The cyclical redistribution of whiteness in arts institutions has left me malnourished. Once or twice a year I attend a major exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art and feed. These shows that center blackness (Speech/Acts, The Freedom Principle, Rodney McMillian: The Black Show) have been transformative for me and a reminder of how frustratingly rare it is for marginalized people to see themselves, their culture, their history, in art museums.

The Last Place They Thought Of, current Whitney-Lauder Curatorial Fellow Daniella Rose King’s culminating exhibition continues the museum’s practice of centering black voices. On view through August 12th, the show features work by four black women artists: Jade Montserrat, Torkwase Dyson, Keisha Scarville, and Lorraine O’Grady. King gathers these artists’ explorations of place and identity to consider how black women’s experiences might figure in building a new understanding of geographic space. The Last Place They Thought Of ventures to relate the realities of black femininity through representation and abstraction, fantasy and documentation.

An Expansive Presence

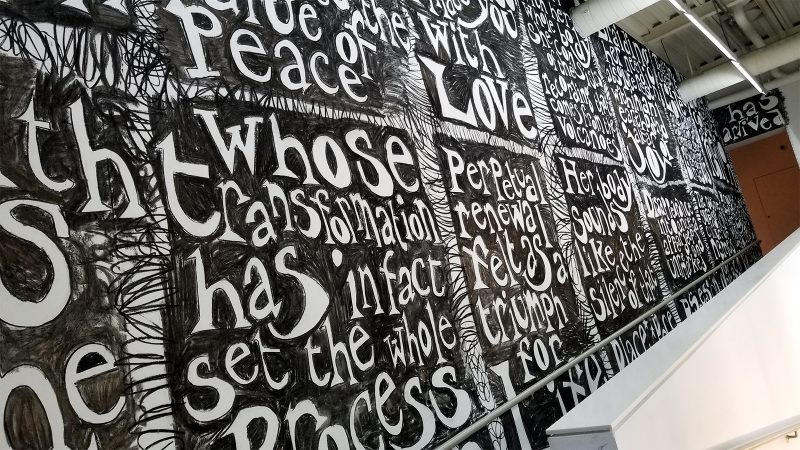

“Untitled (The Wretched of the Earth after Frantz Fanon),” an expansive text drawing, fills the walls on the ramp connecting the first and second floors of the museum. British artist Jade Montserrat has applied charcoal directly onto the walls, presenting each sentence of her text in a box rather than on a line and occasionally allowing words to proceed vertically rather than horizontally. The first sentence as you climb up the ramp reads, “My dear friend I know that you, and you alone, possess peace.” That first line is indicative of the auspicious, clairvoyant voice of the piece. Combining writings from Josephine Baker, Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, and Donna J. Haraway, Montserrat collages a poem that is both omniscient and earthy. The text goes on to describe a woman placing her body, her gardening, her braiding in relation to peace, freedom, and love. The expansive femininity that Montserrat produces feels as commanding as the presence of the installation itself.

Under Cloak of Darkness

Keisha Scarville’s “The Placelessness of Echoes (and kinship of shadows),” beckons the viewer into the corner of the gallery space. This series of photographs was taken at night by the light of the moon and stars. In the shadows Scarville reveals the outline of trees, the contours of a woman’s body, fabric mysteriously residing in the forest. She uses the darkness not as an indication of danger, but to depict a place where trust flourishes. Through “The Placelessness of Echoes” Scarville ruminates on the inability to tell one’s own body and nature apart when darkness shrouds the vision. Her work reminds me of stories about runaway slaves—the tenderness of one particular photo of a woman’s hair, coarse like mine, briefly brought my own body into the “Placelessness.”

Diagraming History

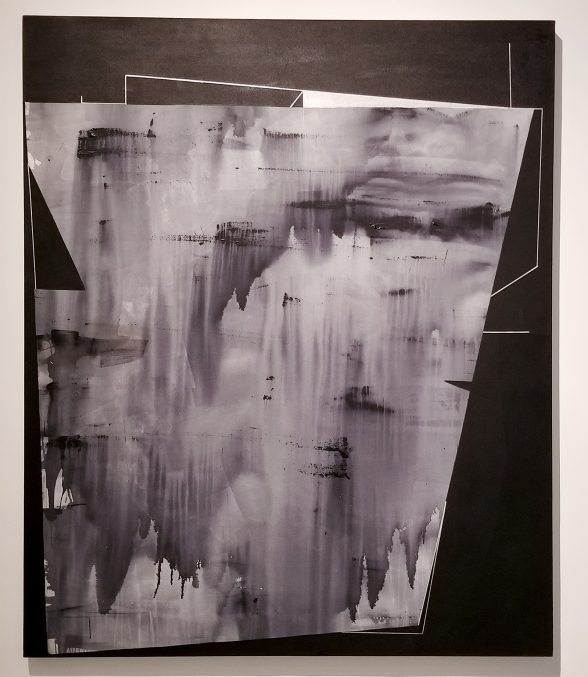

Torkwase Dyson’s four paintings, from her series “Water Table,” use the material explorations of Abstraction to meditate on the histories of water and geography and their relationship to slavery, colonization and industrialization. Each of Dyson’s paintings consists of a singular boxy form on a black background. The rectangular objects are filled in with washes of light gray paint and contrast starkly against the black. Thin, silver lines of paint mimic graphite marks as they outline and extend beyond the forms. The paintings function as diagram, blueprint, and memorial. Dyson crafts precise and evocative images, though her research and practice — which includes deep sea diving at historical coastal points— are vastly richer in writing than on canvas.

Scalp Politics

The ambient sounds of Lorrain O’Grady’s video piece, “Landscape (Western Hemisphere)” drift throughout the exhibition. Her single channel video rests in its own cove at the end of the gallery; here the viewer confronts the sounds of dusk and of lapping water. O’Grady’s video features her own hair, a close-up look at her coils as they sway and shake. A visual comparison between her hair and tall grass blowing in the wind is immediately apparent. The mesmerizing, 18-minute video is not merely a comparison of body material to nature material. That O’Grady allows us to peer closely at her scalp is extraordinary. The policing, mutation, and rejection of black women’s hair has dislocated this part of our bodies from ourselves. Intimacy with one’s own natural hair is an act of reclamation and the sharing of this intimacy is a declaration. O’Grady gracefully declares her presence and washes the viewer in it.

As excited as I was to see The Last Place They Thought Of, and as rich as I found the work, I left the show feeling bloated rather than full. The connective thread between the four artists was lost on me, and because the curatorial statement provided so many concepts, constructs, and theories to consider, it was difficult for me to parse out the show’s intentions. As I considered the intensity of my disappointment, I started to wonder: is it possible that I am asking too much from shows by black artists? Could it even be that the wide range of themes in the curatorial materials asked too much of the artists in the show?

When there is a scarcity of black art there is a pressure for it to be ingenious and powerful in order to be worthwhile (twice as hard, half as much). But, blackness does not have to be spectacular in order to exist. While I felt let down by my experience with The Last Place They Thought Of, I by no means think the show is weak. I wholly look forward to following Daniella Rose King’s career as she continues to make space for marginalized voices and recommend this show be seen by all.

“The Last Place They Thought Of” is on view at the ICA through August 12th, 2018