[Michael follows artist and environmentalist Mary Mattingly and several co-collaborators into an exploration of self-sufficiency on the Delaware River. — the Artblog editors]

In the midst of winter’s premature darkness last month, the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education presented a lecture and panel discussion about Mary Mattingly’s environmental artwork. The Center, at the heart of 340 acres of woodlands, meadows, and wetlands, and hidden within the city limits in Roxborough, just off Ridge Ave., was the perfect stage for Mattingly’s talk on her WetLand project, a floating boat sculpture that explores the degradation of fragile ecosystems and the lasting impacts of the privatization of water.

Mattingly’s talk on Jan. 28, 2014, the fourth annual Richard L. James Lecture, was titled “Environmental Art for a Changing Planet,” and discussed her contributions to and the planning behind her project, WetLand. The piece is a self-sustaining ecosystem made of recycled materials resembling a house that fell out of the sky and was left afloat the Delaware River, anchored at the Independence Seaport Museum. If you were near Penn’s Landing during the 2014 Fringe Festival, you might have seen WetLand floating off Philadelphia’s shores.

Tracking environmental change

After traversing the winding dirt road that leads to the Schuylkill Center, I was warmly greeted with a cup of coffee, compliments of the Center, and joined the packed lecture hall for a brief introduction to the lecture by Christina Catanese, current Director of Environmental Art.

Following her introduction, Mary Mattingly traced the highlights of her oeuvre in a slide lecture, beginning with her childhood in Rockville, Connecticut, a town that the artist noted is a victim of DDT buildup from pesticide use before DDT’s ban in 1972. The impacts of pesticide use affected native species and marred ecosystems–a concern of Mattingly’s that developed into a desire to inspire environmental change with her artwork.

Around the millennium, Mattingly moved to the Southwest. There, she began photographing landscapes in a series that scrutinizes the privatization of bottled water and the resulting consumer demand for it. A new sector of industry emerged– bottling, marketing, and sales of bottled water–and grew exponentially as demand increased. Today, the bottled water industry acts as an arbitrary middleman for this natural resource, essential for human life; we are often dependent upon this middleman when purchasing water from a store or at a water filling station, like the one in Arizona that Mattingly photographed.

Reclaiming water

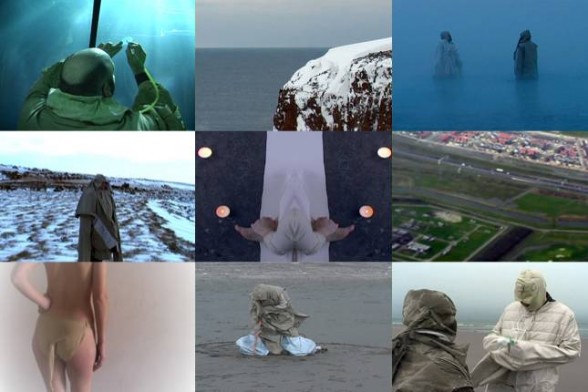

Other photos from the Southwest water series feature eco-art Mattingly produced, such as her fantastical water purification body suits, which attempt to create small-scale, self-sustaining water purification systems for the individuals who wear them.

Following the artist’s initial investigations into water, she created WetLand’s predecessor, the Waterpod Project (2006-2010), a sustainable, livable environment aboard a barge that traveled throughout the five boroughs of New York City. When discussing Waterpod, she likened the vessel to a biosphere that grew out of her interest in removing herself from the extensive supply and demand chain created by water privatization; the reliance upon grocery stores for sustenance; municipal waste management, and electricity consumption.

Mattingly and her collaborators invited the public aboard their floating home for educational programming about water recycling and community gardening throughout the entirety of the Waterpod Project. Because the project is educational at its core, they even collaborated with local high school and college students for the conception and construction of the vessel.

Stepping further from the system

WetLand is Mattingly’s most recent collaboration as a part of the 2014 Fringe Festival in Philadelphia. It functioned as an eight-week long performance aboard the ship by the artist and 13 other resident collaborators–Rebecca Aston, Ellie Clark, Jon Cohrs, Anna Ekros, Ivan Gilbert, Abby Holtzman, Brian House, Kim Reid Kuhn, Greg Linquist, Saito Group, Esteban Gaspar Silva, Karla Stingerstein, and Rand Weeks.

WetLand is now permanently docked at the Independence Seaport Museum on Penn’s Landing. During the 2014 Fringe Festival, the floating eco-lab was home to chickens, bees, and floating vegetable gardens anchored at the ship; these were used to source, with the assistance of Greensgrow Farms, a meal during the opening event.

Beyond functioning as a self-sustaining craft for Mattingly and her collaborators, WetLand is a living, breathing sculpture that grows with each event and visitor to grace its deck. WetLand’s ecosystem features water filtration, a dry compost system, a composting toilet, vegetable gardens, and indoor hydroponic gardens. The floating residence is powered by solar panels for electricity and water is sourced from a rainfall collection and purification system. Together, these systems allow for life on the ship.

Future collaborators and the ever-changing environment on the Delaware River will further contribute to the developing history of WetLand. Although the space is now maintained at the Independence Seaport Museum awaiting new inhabitants, Mattingly was one of the first to live on the vessel for 6 weeks during the 2014 Fringe Festival. The Penn Program in the Environmental Humanities, the PPEH Lab, has paired with the artist to maintain WetLand and organize the future fellows who will contribute to the ecosystem.

Panel discussion on environmental art

After the lecture, there was a brief panel discussion about the history of environmental art and its role in contemporary society. The artist was accompanied by Mary Salvante, founder of the Environmental Art Department at the Schuylkill Center and the current Gallery and Exhibitions program director at Rowan University; Maya van Rossum, Delaware Riverkeeper, who leads the Delaware Riverkeeper Network; and Bethany Wiggin, director of the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities and associate professor of German at the University of Pennsylvania.

The discussion began with Mary Salvante’s mention of what she calls “eco-ventions,” like WetLand, and their effectiveness as an educational resource. Mattingly’s living sculpture immerses individuals within a utopic fantasy where life can be sustained without recourse to grocery stores, gas stations, and Starbucks. This fantasy is set against the Philadelphia skyline in an attempt to ground the events held aboard WetLand in reality.

Bethany Wiggin noted Mattingly’s ability to scale down the components of an unfathomable global process–the supply-and-demand chain–into a self-sufficient procedure that is observable on a micro-scale. She effectively simplifies the large-scale collection of food, water, energy, and waste, a process that typically involves multiple money-hungry corporations, and condenses it atop one boat.

The project is an example of the positive change that can stem from educational resources and a working demonstration of a completely self-sustaining ecological system that could be a functional form of advocacy for sustainability issues in the future.

The four panelists concurred that the appeal of WetLand is large in scope. The events that took place there, like the meal and performances, informed a wide range of people that may have otherwise overlooked environmental concerns. WetLand’s fantastical design attracts viewers into an educational storehouse of information, available on-site and online, on reducing waste and alternative ways of obtaining the foods we consume. In doing so, Mattingly has laid the foundation for a budding experiment on the banks of the Delaware River in Philadelphia.

WetLand is temporarily closed during the winter season, but they expect to post their future hours soon. For more information on future collaborators, or if you would like to get involved with WetLand, visit PPEH Lab.

Enviromental Art for a Changing Planet featured artist Mary Mattingly on Jan. 28, 2014, commemorating the fourth annual Richard L. James Lecture at the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education.