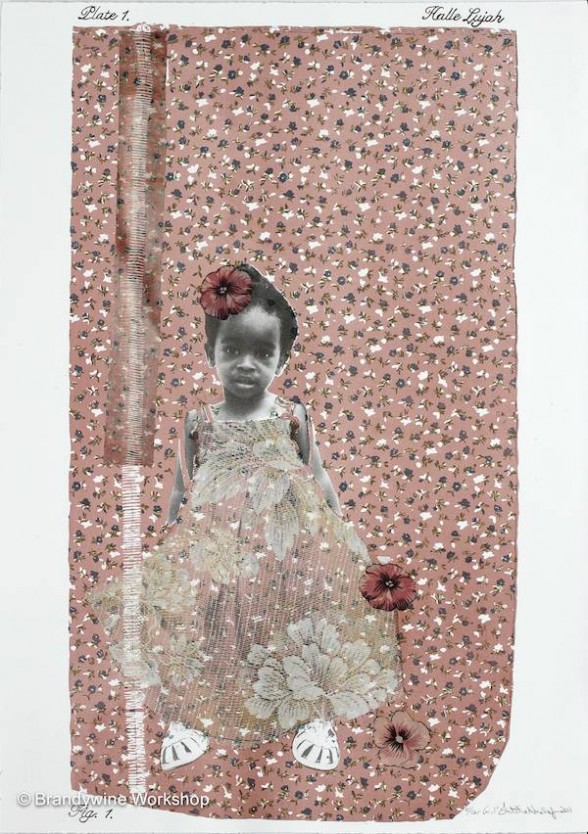

While many of the works share similar motifs (personal photographs, references to slavery, racial struggles), each portrays a unique story. Several artists incorporate personal photographs that contribute to the dialogue. Letitia Huckaby’s “Halle Lujah (Flour Girl)” combines a photograph of the artist’s daughter with lace and cord appliqué set on a manufacturer’s printed drawing of an authentic flour sackcloth; the pattern-like composition pays homage to the artist’s ancestral ties to quilt- and craft-making.

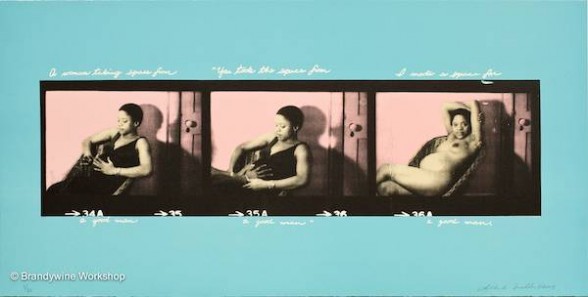

In “I Made a Space for a Good Man,” Deborah Willis creates a triptych-like lithograph using three photographs of herself during her pregnancy with her son, the artist Hank Willis Thomas (also featured in this show). In an accompanying wall label, we are given insight on the title’s meaning. As a black, female undergraduate student at the Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts), Willis was called out by a professor for “taking up a good man’s space,” since she would eventually get married and have children. Interestingly, many of the female artists here use their own intimate portraits, thus inviting viewers to contemplate them at their lives’ most vulnerable moments.

References to the slave trade

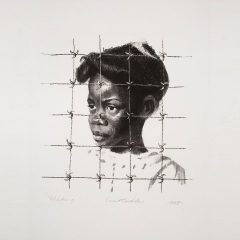

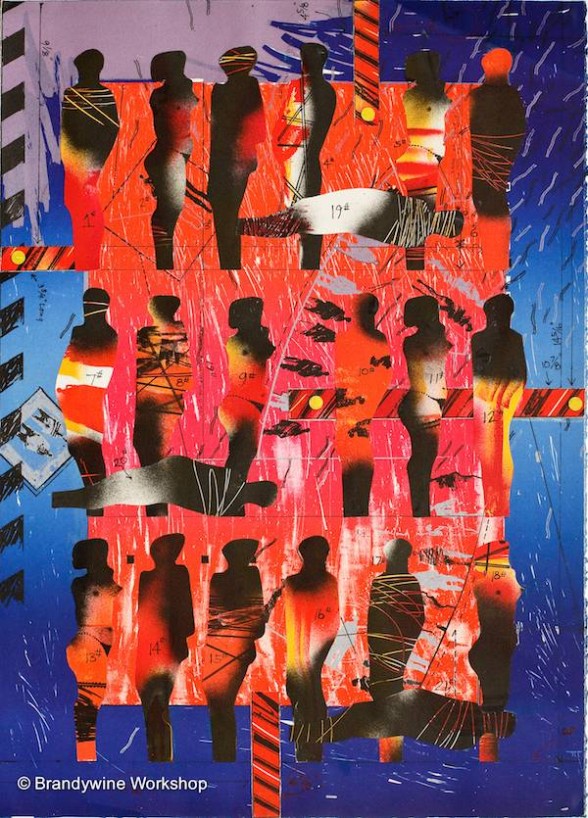

Other pieces in the exhibition make subtle or explicit references to the Transatlantic African slave trade and the road to freedom from slavery. In “Blues for the Middle Passage II,” John T. Scott alludes to the Middle Passage–the transport of African captives, as cargo, across the Atlantic. The silhouetted figures remain anonymous, save for the unique number inscribed on each one.

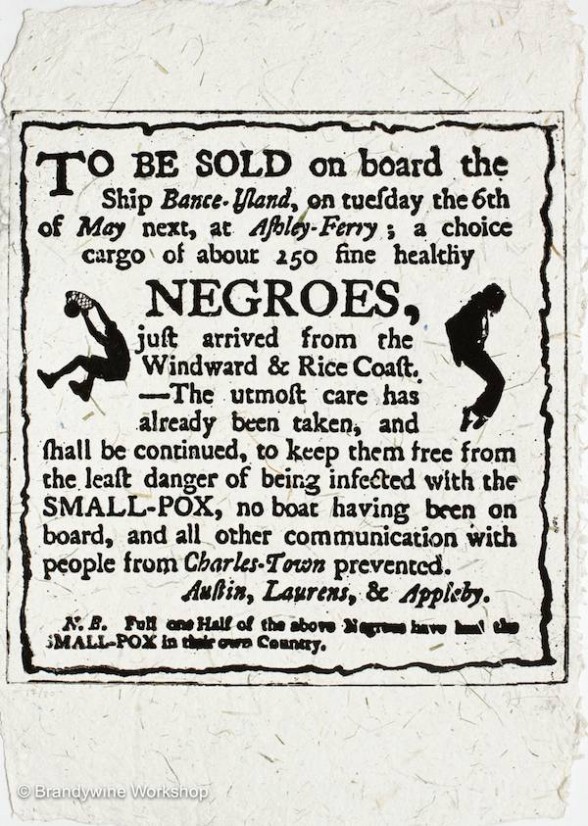

Hank Willis Thomas’s metaphorical “Negroes to Be Sold” parallels 18th-century slave advertisements, yet he uses the silhouetted figures of Michael Jordan and Michael Jackson (who are presumably victims of being in the limelight).

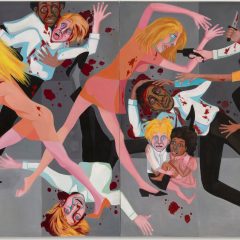

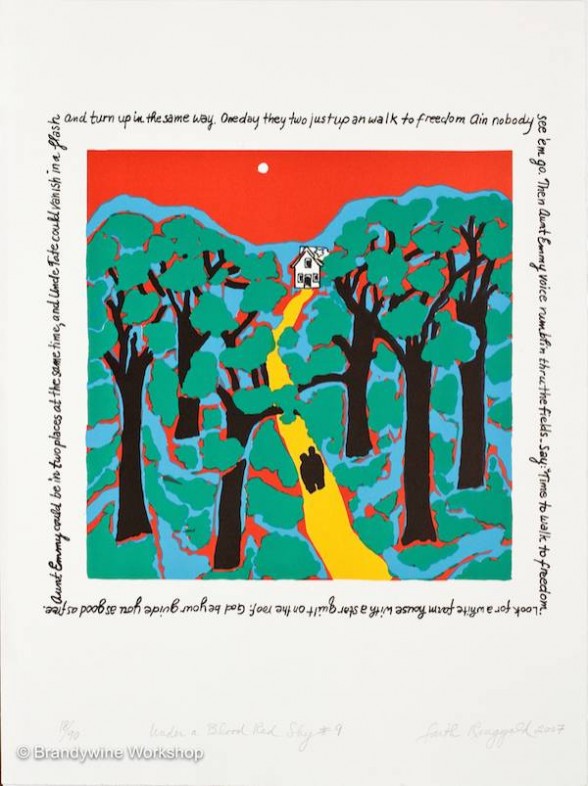

Also a metaphorical nod to slavery, Faith Ringgold’s “Under a Blood Red Sky #9,” which appears like a page from a children’s storybook, is a haunting reminder of the dangerous journey upon which many runaways embarked.

An accomplished show with wide appeal

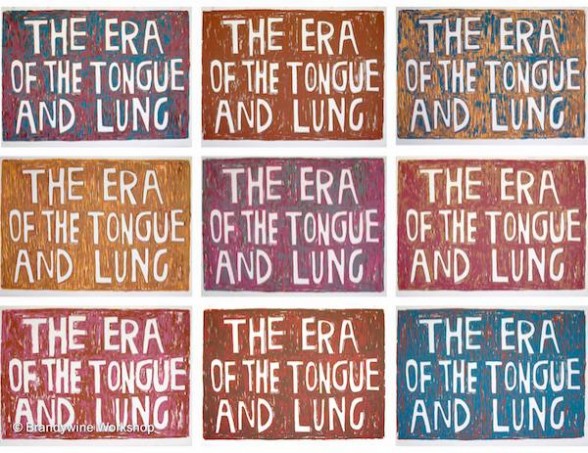

The largest work is Ayanah Moor’s “The Era of the Tongue and Lung,” an installation of nine colorful screenprints composed of the same phrase taken from an essay by Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston. The screenprints can be viewed as modern-day protest signs resembling those used during the Civil Rights era.

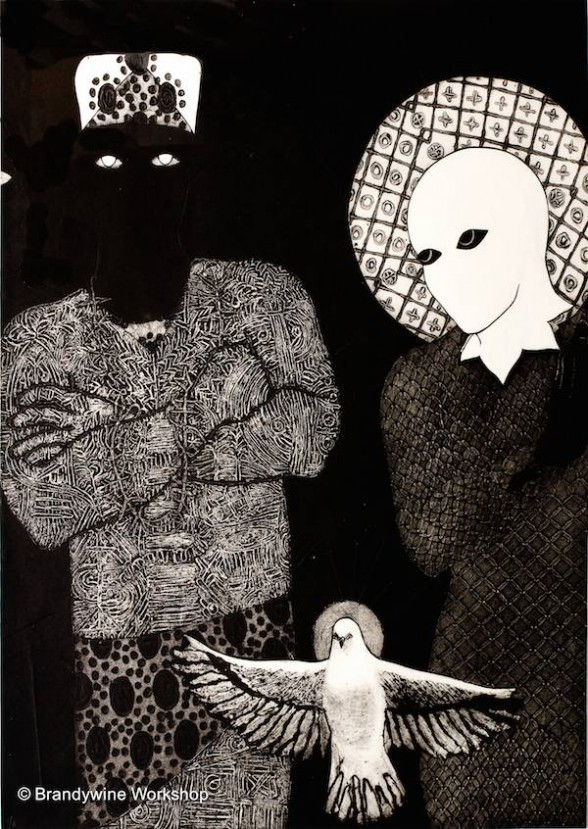

Finley also includes prints from the Afro-Cuban diaspora. The most impressive are the collagraphs–an often-overlooked method–by Belkis Ayón. In collagraphy, the artist adheres different materials (Ayón used cardboard and paper) onto the plate, creating a textured surface with different tones. Ayón’s collagraphs represent her fascination with three things: the Abakuá all-male secret society, mystical iconography, and feminist aesthetics. As much as Ayón had an impact on contemporary printmaking, this artist deserves more scholarship on her short life.

Renderings is an exhibition that embodies everything that the Brandywine Workshop has aspired to fulfill since it was launched in 1972 by Allan L. Edmunds and other African-American artists. Brandywine serves as a meeting place where multi-ethnic artists can share their personal stories through artistic expression. Although this show discusses the African-American and African diaspora, it should have wide appeal because of the world-class artists it features, and because its imagery is well-executed, thought-provoking, and bold. In fact, Renderings raises issues of race, gender, tradition, and history, all of which are powerful themes to engage many different audiences.

What is important in the show is the ubiquitous presence of memory and identity in each of these prints. While looking at the works, a viewer cannot stop wondering about their own past–where their genealogy began. Triggering that personal reflection is a goal of most exhibitions, and one this exhibition achieves.

Renderings: New Narratives and Reinterpretations at Mechanical Hall Gallery, University of Delaware runs through Dec. 7, 2014. 30 North College Ave., Newark, DE 19716.

Concurrently on view is Visual Narratives: Prints from the Brandywine Workshop & Archives at Art Gallery at City Hall, now through Jan. 23, 2015, City Hall, Room 116, Philadelphia, PA 19107.

Marvin Aguilar recently relocated to Philadelphia from Miami, Florida, where he worked as a freelance art and architecture writer and independent curator. Marvin studied art history at Georgetown University, where he also rowed on the Men’s Varsity Lightweight Crew Team. Currently, he’s pursuing a master’s in education at Saint Joseph’s University, as well as coaching high school crew on the Schuylkill River.