Our September 23rd LIVE zoom event, “Art and Social Responsibility Today” with Ken Lum and Karyn Olivier, was a huge success! We were honored to welcome Karyn and welcome back Ken to revisit our original Art and Social Responsibility project, 5 years later. Thank you to all who purchased a ticket in support of Artblog’s 17th Birthday & Auction celebrations. Because of your participation, we exceeded our fundraising goal.

Artblog’s mission is inclusion, so we wanted to make sure this conversation was accessible to all. That means we uploaded “Art and Social Responsibility Today” to Artblog Radio and Artblog’s Youtube, and transcribed the talk! Whether you’re a first time listener or a re-visitor, you’ve come to the right place for a meaningful discussion about public art, gentrification, arts funding, and more. Scroll down to listen, watch, or read today.

HUGE thank you to our moderators, Olivia F. Menta and Jacque Liu, and Sponsor, The Sachs Program for Arts Innovation.

You can listen to Artblog Radio on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Thank you to Kyle McKay for composing Artblog Radio’s original podcast intro and outro!

Artblog Radio

Youtube

Transcription

Matt Kalasky: This is a Zoom room and technical issues do come up. So if any of our moderators or panelists timeout, or there’s glitching out, just be patient, we’ll get back to the goods as soon as we possibly can. All right. Olivia.

Olivia F. Menta: Thanks, Matt. So we’re now on day two of three of our annual auction and fundraiser.

Thank you to all of the artists here tonight who’ve donated their work. I want to thank our auction sponsors, Jeremy Frank and Associates. Voyage Actually, Practical Reasoning Analytics, Seven Arts Framing, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, Fishtown Animal Hospital, Mark J. Monroe – Griffith insurance, LLP, and La Colombe Coffee roasters.

Now to tonight’s program. I want to start by making a huge thank you to the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania for sponsoring tonight’s talk. I especially want to thank the Sachs staff, John McInerney and Chloe Reison for their continued support. So to introduce our speakers….

Ken Lum is an artist, writer, Pew fellow and Marilyn Jordan Taylor presidential professor and Chair of Fine Arts at the Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. Lum’s political and identity focused work has received international critical acclaim. Ken participated in the original Artblog, Art and Social Responsibility conversation back in 2015.

Karyn Olivier is an artist, Pew Fellow and Associate Professor of Sculpture at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University. Her historically informed interdisciplinary works have won numerous prestigious awards and have been exhibited internationally. And my co-moderator Jacque Liu, former Percent for Art project manager, Philadelphia Office of the Arts, Culture, and the Creative Economy.

And myself, Olivia Menta another co-moderator, I’m an Artblog board member along with Jacque , and, uh, I’m the Executive Assistant and Project Manager at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture. So we’retgoing to spend the first 30 minutes on questions and then we’d like it to open it up to our audience to allow for a dialogue across us. And while we’re talking, if you think of a question just as Matt said, pop it into the chat. So that was a lot, now for our first question.

Ken. Karyn, are there any, are there any specific stories or people who have shaped how you make art specifically as it relates to social responsibility?

Ken Lum: Okay.

Yeah. There’s many people. Um, you know, well, first of all, I think it’s better to answer it this way. When I merged entered into the art system, it was during the tail end of conceptual art. There was, at least discursively the sense of opening that was unprecedented, that involved the inclusion of otherness, uh, women, artists of artists, of, uh, sexual difference that could announce themselves publicly as so, and artists of color, and also, um, inclusion of artists who lived along the margins as opposed to the center of the art system. And so I was shaped during this moment when, uh, a lot of conceptual art is at least in terms of their, in terms of the, the articulation of the work dealt with this idea of a globalized world, a globalized world that was.

Well, it’s unified and also breaking up at the same time, uh, into, you know, normal points and, and build villages and little communities and so on. So those artists would be like Dan Graham, uh, Martha Rosler, uh, James Collins, uh, artists like that are ours that were Fluxus artists, you know, um, Adrian Piper.

So a lot of the – Clark- a lot of those artists were, were still actively, uh, uh, making work at that time. And, uh, I feel very lucky, uh, that I was shaped by them at that time.

Karyn Olivier: I think for me, it’s maybe a little more personal, um, I don’t know how interesting it is. I think about how I started art late.

I decided to go back to school at 30 and study ceramics. And I remember when I started making work, I think I was. Acutely aware that I didn’t have the skills, I didn’t have the background. And I kind of was very interested in just thinking about what was there. I remember, um, also thinking about, I wanted my family to be interested in, I mean, from my immigrant family, I wasn’t supposed to be an artist that wasn’t the plan we have doctors, lawyers. It’s that kind of story. My parents worked two jobs while going to school for a purpose, not for me to be an artist. So when I started making work, I definitely wanted my family to get it and to be engaged, I wanted my niece and nephews to get it. So I engaged like playgrounds and things like that. I think also about, um, being from Trinidad and carnival is a big part of the culture.

And a lot of it is about making do or what does it mean that what’s familiar, um, gets, becomes strange. It’s about the simple means of making. You take a cloth, you put it on your face. It’s a mask. You take piece of cloth, take wire, you make bat wings and you’re a bat. So something about like the, what if something about the possibilities, something about a future being lived now.

But I also think about those 10 years, you know, between college and, and grad, when I went back and studied art. I used to work at Bloomingdale’s is a as a buyer for designer handbags and store manager of different, different, like retail management stuff. But I remember I used to pass by my way to the DeKalb Avenue, train station, this billboard, and I would see it every day and it was, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the one of the unmade, the unmade bed.

I remember every day wondering what that was. I was like, I don’t think it’s an ad. And I was thinking about ads, of course, cause I’ve working in a retail fashion kind of industry. And I kept thinking about the narratives and possibilities. And of course it was how many years later that I discovered, Oh, this is a very important, artist. I like that idea simplicity at the every day.

I like that, that work made me the repeat viewings kind of allowed for possibilities and their opening up of what it could mean for my own life. I liked that. It was both. Personal, but what it means to display the personal in that public realm. And then of course I found out the politics and, and I think, I think about that in my work.

How do you have something that kind of has someone recognized, but then there’s that maybe there’s something that I assume and that assumption maybe gets challenged, but then allowing a space for you to enter the work as well. Yeah.

Jacque Liu: It’s really great to hear about all of these sort of like shared experiences, you know, that you, you both seem to have, um, moving to thinking about how that relates to sort of social responsibility, you know, like both of you, I think, um, deal with in a very personal way in your work, um, social responsibility.

Um, I love to hear perspectives on how you think public art engages with the community, both in the present date and historically.

So sort of to guide that my question is what role does public opinion play in the artistic process? What role do you think it should play?

Ken Lum: Well, first of all, I think, um, you know, uh, social purpose for art is different from, uh, you know, if you asked me, uh, should, should, should, um, an individual, me as an individual should live life as an ethical person. And I feel like I have social responsibility as a, as a, that was a good citizen to better the society.

That’s slightly different from asking me as an artist. That same question. I’m more interested in, in what, what is the role that are placed and how does art play its role at its best capacity? And, and often, you know, we know that for example, form and content, um, functions in a very diametrically opposite to, uh, uh, relationship to the way we expect it to work.

That is this content which we tried to deliver often appears paradoxical to the form. It takes. Right. And that’s the magic of art. It doesn’t, it doesn’t necessarily have to be predictable or consistent in parallel also. Um, and so as an artist, I think, you know, that’s how it was that to that question of, um, uh, of arts kind of social functioning.

Now, art in a public context? I think for any artist that wants to make public art, you have to, first of all, imagine, and you know, in kind of predetermined science, what is the audience? Who is the audience? What are the audience? What are the multiple publics that make up that audience for your work? Even before the work is in place.

Right. And, uh, and I would say that, um, it doesn’t require the engagement of that. So many processes do. Right. But ultimately, you know, as an artist, I will try to read that, uh, response from the public and, and take it into account. But ultimately I will be making the decision in terms of the, in terms of the composition, the look, of the work.

Karyn Olivier: I don’t really see a difference between the role of the artists and a person. I mean, I tell my students, my most important job is just to remind each other that we have to be active and engaged citizens in the world. I think about, I don’t think about my responsibilities equal to the viewers it’s equal to the public.

If anything, I think about our accountability in terms of being. Empathetic with each other, our accountability and making sure everyone to the mo- to our, most of our ability or to help people to have agency. Um, I think when I think about social responsibility, it’s such a there’s it’s, there’s no ab- to me there can’t be an absolute because every, every situation is different. It should be kind of treated as such, um, be it the demographics, be it, the history, the historical nature of the site. I mean, I just feel like there’s so many things to consider that there isn’t kind of one way, but to me, key is I think about like the empahty, agency and I always go back to Bell Hooks that love is the most radical act and a political act.

So how does that engage on these public spaces, but it’s specificity specificity. So the idea of like your original question was something about this public opinion. I think that’s too soft in a way it’s like, I think of it as an active thing. Like let’s get in this and, and because we’re actively engaged because we’re gonna have some sort of democratic thing happening. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily consensus.

Ken Lum: If I could just add to that. I think I agree with Karyn in terms of public opinion, being too soft in the sense that it depends, you know, if you’re just to canvas people in general, I’m not sure how much value I would place it in terms of that opinion, right?

Because you would get maybe platitudes in response, but one, one, um, um, set of opinions. I do value are, are, are, the, the opinions of the underclass. Of the people who are really oppressed. Of the people who are really at the limits of what’s what’s what constitutes the citizenry, uh, of the United States.

Those people are never heard those people, their opinion. I always try to take into account, uh, because I think their public voice is not only not heard, but the most. Uh, wise and most meaningful. And so, um, when people say, well, should you, should you poll the immediate, uh, environment of the site, the public that lives there, is their opinion of value? Yes, it’s of value.

But I would say it’s also limited, in terms of that. And so, because there’s a lot of people that may be, you know, they like going to a Philadelphia Eagles games on Sunday, but maybe they’re not that interested in art. Right. So, and it doesn’t bother me. Right. So, so it’s not that I don’t value them as fellow citizens.

I just don’t, I’m not going to over determine the value of their, their opinions. So, so that’s how I would answer it in terms of the question of public input.

Jacque Liu: So what I’m hearing then is,

Karyn Olivier: Wait, were you speaking in reference to like a public art commission where… the community has a say in either voting and things like that? Because I think that also depends.

I did a project at University of Kentucky and there were people who gave their opinions, but they were students or faculty there. Not that their opinion didn’t matter, but I just didn’t have that weight. We were kind of like on the same place, but then when I’m doing a project. The Dinah Memorial, where I’m actually dealing with the community that actually has been overlooked, that is oppressed. You know, when someone, when we had several community meetings and one of the final community meetings, when I kind of presented my revisions and revisions, you know, a community member, um,said why don’t you add this to the project?

And one I took it, because it was someone highly respected. Number two, it was super smart and it was, number three, it was something that I should not have overlooked. Like the thing she posed with something that. Yes. I live adjacent to that neighborhood, but I’m in Germantown. I’m not in Nice Town. So she was able to see something that I just couldn’t see. So I was open to listen and there were other things people mentioned that I’m like, actually, no, but there was like, what, who is the person? What is their position? How invested are they? I mean, I was someone who went to every single meeting. It was like lives there. It was like committed. So I think that like, again, it’s like, It does. It’s a circumstance and we have to be as artists sensitive.

Again, it goes back to earlier, what Ken was saying, it can’t be, we’re not making something that everyone’s gonna just like, or it’s visually appealing or taste is irrelevant on some of that. You want to seduce people to kind of engage for a moment, but it’s not about pleasure necessarily. It’s not about it’s about the questions about the inquiry. Being a site of inquiry, right?

Ken Lum: I totally agree with that because often I’ll do a public art piece and rather than just, um, see to some, you know, nondescript poll of all kinds of opinion from that area, I’ll get to know people and i’ll find certain people, I find much more interesting than other people, right.

And then I will ask and seek their opinion. And I think that’s more particularized.

Jacque Liu: So for me, you know, like as someone who’s worked in the public art sector for seven years, that question is exactly how you approached it. I think that you both know, and I think really it has to do with, um, uh, you know, you both, I think are clearly, very good at empathetic and active listening.

And you don’t necessarily have to know exactly. Uh, you know, you’re not checking boxes in order to engage what the community sentiment is. And I think at the heart of that question is how can we as artists, you as artists help others who are in the position of doing that –city planners, et cetera– help them do that because they don’t have these super powers that you have.

So what is it about that, you know, like, uh, how do you, how do you come about those powers? Is it something in your training? Is it something personal? You know? Uh, it can be anecdotal.

Ken Lum: Okay. Um, that sounds like a Karyn Olivier first response question…

Karyn Olivier: Hmm…

Ken Lum: I mean in many ways, you know, city planners and, you know, they they’re, they function in a certain way. They think they have a worldview because of their training and, and it goes up, you know, it’s like this distinction between a lived experience, and conceived experience, anyone’s read Henri Lefebvre, “La production de l’espace” right? And so on.

So. Um, you know, the difference between what he called social practice and the difference between social practice as lived, that’s two different things. So, you know, there’s a kind of tension there between a refining. And so in these kinds of public art, um, processes, You know, fortunately, or unfortunately, you know, it goes through planning, it goes through and, uh, all these administrative departments and you have to be savvy enough to understand their language, understand their culture and also persuade them.

But I find, um, um, that if, uh, you know, most planners are very open to two artists, there’s sympathetic to us, but it is, it is, um, it is a challenge to, you know, Persuade and to argue for, for your ideas.

Karyn Olivier: I think too, it’s important for, I tell my again, I feel like I’m equal parts, artist and educator. I tell them the importance of having different publics for your work and within that there’s different responsibilities to that.

Um, yeah. Give me your question again in a different way? Like, I guess… hm. Give your question in a different way.

Or just restate it.

Jacque Liu: Well, look, Olivia, you want to ask a question? I have another one that I think was relevant. That was the longest thread, but I want to

Olivia F. Menta: Well, I wanted to talk a little bit about, I want you to get the conversation a little about, about permanence. So there’s a longterm permanence yet temporality with public art it gets weathered, abused, loved, tarnished.

And my question really surrounds should we be, should we be preserving art? Can it be done responsibly? And how do we preserve art that conflicts with our contemporary ethics and social standards?

Ken Lum: Well, you, you cited yourself, Olivia, you know, the, the so-called permanent of art or seeming permanence of art is, is maintained, right? It’s it’s and it’s expensive, right. Even bronze, which has been around for thousands of years. Needs to be maintained. It needs to be waxed needs to be cleaned. Uh, you know, probably twice a year, if you’re near the near the sea, it probably should be four times a year.

And, uh, and you have to have a budget for that. Right. So it’s not, otherwise it will oxidize it. Yeah. Start breaking down over time, like anything, right. The force of the entropy would take over on. So. But I think what you’re speaking about is, uh, monuments and, and their, um, projection of permanence of that they, they represent a kind of, um, content that, that is supposed to endure, uh, uh, in that, uh, you know, through infinity and so on.

And, uh, but I think that’s a convention that’s, um, That hasn’t really been born out in history because monuments come down all the time throughout history. Right. And so on. So, um, because history gets budget’ng revised, constantly being reconsidered.

I actually think that’s healthy. You know, and so on. And I think, but I think another path which would be even healthier is if. Um, counter poised histories. Many, many other histories because there’s many histories that take place at the same time as the dominant history is unfolding. If they were allowed to also be recognized in the dress, then that would mitigate, um, you know, this question of the, the, you know, the unitary permanence of, of, of, uh, of the dominant narrative monuments.

Karyn Olivier: Yeah. I think we just have to kind of. Open up to just because of materials can be permanent. Doesn’t mean it has to last, it needs to be displayed forever. I think about my piece that I’m working on for Dinah. I like that it’s going to age and they won’t be about cleaning it up, but like, I want to see the aging of the stone.

I want to see the Moss. I think it depends on what, when it’s, how, how the work is supposed to serve. Sometimes I think about monuments. I think about the living, breathing entities. So in that, when is it okay for them to kind of show that history, but then you have something like last summer, the Frederick Douglas statute being ripped out.

No, that needs to go back. The location of, of him living there, the location of that speech. Of course it has to be repaired. So, but how do we decide collectively, like, you know, monuments are there for society to be collective, decide to agree on something, but who’s deciding, I’m going to say of course of Frederick Douglass should be there.

Hopefully we all kind of socially and kind of could believe a certain things matter. So, but I think, I think that’s a tricky thing I was thinking earlier about when you were asking the early question, we can go back to yours when I was thinking about the public artists and what they, what they can do. I think artists get too caught up in worrying about… we’re so in the capitalist structure that they think that we have to like, public art has to be about beautification. And when they’ll be city planners, when they want to beautify, it’s like, no, no, no beautification isn’t , I think when we said let’s do it, let’s do it because I want to have a gig. I want to get paid.

I want like ha. But if you realize, I remember Hank Willis Thomas told me once, because I feel that, well I told him that some of the work is a little too simplistic. I think he’s a great artist. Um, he’s like, yes, but that work it’s constantly being sold and allows me to do these other projects. So, what does it mean to have your works functioning in different ways?

And not that you don’t believe in all the work, but wasn’t me for me to make sure potentially I could sell something here, but then I don’t have to kind of give in, in this other space, I don’t have to kind of succumb to that public. I’ve had public art pieces where I’ve kind of decided not to do because I realized it was a beautification project.

I mean, I’m only, now this year- 52- going to have a gallery in New York. You know what I mean? You could still have that happen. So like, how can you be conscious of what, how we’re being played, how we’re being used. You have the agency, this whole, everything, everyone else goes away without us. So how do you demand it?

Yes. There’s always someone else who’s willing, but I go back to Confederate monuments. Artists made those monuments. How did we agree to that? You know what I mean? So, okay. I’m going to stop my rant for a minute. Yeah.

Jacque Liu: Well, okay. So sticking with monuments, let’s get real specific here. The real nitty gritty, right? Philadelphia. We have a couple of monuments, which are one has come down. Rizzo statute came down last, last, this year, this summer, it seems like last year. Cause. Time is irrelevant. Now, um, Christopher Columbus is scheduled to come down.

I’d love to hear you both talk about the role you think that these statutes play in our history as Americans and the role they will assume after these present day conversation.

You know, and I, I know where I fall. I suspect most people on this call fall on that same side of things, but I’ve also met a lot of people who said that this is part of our history, regardless that it’s been taught. So we can’t ignore it. And so I, I think I want to sort of, as you’re saying, as both of you have been saying the different audiences, you know, like, so. What do you think from that perspective?

Ken Lum: Well, first of all, Karyn Oliver mentioned she’s 52, but she looks like she’s like 28.

[laughter] So first of all, it’s not as you know, because the Rizzo statue came down right. That somehow, he disappears from history. He’s in the history books. You can look him up and he’s probably got a Wikipedia page. Right? And, uh, you could, you know, the history of Philadelphia will has covered and in the future, will cover some more his tenure for better, for worse.

So like he disappears from history. So I never understood that argument that somehow, you know, Oh, we have to preserve history because, you know, we take this down, which is talking about a piece of bronze. Right. Not a very distinguished sculpture. Why is that the embodiment of history, as opposed to all kinds of books that write about that, speak about Rizzo and his, and his tenure as police chief and later as mayor it’s already there.

So the history does doesn’t disappear. I’ll let Karyn speak. And then I have,

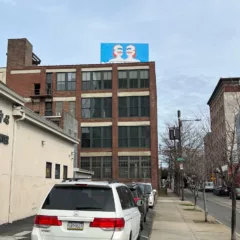

Karyn Olivier: Yeah, I mean, it’s, it’s it’s to me, I can’t not equate those with the Confederate monuments near their position there to be sites uh, to keep people and keep you in your place. ,They’re there as positions of power to show what matters to the cities. White, white, white supremacy matters. I mean, they’re in that same category. I mean, Christopher Columbus, my God, look, it’s just go in a little tiny bit into the history of that, of that man. And you like, how could this be? I mean, so certain ones, I mean our vote that Washington op-ed this summer and it, and I was kind of posing that there are certainmonuments, I believe have to go because of what they represent. We all know at this point, the Confederate monuments weren’t made at that time. They were made in specific moments, reconstructed, and made in civil rights. We know when those were made. They weren’t about that history so that, we could just forget about.

So what did we do? I’m interested in like, what are, are there any that, what are the things that are complicated that could potentially be used, and stay? But I think that there’s certain ones that kind of have to go, same to Christopher Columbus, how do we kind of debunk and get out of the history books where kids are still being taught?

We don’t even need his monuments because you look at the history and go, kids are being taught. They’re still being taught. That that is, that is the foundation of this country. So I, I, I have no worries about it never; melt ’em down. Melt ’em down.

Ken Lum: But I understand Jacque’s question. Um, because, um, I think you’re, you’re referring to the Italian community, Italian-American community who, um, themselves faced, um, you know, not a, a small degree of, uh, bigotry against them because they were considered swarthy southerners, you know, at the margins of the, uh, of, uh, you know, white Europeans and so on and so not quite white and right? So they suffered, um, their own kind of, um, You know, secondary status at one time. Right?

Karyn Olivier: Yeah, but but my thing is that, that should not be the statute to represent that.

Ken Lum: No, no, no, no. I agree. I’m just trying to make the point that, that, um, and, but that that’s also some time ago now.

That’s not like, that was a few generations ago. I don’t believe that, you know, a 30 year old or a 40 year old Italian today is going to go and have the same kind of feeling that Christopher Columbus represented this kind of unifying proud moment for Italian-Americans, maybe a hundred years ago, if you were Italian America, I’m not, I’m not mitigating, uh, you know, the kind of, um, negative aspects of Christopher Columbus.

Right? But I’m saying that one time that’s who that’s, who would be the embodiment. Um, of a kind of integrative symbol for Italian-Americans, but that was a long time ago. Right? And I think it’s, and I do think, you know, Karyn brought up education. You dig a little bit into Christopher Columbus, by the second trip, he enslaved 400 Native Americans. Right?

And that’s another history that’s not so, uh, talked about. The slavery that was visited upon Native American bodies for several hundred years. Um, and then not uh repealed around 1826 or 1827. Right? And then, uh, Christopher Columbus himself- why did he, why was he on this trip for? For avarice and greed and who was he sponsored by? He was sponsored by Isabella and, um, and Ferdinand. Right. And who were Ferdinand and Isabella? They were the Royal family that said let’s, “Hey, let’s prosecute this, the Spanish inquisition.” Right? So I mean, it just, and it goes on from there, right? So I think those facts also need to be known that narrative needs to be known and, and I, and up,

So it’s a failure of the education system. It’s a failure of, uh, and, and lack of courage, I would say. To take on certain topics because there was because certain people will say, well, we’re afraid of, uh, you know, the Italian or sponsor and so on. But I actually think that’s actually not, probably not true for most.

Jacque Liu: So might there be a way that these sculptures can educate then? You know, like subverting it from celebration to education?

Ken Lum: You mean by keeping them?

Jacque Liu: I’m just saying that… Yeah, actually.

Olivia F. Menta: Or erecting other monuments. Like there’s so many Italian Americans in history or Italians in history that represent very interesting social movements like Autonomia and Sacco and Vanzetti. I mean, there are Italians in history that I think many in the Italian-American community don’t know about…

Ken Lum: Yeah, they’re not represented

Olivia F. Menta: …to go back to Karyn’s point. And we don’t learn about them.

Karyn Olivier: Wholly. There’s certain myths we hold onto. And I think about history is told in fragments and it’s as if that we just picked-and-choosed the couple that kind of… appease white supremacy and said, “Let’s stick with those.” It’s like, well, we know that history is constantly being unearthed. So this fragmentary nature has to be looked back at., And now we start to piece together and realize, “We don’t need to hold onto Columbus! He’s like the bottom of the pile now!”

When we start, if we start allowing for the space to happen. Because the history is being uneartned, it’s just, who has decided to look at the archives, who’s decided to really do the digging. We’re a culture that’s very much likes to touch the surface. And artists are the worst. I’m the worst. Just enough acknowledge to make my work. And that’s a problem too when I was making my Atlas pieces, I said Karyn, you have to go in deep… because I’m so used to kind of like, “just enough.”

It’s like, I was like, no, sometimes we have to go in. And I think about that with educational system. That’s why people holding on to that.

Ken Lum: Well, I, I, well, Christopher Columbus is kind of unique in a sense that it’s not just about Christopher Columbus, but it’s also about the foundational narrative of the United States and he’s tied to that foundational narrative.

But the fact is, is that foundation on there, there was, was, was slave endemic. It was, it was all on the backs of exploited bodies, killed bodies, violence, and so on. Right? And people hold onto this kind of myth for fear that, fear that if we don’t hold onto this myth, then there’s nothing. Right? But instead of seeing it as an opportunity to kind of reinvent, right?

I mean, I think as an individual, I mean, I came to Philadelphia like eight years ago. Why? I saw it as an opportunity to reinvent myself. Right? Not, not, not, as a faker. I just mean reinvent myself in youth. In terms of a new, you know, and that’s always important reinvention. Right? And I think history offers an opportunity for a nation to reinvent itself, redefine itself, to become a better nation.

Olivia F. Menta: I think that also, I want to circle back on that permanence question. The idea of reinvention is so challenging for so many of us. I think. We know in COVID-19 how much change can really rattle us, not just in our professions, but as a community.

And so how, with making so many things of permanence, can we think about them flexibly, more adaptively, so that they can actually change in the future?

Ken Lum: Well, I think one of the problems with the monumental landscape, um, as it is, is that there are very few countervailing statues that deal with all kinds of worthy subjects. So what we have is, uh, re uh, iteration, reiteration of basically the dominant narratives. Right. This businessman was important or this guy was important, almost guys, right, in Philadelphia, you know, Sharon Hayes did the piece for monument lab, it’s only two women, uh full figure women, is, that’s historically presented. In in over a thousand statues in the comprised inventory of Philadelphia. Right. And yet very few countervailing ones. Right? And so Octavius Catto, that was only what? In 2018! That came out on onto the apron of City Hall. The first full figure, officially sanctioned African-American statute.

So, which is shameful, right? So that’s part of the problem of the permanence of monuments is that it’s overdetermined by lack of countervailing, uh, uh, monuments.

Karyn Olivier: Totally agree. Totally agree. Well that I don’t, you know, I said this last night at the Charles Library talk, like, we’re playing catch up. You know, like, okay! Former slave saves Stenhouse let’s make ’em! And I get the necessity, but I do wonder I’m not trying to fall into that same… I feel as it has to be multiple ways, we engage this. Education, monuments, performance, activation, just small gestures could have multiple meanings. I mean, I feel as though we’re relying on that… There’s too much reliance on what that has meant historically and we’re still buying into what into that.

Ken Lum: Yeah.

Karyn Olivier: But it needs to sit in, it has to engage us in different platforms and ways.

Ken Lum: Yeah. I agree with that and also I think, you know, is, is removal of a problematic statue, uh, you know, the settlement of a problem such as racism? The racism is still there, once, even if you remove it, right? So it might quell, a kind of energy and kind of anxiety and a kind of wish fulfillment to remove it because, you know, people it’s so poor and so kind of, you know, repugnant a presence, let’s say the Rizzo statue and so on… But does that mean that racism, and the police violence, particularly against African-Americans goes, goes away? Right? So, you know, the solution is, has to be more holistic than just simply removal of statues

Karyn Olivier: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Olivia F. Menta: Thinking collectively, I think this is a really great time for us to open up the dialogue to all the participants here tonight. We’ve got a good, good, almost 40 people, which is incredible. Thank you all for coming tonight. Um, I want to start off with a question from Patrick, one of our, um, auction committee volunteers, a valuable, valuable member of our staff.

Um, he asks: There’s a certain finality to visual art, even if it is open to interpretation by the viewer. How do you design a public work of art to ask a question, but not impose an answer point of view?

Ken Lum: Well, Karyn, you’re doing that with the-

Karyn Olivier: Yeah. I have a project right now. That’s literally- that’s the charge.

I can just describe it briefly. I mean, it’s, you know, Dinah was the former slave at the Stenton house. Um, and during the revolutionary war, um, they were kind of burning down the house in that area. Uh, they come to, they come in as tell her, “Gather your things, we’re about to burn your house down. Where’s your hay?”

And she’s like, “Go to the barn and get the hay!” The police come. And they’re like, “Are there any desserters?” It’s she’s like, “Yes, the desserters are in the barn!” So she saves Stenton house. So for years and years, although there was a plaque on the grounds. Um, and of course the plaque is, was a big deal at the time, because at that time there were, I think there were no, um, commemorations to any black women.

But when you read the plaque, it’s literally just about her saving, Stenton house. So this Memorial, I kept, I said, “What am I going to make? There’s nothing. We don’t know her last name. We don’t know when she was born.” Like there was no nothing. So I kept asking questions. So in the end I’m making this kind of, um, I have to use, so make it like, almost like a, a silhouette portrait- imagined portrait- of her.

And on each side there could be 10 key questions. And one side of the questions are, as if you’re asking Dinah, like “Where were you born?” “How did freedom feel?” “How would you wish to remembered?” “Did you ever have..” “What was your.. .the best part of your day?” And this is the question that someone, um, a community member said, “Did you ever wish you’d let it burn?”

So you had those questions and the other side is gonna be questions that she’s asking you, “Where were you born?” “What led you here?” “Do you feel free?” So my hope was that you could be having this internal questioning for yourself. You could be imagining her position. Maybe it’s a class it’s asking each other, these questions.

So that was my way up. I it’s no answer, like all those questions could not be answered because certain things are being discovered. I just found out recently that the site where we’re putting it is actually where we think she’s buried. So that’s kind of a surprising thing that happened. But my hope is that maybe things could be revealed about her over, over the years.

While my questions are kind of like the, what ifs. The imaginings of a, of a, of a past, or what does it mean to ask these questions that you’re asking of yourself to? How do I want to be remembered? So that was like my attempt to kind of not… I know initially they just wanted a sculpture. And the way now they’ve gone to the, budget’s kind of got crazy.

I’m like, I don’t want to have a sculpture that someone just walks around. Like, that’s not, I don’t know what to do with that. Like that becomes too finite, even though I do try, like in the Monument Lab to make the sculptures not sit still, to me, it just seemed to be more important that, I’m engaging a person that we know so little about, that it’s just a site for us to ask questions and to ask questions. About what is this moment now? How different are we now than we were then? So, yeah, I’m really into trying to do that. The questions.

Ken Lum: Right. And with respect to Patrick’s question. I don’t really agree with the premise because I think a very good public art, um, do open up questions.

And they become embraced by the public precisely because of the intrigue, in terms of the production of questions, they don’t necessarily impose an answer. There is a narrative, there is a tendency and that’s put forward, but really good works of ours- public works… You think of it, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, I think of Rachel Whiteread’s, uh, you know, uh, Jewish library in Vienna.

There’s lots of, uh, instances I can say.

Karyn Olivier: Yeah. And if it’s not doing that, it’s bad art. Any art, public, or not.

Ken Lum: There is bad art in the world, that happens sometimes.

Karyn Olivier: Yeah. Yeah.

Jacque Liu: Um, this is great. Uh, moving to another audience question.

Karyn Olivier: Can the person ask the question?

Jacque Liu: Oh yeah, you guys want to do it? We’ll just go in order if you guys want. Or, whoever wants to do it,

Olivia F. Menta: I nominate Morgan. Morgan, go!

Morgan Nitz: Hey,

Karyn Olivier: Hey!

Morgan Nitz: How are you all?

Karyn Olivier: Aw, it’s always such a joy to see your face.

Morgan Nitz: [Laughter] Oh, sorry. There’s a motorcycle going by outside. Um, So my question was from a question from what you guys were talking about a while ago, but I actually sent it privately to Patrick.

Um, so how do we stop the cycle of artists and artists, communities being used- especially in Philadelphia- as chess pieces in the process of harmful urban development?

And Karyn, you had said, you said something about rejecting, uh beautiful, beautification public art projects. And do you think that in certain cases, depending on the neighborhood, this is a way of protesting this? The urban development, by not putting maybe like a, um, a tourist attraction in a certain neighborhood that we could then make, come in and get developed?

Karyn Olivier: I think so. I think I would love for artists to trust. That they’re, that what they want matters. It could happen, or, or I remember being proposed. I was proposed, I started a proposal. I was asked to turn in proposal for a mural, and it was not your traditional, mural, it was kind of, and they encouraged me, but in the end they didn’t take it.

And they went with the one. I mean, it’s a beautiful, it’s nice. But it’s like, this is not what my neighborhood needs to see in Germantown. Back the stores back when it wasn’t a black neighborhood. I don’t know if that’s, I don’t know. That’s the thing we want to see, the reminder of when it was like, a good neighbor, when it was successful, you know?

And so that was a case where there was, it was almost an opportunity to do something else. It didn’t happen, but we can say “no.” Why don’t I feel like artists could be doing more like guerilla things. I mean, I have some students who just do things out in the world. They’re not as. Professional artists to think about like the money thing, but they’re putting work out there and I’m like, you did what?

I feel like we have space, but it’s okay to say, “no, I’m not going to participate.” And some of say, “How can you say that Karyn, you’ve got a teaching gig. You’re set up.” I’m like, I have a teaching gig, but it’s not like I’m making money. Maybe I will soon with Tonya. We’ll see what happens, but you know what I mean?

Like we, we don’t have to fall into that.

Ken Lum: Well, I mean, Morgan, I think was your question is really about the instrumentality of, of the artists, right? Instrument, becoming an instrument of private developers and, and the kind of, uh, administrative functioning of public art within the realm of city hall in, in partnership with, with, with development and planning and so on.

And that is, that is a problem. Uh, I, I wrote about that, uh, several essays. You could just get my book. There’s a chapter on that precisely can buy it on Amazon. Right. But, um, no, but no, but just to further what Karyn’s saying, there’s all kinds of artists, right? You’re always gonna, you’re going to get the professional public artists and they aim to please, right.

They, when I say, please, aim to please some popular idea of what public art should be, and how it should perform, in line with the architect, landscape architect, and the development. Right. And, uh, and they can have a very successful career that way. Right. And many people may even like it. They go, wow, there’s interactive.

It’s kind of fun. And, and that’s the only demand they place of art because that’s the only ambition they claim for her. Right. So. You know, how can we stop it? I don’t think we can stop it unless you have a police state. Right. So that’s just the way it is. But me as an indi, individual artist, I’m like Karyn, I would weigh those questions.

Am I interested in participating in this, in this project where, you know, people become, became displaced? So, you know, just for an opportunity for my art so I can make some money? I I’ve consistency at least said no in my career,

Morgan Nitz: But it’s not just about projects. Cause you know, I’m not getting approached to…. To do any public projects, but choosing where maybe your studio space is. You know? A lot of the affordable studio spaces for artists who are working in a service industry, or- you know, the art world doesn’t always have a lot of money to offer- they’re in Kensington, um, or in Southwest Philadelphia.

Ken Lum: Right. You’re talking about gentrification, how the artists are usually in the avant garde of that, I’ll be as a kind of precursor generation of. Of inhabitants prior to gentrification taking place, but they do all the kind of heavy lifting before gentrification takes place. And then when, when gentrification takes place, they can’t afford to live in the neighborhood that they actually help to improve.

Right. That that’s, that is a hornet’s nest, that’s for sure.

Karyn Olivier: Yeah. You look at, you know, Theaster Gates. I remember him saying at some point. His neighbors were like, wait, you’re raising the value. Like I, I now can’t afford to buy.. .Like he was first saying we all need to buy up our property and do these things. And he’s like, wait now, because of your status and the whole project now I don’t have access.

So it’s a tricky, it’s definitely a tricky thing. That’s no denying. But I think when I’ve looked at examples where artists have done, maybe they just, someone like Mark Bradford, you know, rock star, you know, he built like, you know, there’s, there’s like. The center for things to happen. Lauren Helmsley and South, South central, she has, she’s like, “I’m making money. I’m making a rec center. I’m staying in my neighborhoods. I want you guys to stay there.” There are examples where it’s happening in Germantown. There, people are stick there, people, or there’s enough of a community of folks who are committed to staying in the artists are recognizing who they are and working in partnership.

I’m seeing that more. I’m getting a little nervous cause people are coming now to my neighborhood. More, but, but there is a thing of, they’re enough people aren’t going anywhere, you know? So I think it’s, it’s a tricky one. Cause artists are, we’re the worst in a lot of ways.

Ken Lum: But it’s also important to take an international perspective and recognize that the prevailing model of real estate development is, is very particularly American here. Where you have an overdetermined, um, faith in the exchange of property and money. It’s not it’s stock, but you know, European societies are aren’t capitalists, but they have much stronger countervailing, uh, rules in terms of development that, and strong and stronger rules to protect tenants. And so on much stronger than, than here, right. And also public art processes have more, much more comprehensive engagement with the public and and, and so on. But here it’s like the power of the private developer just through the tax code is unbelievable.

Jacque Liu: I’ve seen a couple of questions here in the chat from Blaise and Virginia. Would you be so brave as to, uh, ask her question?

Virginia Maksymowicz: Just un-muted well, I first posted the question to the speakers, uh,

“Other than creating monuments, what are some other models for socially concerned artists”

And I have some ideas, but…

Karyn Olivier: Let’s hear, I want to hear yours!

Virginia Maksymowicz: Well, I’m, I’m actually thinking back a bit to history, but it. There’s a really good summary. I don’t know if you guys have read, um, the position paper that Clay Lord for “Americans for the Arts” put together and he released it on labor day about employing artists to work in communities. And he refers back to the WPA that everybody knows about, but he also refers back to CETA, in the 1970s and the two of us were on CETA.

And then he also talks about using, uh, programs that are in existence in existence now, like AmeriCorps and, and have an artist core of AmeriCorps. And the, the thing with that with communities is that basically artists sort of. Don’t go into a community and offer services. A developer’s not asking for the artists. A community asks for an artist.

So that relationship gets set on the community’s terms. Not that it’s easy, but it’s a different model. And the artist doesn’t get paid for the artwork. The artist gets paid a salary, and of course that relies on some sort of funding. Um, but if you haven’t seen the American for the Arts paper…

Karyn Olivier: Can that go in the chat?

Virginia Maksymowicz: I’ll go look up the Lincoln.

Ken Lum: Okay. I did read it because I participate. I’m a member of “Americans for the Arts” and gave a talk last year for the “Americans for the Arts”. Right. And I think that’s a great model and it’s a great history. Right? Um, but we, it has been, you know, more than half a century since Ronald Reagan. Right. And, and, and things have, you know, even to move half an inch towards that would be B you’re being accused of being a socialist, uh, yeah. You know, and so on. And then those side, all the kind of. You know, anti-capitalist murals that came up in the 1930s and you know, it’s like, no end of it,

Blaise Tobias: Ken, but Ken, this is a moment when obviously…

Ken Lum: I agree with you. I agree.

Blaise Tobias: We’re gunna need to recover from the devastation of the arts. And It’s an opening and one way that it’s palatable. I mean, it was signed into law by Richard Nixon. Yeah, a little prior to Reagan, but it’s a, it’s an employment program. It puts artists to work. They are, they are accountable for their work. They are, they are accountable to the communities

Virginia Maksymowicz: They were designed for artists. the jobs.

Ken Lum: I’m gonna add that, uh, that, you know, if the present leadership is evicted, Right then possibly that could come into place. Right? And, and I think the next administration, hopefully it’s not the same one, but the next new administration, has a glorious opening to really rethink. Um, you know, uh, society in terms of, for the greater good, right. Including how art can play a role role in that. But I’m just reciting, like the past 60 years has been a territorialzation.

Right? Um, Um, know ideological territorialzations, of being claimed by a very conservative ideology that have no support for people because it engenders weakness, and it’s a sign of weakness and, and, and that poor people. Other people, is necessary because that’s the collateral damage we must exist- that we must accept in order to have a product, a creative productivity drive the nation forward.

I mean, that’s the, that’s the very pernicious narrative.

Blaise Tobias: Right. But Ken the point is, All right, it was 40 years ago, not 60, and just, you know, the point is to reclaim possibility. Right?

Ken Lum: I know. I understand that

Blaise Tobias: It is so mind boggling to any young person today. That around the, you know, the late 1970s, 10,000 artists were employed around the United States, typically at a salary, that if you convert it to current dollars, is about $40,000 a year with health benefits and vacation. Right? I mean, young people just don’t believe it! Because

Ken Lum: It’s not that they don’t believe it, the issue is not rationality, the issue is, is ideology. That’s the problem.

Virginia Maksymowicz: And before I sign off, it doesn’t necessarily have to be government funding. I don’t know if any of, you know, Rachel Chanoff who runs this organization called “The Office,” but it’s an arts advocacy group that actually raises money.

And she’s involved in a project with museums in the Berkshires, where they’ve raised private money, but not as grants to artists. Private money to hire artists to work in communities. So it is a model.

Olivia F. Menta: Such an awesome dialogue! Thank you so much, Blaise and Virginia, and Ken and Karyn. We have time for one more question. So I want to um.. Stephanie Fuentes, you wanna uh, ask your question?

Stephanie Fuentes: Hello, can you hear me?

Olivia F. Menta: Yes!

Stephanie Fuentes: Um, wonderful. So I’ve been on the side as an administrator, and I want to ask you as artists, um, you know, for having to create work for public spaces…

What do you want from administrators, from city planners, to know, or to do, in order to help you create your best work?

Jacque Liu: As disclaimer, be careful. Cause that’s what I was doing until Mayor Kenney shut down the office. And Stephanie too,

Ken Lum: Well, I mean, I could give the story of when we first did the first iteration of monument lab, not the 2017 one, but the 2015 one with Terry Atkins. And um, we went to City Hall. We got a $600,000 grant from, uh, um, And we were no $350,000 grant.

And we were to, um, you know, do a kind of small scale one for the courtyard City Hall. We went to city hall. We asked one person in this office and they’d say, “We don’t know no who we should direct you to.” I’m not talking about Jacque and that office, I’m talking about. No, I’m talking about engineer, all kinds of other people we were supposed to…

And there would be people in city hall that didn’t know. Who to see in another wing of city hall, and then someone says, “Well, you should-” and one name was referred over and over again. And then I said, “Okay, which office?” And then one person, “I’ve been here like 20 years, I’ve never met the guy.” “Okay. And you’re referring to, that I go see this person, but you’ve never met this person.” Right. So that’s one endemic problem at City Hall.

And then the other problem was when we tried to set up the Terry Atkins in the courtyard of the City Hall, a lot of, not, not Jacque. There were a lot of people in city hall. “You can’t do that,” right? Because “you can’t set up something there.”

And “You can’t ask us, as you have asked, to extend the opening hours of the courtyard,” because they used to lock the, those ugly Gates before the new Gates at about six o’clock. Right. “We can’t, we have to lock it” and we’d say, “Well, why?” “You don’t know Philadelphia. You don’t know Philadelphians. They would be hanging around.”

I said, “that’s the whole point! We want them to hang around the courtyard, the most symbolic space in the city.” Thank God, someone, I can’t remember who it is. Some Paul Farber would remember someone said, “let’s just maybe give it a try. We’ve we were, maybe this is maybe they’re right. Maybe this is an old mindset we’ve had about Philadelphia and, um, being, you know, just all animals or whatever.”

And, uh, and so they, they opened it up, right? So we feel that we opened up space center, uh, you know, the old, uh, court courtyard of City Hall. We produced space in, in, in fact, right. So I would say, you know, they should do their business, but they should also be receptive and open to all kinds of possibilities in terms of, uh, In terms of, you know, living, living the reality of the city. My sense was that many of the planners and so on had this conceived notion of the city, but didn’t have any lived notion of the city.

Olivia F. Menta: Karyn, any final words?

Karyn Olivier: Um, listen to artists.

Jacque Liu: Well, um, to close out. I want to say first, um, not all city folks are that bad. A lot of them are, but that’s the, but otherwise I have a lot of, um, a lot of thank you’s, honestly. Um, thank you, Karyn and Ken for being here, you are both amazing, uh, thinkers. Your work is so important and then it really helps to shape, um, make a positive impact in their communities.

Um, thank you to our audience for being here and for your support of Artblog, Artblog is truly a pillar in the community. Let’s give it up for artblog here.

[Applause]

Thank you to my fellow board members who are on this call and just those not also board. The board is amazing. Uh, Roberta and Morgan do an amazing job of stewarding us throughout all of this. Um, it’s great fun. And lastly, Roberta and Libby, I see you’re both on the call here. You know, like the co-founders of this, I think of it as an artist project, you know, of this ongoing artist project that I cannot believe is 17 years old now.

Um, do you have any last words that you’d like to say either of you?

Ken Lum: You mean Roberta and Libby?

Jacque Liu: Yeah, Roberta and Libby.

Roberta Fallon: Can you hear me? I just unmuted myself, but I don’t know if you heard. Oh, okay. I’ve got a thumbs up. Um, well I would echo yes, everything is relevant. There’s a podcast on Artblog talking about it. Go to artblog. Look for Ken Lum. It’ll come up and then go.

There’s link to buy his book, the buy the book. It’s great. All right. I guess that’s my final words. Go to Artblog. You’ll find it all there. Everything you ever wanted about art is on Artblog. And thank you to all for coming. Thank you to Libby. For being my compatriot for many, many years, setting up Artblog and running Artblog and having a wild and crazy and wonderful time.

Jacque Liu: Good night, everybody.

Ken Lum: Thanks everybody.

Karyn Olivier: Thanks so much. Take care.