We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s at the Woodmere Art Museum through Jan. 24, 2016 is an important realization of the Woodmere’s mission to tell the story of artists in the Philadelphia area. The exhibition is a fascinating survey of an entire community—one that created its own artistic institutions in the face of neglect, if not outright exclusion by the mainstream Philadelphia art world. The project grew out of a series of conversations between the curators—Susanna W. Gold, Rachel McCay, and the museum’s director, William R. Valerio—and participants; 13 of them are transcribed in the catalog (ISBN 978-1-888008-5), making it an essential complement to the exhibition. Among those interviewed were artists and their heirs, collectors, teachers, and other arts professionals. They were able to re-insert important figures into a history that has never been completely documented. A number of videos, playable on small monitors in the gallery and available on the museum’s website, offer still further information.

Search for African visual traditions

A small gallery sets the stage and introduces several themes with works that occasionally pre-date the given timeframe. The cultural history behind the art on view begins in the 1920s with the New Negro Movement, whose champion, Alain Locke, was a native Philadelphian. The movement’s search for African visual traditions is represented by the polychrome maquette for “Ethiopia Awakening” (1914) by the Philadelphia-educated artist Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller. The sculpture’s tightly bound legs and the drape covering her head reflect knowledge of Egyptian burial customs, even though Fuller was working prior to the worldwide Egyptomania that followed the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Nearby is Barbara Chase-Riboud’s stunning, wall-hung sculpture in aluminum and silk, “Time Womb” (1970), emphasizing the curators’ interest in including women in the exhibition, as they often faced a double prejudice as artists. “Time Womb” is a study in contrasts, an upper part in metal from which hangs a knotted skein of silk, a slender form in pale, glistening colors that nevertheless conveys strength and agency; the crumpled aluminum suggests a fist about to open.

Another predecessor whose work and example were crucial to many of the artists in the exhibition is Henry Ossawa Tanner, with “Study for Christ” (1900), a black chalk drawing of a bearded model, stripped to the waist. Tanner’s career was eased by the fact that he spent most of his working life in France, where his race was not an impediment to his success. The drawing represents another theme that runs throughout the exhibition: the representation of black identity through images of the black, male body. In addition to the Tanner, this is powerfully introduced in the first gallery with Barkley Hendricks’ “J.S.B. III” (1968)—a portrait of James Brantley, an artist whose own portrait of a young man, “Clarence Morgan” (1972), was one of the paintings I was happy to discover.

Community support

Black artists were supported by a number of crucial institutions, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Fine Print Workshop, Alfred Barnes and the Barnes Foundation, and The Pyramid Club. Although the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (PAFA) was one of a handful of American art schools that admitted black artists as early as the 19th century, it was only at the end of the period covered by the exhibition that increasing support for black faculty at the mainstream art schools—PAFA, Tyler, and University of the Arts—created expanded opportunities for significant numbers of black students.

Various community-based organizations offered employment and facilities to black artists, including the public schools and groups such as the Ile Ife Black Humanitarian Center, the Wharton Centre, and the Green Street Workshop, all supported by the federally-funded Model Cities Program during the ’60s-’70s. Many of the artists crucially functioned as mentors for the next generation. Numerous interviewees mentioned the importance of Charles Pridgen as a particularly generous mentor; his most important painting, “The Blues” (c. 1950), is a standout, exhibited along with a graphite study for the painting.

New discoveries even for seasoned viewers

The exhibition was organized around an artistic community rather than a style or subject, so it is not surprising that the works do not necessarily address one another. Instead they present an opportunity to view a broad range of strong artworks that will include unknown discoveries for many visitors—such as myself—and a welcome, renewed acquaintance for insiders of this community. While a number of works are owned by the Woodmere and by other Philadelphia institutions, many are in private collections, therefore not generally accessible. There is a good selection of prints, some of which are products of the WPA, others printed in the Brandywine Workshop, another institution important to this community. I was particularly impressed by the lithographs of Raymond Steth, such as “Evolution of Swing” and “Beacons of Defense” (c.1942); they reveal an almost cinematic ability to combine crowds of figures in complex, narrative subjects within clear compositions. They would certainly have scaled up to become successful murals.

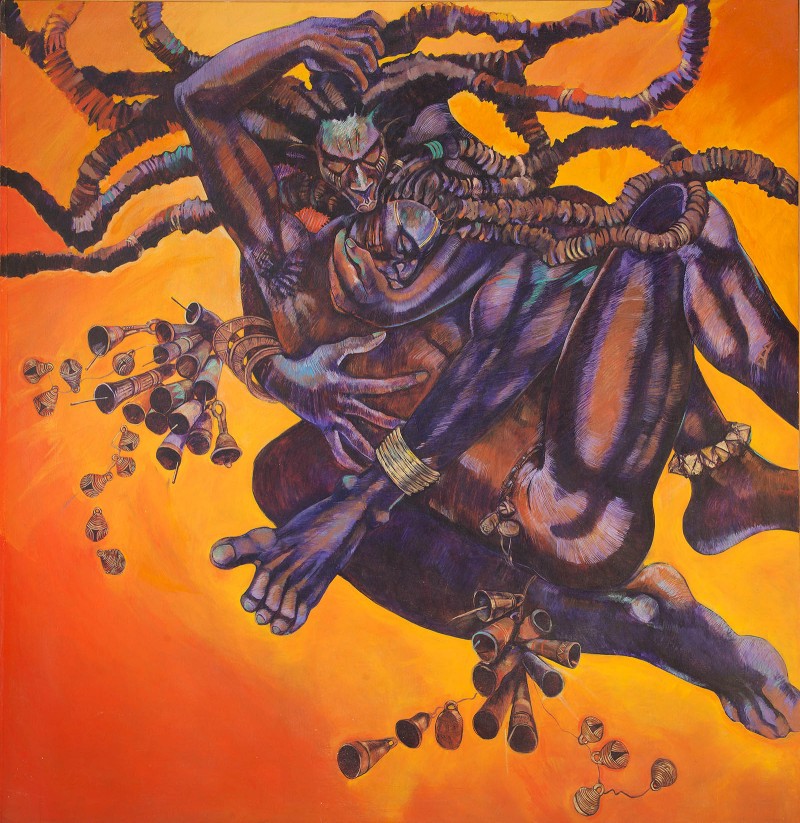

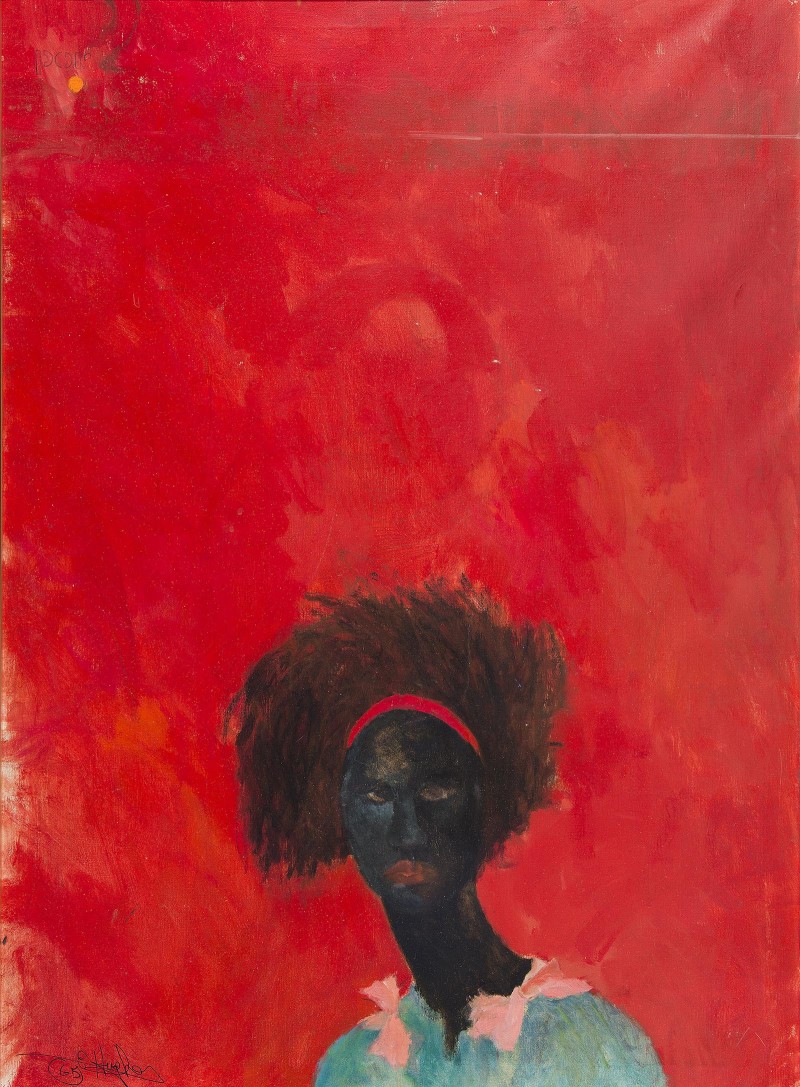

Roland Ayres’ “Cataclysm, Rebirth New World” (1968), a pen and ink drawing, is a modern version of Hieronymus Bosch’s depictions of a world in chaos. His extraordinary imagination and virtuosic technique reveal a first-class illustrator whose work I was happy to discover. “Meet Miss Subway” (1965) by Edward Hughes is another standout by an artist I didn’t know; the bust of a striking young woman occupies at the lower right of the canvas yet commands the expansive red background, suggesting her emotional tenor. While I know Barbara Bullock’s current, wall-hung, multimedia constructions, I was delighted to be introduced to the exuberant palette and vertiginous composition of her 1982 painting, “Dark Gods”. She has learned from the best, Baroque masters—such as Rubens, whose “Prometheus” is the subject of an exhibition that just closed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA). And familiarity with Donald Camps’ monumental, frontal portraits did not prepare me for the subtle, almost Pictorialist quality of his earlier landscape photographs.

The Woodmere has assembled a picture of a self-organized community that thrived without outside help; in doing so, the museum enables the rest of Philadelphia’s art community to see what they’ve been missing and to open their doors a bit wider.