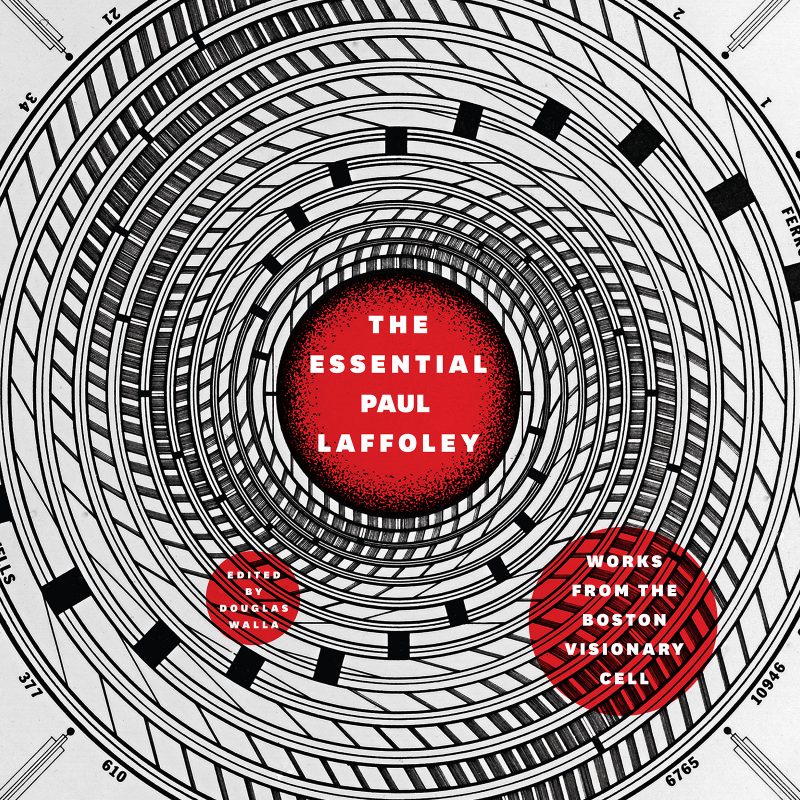

The Essential Paul Laffoley, edited by Douglas Walla

(University of Chicago Press: 2016) ISBN 978-0-226-31541-6

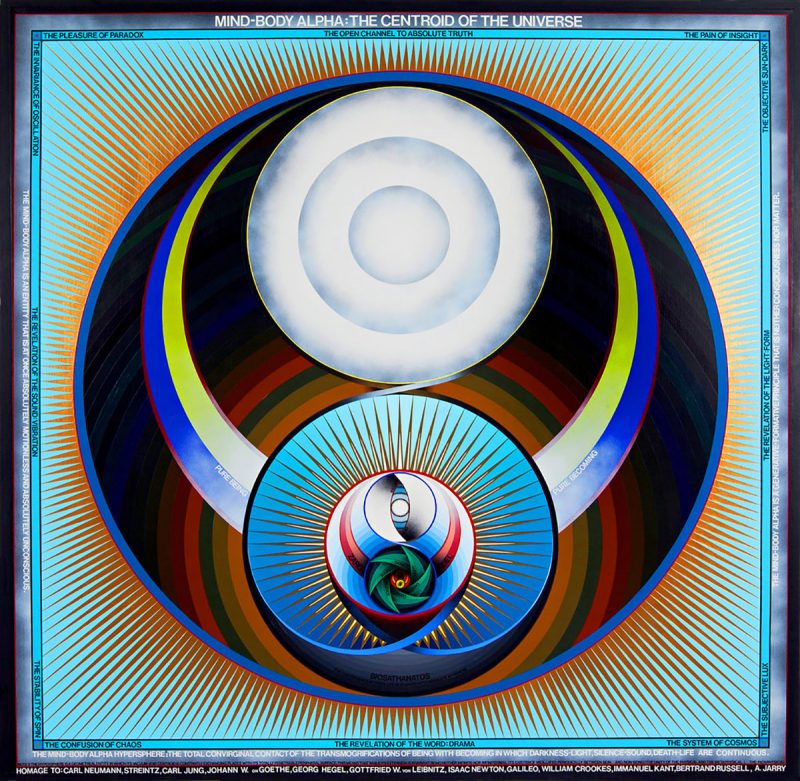

This stunning, indeed mind-boggling, monograph is the ultimate resource on the art of Paul Laffoley, whose works function as charts and diagrams of the Boston artist’s highly individual understanding of the physical, psychic, and spiritual world. They could be illustrations to a cosmology textbook written by a multi-authored committee which included Plato, Dante Alighieri, Giordano Bruno, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, P.D. Ouspensky, H.P. Lovecraft, and the physicist who named “black holes,” John Wheeler. Laffoley was trained as an architect and self-taught as an artist, but he was hardly an outsider by any definition–although he has been mistakenly categorized as such. During the 1960s, having been thrown out of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, he spent several years in the midst of NYC’s art community, working for both Andy Warhol and Frederick Kiesler, the Austrian architect and sculptor affiliated with the Surrealists. Laffoley’s understanding of alchemy, religion, philosophy, spiritualism, history, literature, mathematics and the physical sciences, time travel, and space beyond three dimensions was largely self-taught, and the artist was an inveterate student.

Laffoley filled his paintings–and the occasional three-dimensional work–with as much written and visual information as possible and clearly enjoyed creating imaginative ways to impart his highly researched and pondered ideas. While many of his paintings resemble mandalas in format, it is unclear if he had any expectation that they would be used as aids to spiritual practices, or whether they were primarily didactic. The art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson describes them as “blueprints for the expansion of consciousness.” I must admit that I have never seen one of Laffoley’s paintings, many of which are very large, but know them entirely from reproductions. The artist contributed 1-2 page discussions of the ideas behind the almost one hundred artworks in the volume, each beautifully illustrated in color–although he sadly did not live to see the remarkable book which resulted. Lafolley’s writing is extremely clear–even when his ideas are not, and he occasionally slips in some humor, particularly in naming concepts. The volume includes an essay by Dante scholar Arielle Saiber on Laffoley’s illustration of the entire Divine Comedy, Linda Dalrymple Henderson on his interest in dimensionality and his art as a system of knowledge, and personal accounts by Douglas Wheeler, the artist’s longtime dealer, and by a friend, Steve Moskowitz, a scientific illustrator.

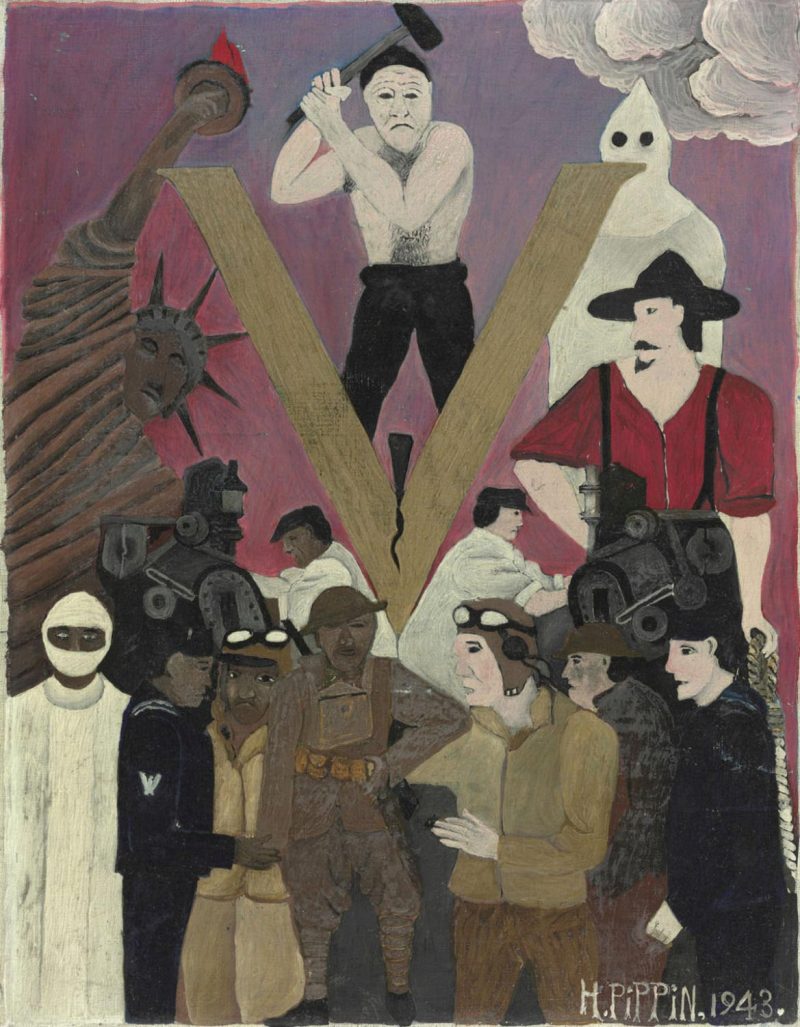

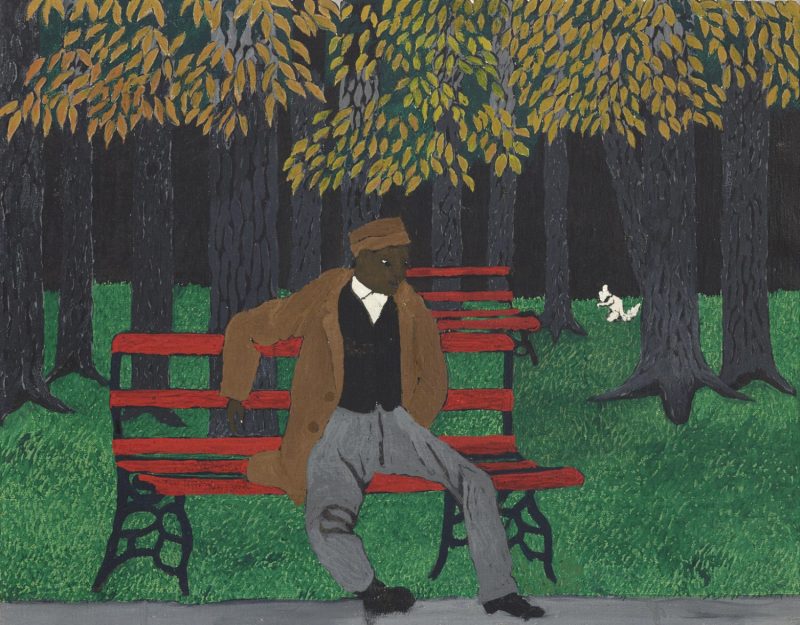

Horace Pippin: The way I see it

(Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, PA and Scala Arts Publishers, Inc., New York: 2015) ISBN 978-1-85759-941-1

This exhibition catalog is the first monograph on Horace Pippin published in more than twenty years and will be welcomed by admirers of the artist and by readers interested in art by African-Americans, the participation of self-trained artists within the mainstream art world, and the persistence of biblical and historical subject matter into the twentieth century. The volume is handsomely designed and printed, with excellent illustrations.

Pippin began to paint after WWI when an arm injury incapacitated him sufficiently that he received a disability pension the rest of his life. He was not isolated from the world of high art, however. He was represented by dealers in Philadelphia and New York who showed work by mainstream artists, and after 1940, when Albert Barnes acquired one of his paintings, Pippin visited the Barnes Foundation.

The monograph is exemplary in emphasizing a self-trained artist’s work rather than his biography. Anne Monahan discusses his multiple sources and treats him as a serious artist, rather than as a primitive who either created paintings which mirrored the reality before him or copied work by others. Jacqueline Francis looks at Pippins’ sources in popular culture and standardized depictions of African Americans in various household items such as salt shakers, lawn jockeys, and children’s toys. The article by Edward Puchner examines a single painting, “Mr. Prejudice,” within the context of race relations during the 1930s and 40s, the situation of African-American WWI veterans who returned to racist policies in employment and housing, and the persistence of a segregated military into the Second World War. There are three further essays, an index and bibliography.

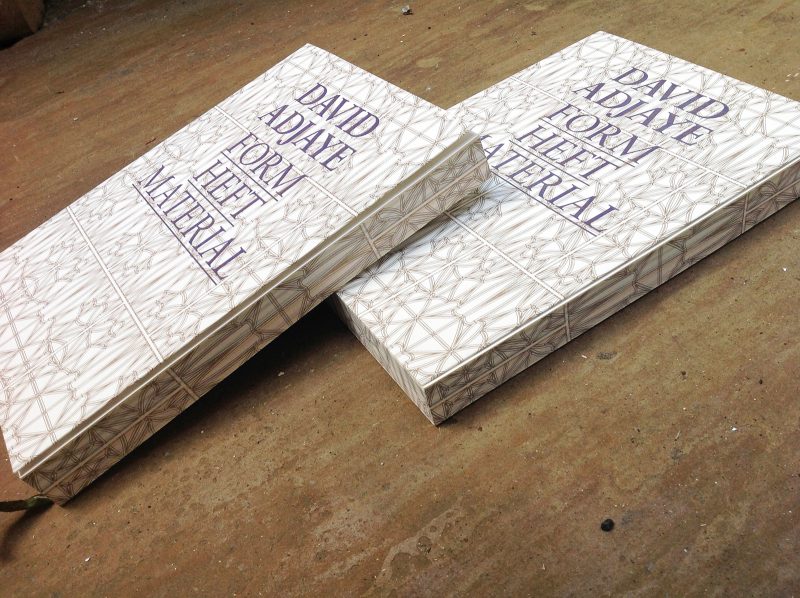

David Adjaye: Form, Heft, Material, edited by Okwui Enwezor and Zoe Ryan

(Art Institute of Chicago and Haus der Kunst, Munich with Yale University Press, New Haven: 2015) ISBN 978-0-300-20775-0

This beautiful, modestly sized book is the catalog to an exhibition on the Tanzanian-born, British-educated architect who has offices in London, New York, Berlin, and Accra. Smaller in format than the usual architectural tome, it does not attempt an in-depth visual investigation of Adjaye’s work, which has notably avoided a signature style. It is, however, an excellent introduction to the interests, approach, and building record of the architect of the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Since tickets to the museum have been fully booked for the coming year, this would be an excellent gift for anyone waiting to visit, as well as any reader interested in current architecture, urbanism, trans-local approaches to the built environment and the incorporation of non-Western building traditions into contemporary architecture.

Adjaye published a monograph on urban architecture in Africa following ten years of research across the continent, and he discusses his interests in the subject, which are clearly integral to his practice. While sensitive to the symbolic content of both indigenous and colonial buildings, he acknowledges the skill with which colonial architects addressed harsh and often unfamiliar climates. Five scholars analyze aspects of Adjaye’s work, including his methods and approaches, his ideas about the political possibilities of public, urban spaces, his place as a post-colonial architect as manifest in two museums and a community center, his conception of typologies of urban buildings, and his solution to the form the new Museum of African American History and Culture would take within the Smithsonian complex.

The book’s design–by Mode, London–befits an architect known for research into materials and their sensitive use; it is a beautiful object, from the incised typography of its cover and patterning that wraps around the sides of the pages, to its use of multiple papers which differ in color, weight, and texture. The book includes a list of the architect’s projects by type, including his research, exhibition designs and collaborations with artists. The writing is approachable to non-specialists.