[Noreen comes face-to-face with feminist art’s progress, or potential progress, at an installation in Canada. — the Artblog editors]

This month, I paid my first visit to Montreal, the largest city in the Canadian province of Quebec. The city is home to approximately 1.6 million people, mostly French-speaking, yet many of its residents come from Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, China, and other countries. I decided to pay a visit to a gallery in East Montreal, which hosted Face, an installation by Korean-born artist Insoon Ha. In light of the city’s cultural patchwork, both the installation–deeply embedded in racial and feminist issues–and the Montreal experience helped me investigate what it means to make and practice contemporary feminist art.

A simple exercise of erasure

My stay at a low-cost hostel in the heart of the city brought me into close quarters with travelers from all over the world. In the evenings, dinner conversations were colored by Algerian, Indian, French, and Argentinian accents—yet all were welcomed, heard, and understood.

Located on the bustling Boulevard Saint Laurent, LA CENTRALE Galerie Powerhouse hosted Ha’s installation. Until May 15, the work occupied the generously-sized storefront space. The installation’s main feature was the tiling of large-scale, digital self-portraits adhered loosely to the floor, echoing Ha’s face from wall to wall. To view the work was to destroy it–in order to enter the gallery space, I had no choice but to step on the self-portrait of the artist.

Coupled with the physical media was the artist’s performance. The more gallery patrons who entered the space, the more destruction the portraits endured. Using a simple ceramic bowl of water and a washcloth, Ha repeatedly cleansed the portraits of dirt and debris tracked in by the viewers’ shoes, but the effort was clearly futile–the portraits sustained irreversible damage.

Face feels familiar

After I experienced Face and read more about Ha’s work, I found that the destruction of her self-portraits undeniably tied itself to cultural and feminist issues. Her sculpture and installation specifically center themselves on the oppression of Korean women. In the terror of World War II, many young Korean women were abducted and forced into sex work, often sold as “comfort women” to Japanese soldiers. The viewers of Face, stepping upon the countless faces of the Korean artist, represent the abuse and destruction of identity that comfort women suffered. The artist’s woman-based narrative is one that openly addresses and examines sexual and racial violence and oppression–a point that most, if not all, contemporary feminists identify as an essential component of feminist art.

Though Face addresses such third-wave components through a specific perspective–that of a Korean woman’s–the art itself seems rather stagnant. Although the focus on a non-white female perspective characterizes third-wave (or contemporary) feminism, and unites Face under this construct, the concept of the work is not entirely new. Ha’s constructed interaction between viewer and artist bears strong resemblance to iconic works of the ‘60s and ‘70s, which are often tied to second-wave feminism and feminist art.

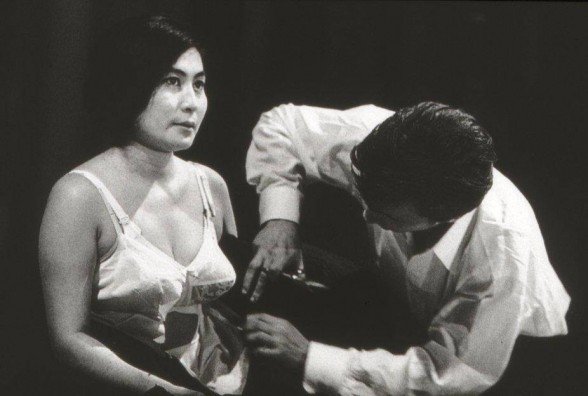

One such example is Yoko Ono’s 1964 “Cut Piece,” in which each viewer was directed to cut away one piece of the artist’s clothing. Later, Marina Abramovic amplified such a relationship between artist and participant in her 1974 performance “Rhythm 0”. Directed by a gallery sign, audience members chose from 72 objects to use as they pleased in the performance, resulting in the cutting away of Abramovic’s clothes and the sticking of rose thorns into her stomach. One participant chose to aim a loaded gun at her, and another pushed it away.

In comparison, the artist-participant relationship of Ha’s Face falls flat. Ono’s and Abramovic’s then-revolutionary performances are now over 40 years old, and the tired replay of such works robbed Face of the edge it needed to resonate beyond the gallery. The pre-mandated destruction between viewer and object also drained the work of vitality and activity. In viewing the piece, I asked myself, What comes of the work’s destruction other than emotional resonance? What sort of new critical discussion does the work provoke? Could the work bring about sociocultural change?

To me, Face failed to provide an answer to these questions, or even stir a dialogue about them. In the nearly empty space of the gallery, there was almost no conversation to begin with. The enclosed spaces of galleries and museums rarely attract the audience needed for lively discussion, let alone one passionate enough to bring about change.

Not only are museums, galleries, and other sterile institutions often inaccessible to the poor, homeless, and the socially marginalized, they do not attract the general public outside of the arts community. I often wonder: Does art need to be bigger, louder, and flashier to attract a wider audience? Some contemporary artists have followed this notion, using the spectacle of grandeur to their advantage.

Moving beyond the echo chamber

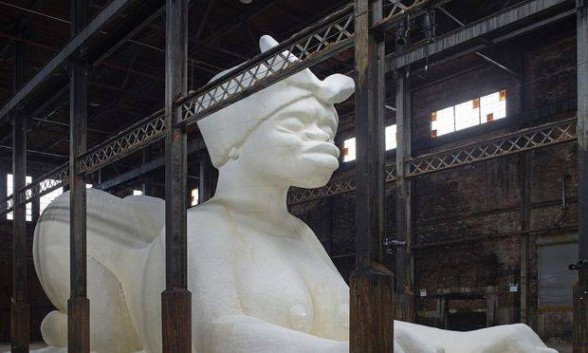

Take, for example, Kara Walker’s recent public project, “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby”. In the now-demolished Domino Sugar factory in Brooklyn, Walker and an expansive technical team erected an enormous sphinx made of sugar, with the face and features of a hypersexualized black woman. The 35-foot-tall statue–especially its 10-foot-tall rendition of labia–quickly gathered social media attention, amassing Instagram photos, Tweets, hashtags, selfies, and all.

A grand-scale piece like this certainly spurred a discussion (as the artist intended) about the relationship between black women and U.S. history. With “A Subtlety,” Walker opened a proverbial can of worms about race, gender, sexuality, slavery, and abuse: topics that are highly relevant in the narrative of contemporary women’s art and black feminism. Most importantly, the discussion survived long after the piece closed to the public–thanks to the persistence of social media, and its users’ affinity for selfies in front of art.

Enabled by this virtually global open forum, Walker’s work has continued to resonate throughout the Internet, encouraging discussion of important issues in the lives of black women in America. With this in mind, why should contemporary artists ignore the relationship between art and social media? On Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, or YouTube, any artist’s work has the potential to be accessed worldwide–even those artists whose voices the ableist, classist, racist, and sexist institutions of the contemporary art world refuse to hear.

While I do not envision the use of social media as a direct solution to social issues, its power lies in its accessibility and openness. Uninhibited by the boundaries of institutional discrimination, which stifle social change by perpetuation of their own values and exclusion of others, social media has the potential to open a worldwide forum of discussion. With this comes the chance for global conversation and exchange, which feminist art should use to dismantle the social boundaries and oppressive standards built by discriminatory systems. In other words, social media is a podium with the ability to reach the world at large. It is time for feminist art to take its place at the microphone.

Face by Insoon Ha was on display at La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse, 4296 St-Laurent Boulevard,

Montréal, Québec H2W 1Z3, Canada, from April 17 – May 15, 2015.