Shona McAndrew’s life-size sculptures of big naked women are realistic enough to make passersby on 5th St. do a double take. In Moira, a show titled after the artist’s mother, paper mache sculptures and digital photo collages depict these women at home in their bodies. They are not posing for an audience but are engaged in actions at once banal, intimate, and humorous, like brushing their teeth while crouched on a toilet, or lounging with legs splayed open on the bed, surrounded by cats, Converse sneakers, and bottles of shampoo. McAndrew’s digital collages, some of which use photographs of her sculptures, others of which use photographs of their creator, situate these women in densely patterned interiors. In the background of her scenes, nudes by Manet, Modigliani, and Matisse point humorously to the male gaze that dominates the Western canon.

Leah — As an undergraduate at Brandeis University, you majored in both art and psychology. Did your studies in psychology influence your current practice as an artist?

Shona — Definitely. I think my work is therapeutic for me in trying to figure out different aspects of being a woman and being myself. It’s not therapy art, but it’s a means for me to think through myself and think through my interactions with other people.

L — Was there a piece you made that was a turning point in your practice?

S — My Master’s degree at Rhode Island School of Design was in painting, but I felt very stuck in painting because I set myself limitations I couldn’t overcome. With sculpture it’s different. At RISD, I made one really crazy oil painting with a view, and all these flowers, and a catalog of women sort of hanging out. And I just hated it. I spent so much time working on it and I just hated it. My first show in New York was in six weeks so I thought, why don’t I just make something really crazy. So I sculpted a memory I had of hanging out by the river with my best friend, and she had her arm up and I started poking her armpit hair. I thought it would be a very funny sculpture to make, and it felt very intimate and true to myself.

There’s currently a sculpture of mine at the Museum of Sex, and it’s of a woman named Norah twirling her pubic hair. I found a notebook from my first semester at RISD, two years before I made that sculpture, and in it I almost exactly describe the idea for that sculpture. I remember thinking, “I’m never going to make that sculpture, I’m not a sculptor,” and then two years later I make almost the exact same idea. I think the best ideas are those really crazy ones that you think there’s no way you can do.

L — Two sculptures in Moira show you with your partner. Are those works different for you from the others?

S — All the other women are straight from my imagination, they’re pure inventions. For the two of Stu and I, they’re as much about us as they’re not. I was more interested in capturing our experience than our exact faces. A great professor, Kevin Zucker at RISD, told me the big one would be when I finally got to sculpt myself. Every sculpture is not me, but obviously resembles me in many ways, and I work from knowledge of my own body. But it was different to finally make myself. I have body dysmorphia, and I’ve done a lot of transformation the past two years. When I was making the sculptures of me and my boyfriend, I was very nervous to see what my our bodies would look like together naked. From my belly button to my back is as wide as he is from hip to hip. I started off thinking I would be horrified at the result, but now when I look at it I just think we look so right together.

L — What’s the process of making these sculptures like?

S — They’re made out of paper mache, which I started using because I saw a video of a woman making a paper mache dog. She was using a balloon as the body, and it was very basic and very silly, and I thought, that’s the skill level I have! Paper mache is easy, but it’s actually very hard to get it to the level where my sculptures look. My boyfriend, Stuart Lantry, is an artist who works with metal, so the sculpture on her tippy toes is the last one I made with a wooden frame. Every other one has a steel frame, like a stick figure, and it’s just paper that I tie up with tape. I crumple it up, then add layers of paper mache. Then to get the details I use paper clay, which is paper made into clay form. It takes hundreds and hundreds of hours, including a lot of boring stuff like sanding for a week straight. I form a connection with them, because I’ve spent like thirty hours on that one arm, by the time they’re made I’ve almost forgotten I’ve made them.

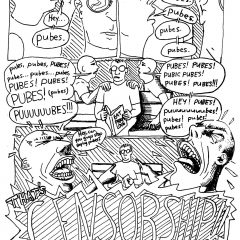

L — Tell me about Instagram’s censorship of your work.

S — It happens a lot. Some of my sculptures get reported within seconds. I was looking at the Instagram account for Sports Illustrated, and there’s a lot of imagery and videos on it that cross a line miles before I ever will. But those pictures stay up because most people who go to their account aren’t shocked by their images and actually want more of them. Whereas if someone who stumbles on my account doesn’t appreciate body positivity or sculpture, they’ll just see naked people or pubic hair or fat boobs and they’ll report it.

There’s a thing called shadow banning where Instagram keeps your profile insular, only promoting it to people who already follow you. And when you use Instagram as your business—because a lot of opportunities for artists happen through Instagram—it’s hard to reach out to new people. Last week I wrote something for Artists Against Social Media Censorship a website run by Joanne Leah, that features stories from artists who’ve been censored. Of course most are women. I feel both horrified and excited that my work is being censored. It’s a weird feeling because I know that’s why I make work, which is that people may not want to see these bodies.

L — You’ve mentioned you like seeing people interact with your sculptures. Who do you think of as your primary audience?

S — The sculpture “Norah” is at the Museum of Sex, and I like seeing the hashtags because she gets photographed a lot — boys looking at her crotch, guys on their knees praying beside her. My work is very easily read by art lovers. There’s a lot of art history and references to the male gaze and female gaze, but it’s also accessible to other people. I don’t want to say I’m a woman artists making art for women. I’m trying to speak to any viewer, but I want a woman to look at my sculpture and think, “I do that, and she looks kind of beautiful, so maybe I can be beautiful too.”

Moira, McAndrew’s current show of sculptures and digital collages at Pilot Projects, is on view (by appointment) through Friday April 20th.