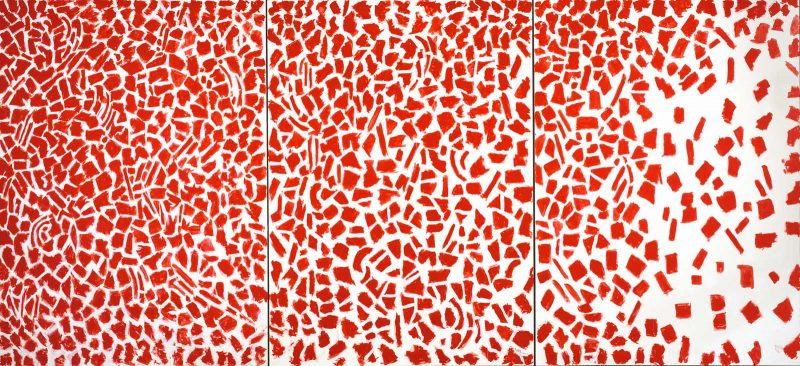

This stunning catalog and the exhibition that spawned it were designed with dual aims: to bring the work of a significant artist, Alma Thomas (1891-1978), to much wider attention, and to complicate and hence deepen the understanding of her life and work. Most people who know of Thomas are aware of the one-line biography that has commonly circulated: a junior high school teacher who took up art in her retirement and received national attention for her abstract paintings in her seventies. This misleading story implies that she was a self-taught artist who, had she appeared on “What’s my line?” would certainly have stumped all the panelists.

The actual story of Thomas’ life and artistic development is considerably more interesting and the catalog rounds it out in many dimensions. Thomas had an unusual background for an African American from the South. Her maternal grandfather was born into slavery but acquired sufficient land to run a large farm, hire outside labor and put his ten children through college at nearby Tuskegee Institute. College-educated African Americans had an enormous respect for education and a commitment to help the less-fortunate; this resulted in many turning to teaching, a profession which guaranteed a significant social position. The nine aunts and uncles on her mother’s side all taught at one time or another. Her parents were the only African Americans to purchase a home in a suburban neighborhood of Columbus, Georgia where her father was a businessman. Their household in Columbus and later in D.C. emphasized the values of learning and the fine arts through culture clubs and reading circles modeled on the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle, civic clubs devoted to community service and a variety of private classes in art and music.

A fiercely independent woman, Alma Thomas attended Howard University at age thirty and was the first graduate of the art department. She received a master’s degree in art education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, later studied painting at American University, and took private lessons with one of her professors, Jacob Kainen. She was often older than her teachers, but she always had a clear sense of her role as an artist. She traveled to extend her knowledge; the book includes photographs of Thomas at the Century of Progress fair in Chicago (1933) and on a Study Abroad trip to Europe. She maintained connection with various mentors and actively kept up with the art world via periodicals, books, and visits to museums. Thomas participated in D.C.’s white and Black art communities, including helping to establish the Barnett Aden Gallery which exhibited progressive art across color lines.

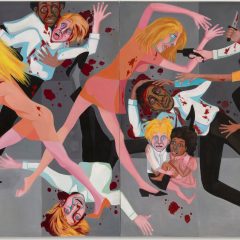

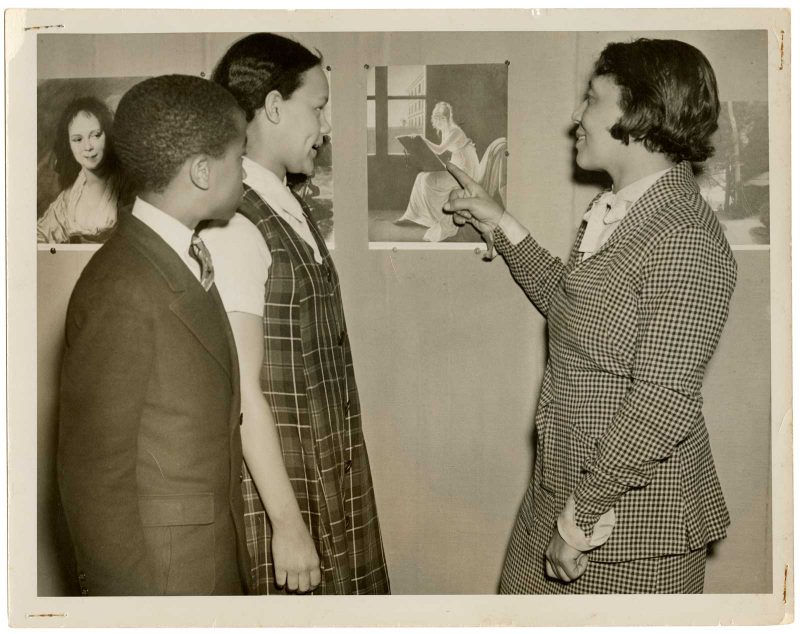

When discussing art, her own or others’, Alma Thomas always invoked beauty; it was her touchstone and clearly had a transcendental value for Thomas beyond aesthetics. Beauty was the focus of her teaching at Shaw Junior High School and at classes she taught at a nearby church for neighborhood children. She emphasized the abstract values of beauty and art to students in an impoverished community to show them broader possibilities than daily subsistence. She encouraged them to see beauty as a resource that they could bring into their own lives. The political aspect of Thomas’ work was not in subject matter, as favored by the Black Arts Movement; it was the conviction that beauty and art belonged in the lives of African Americans and her lifelong art teaching reflected a political dedication to her people. The decision to pursue abstraction was also a political expression for an African American woman. While she believed that her artistic values transcended race, time and nationality, her confidence that she could participate equally in an otherwise white, male community of painters claimed agency as a political stance.

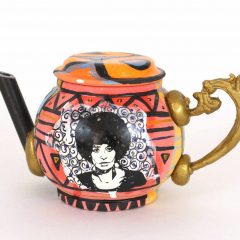

Alma Thomas had broad interests which included gardening – the garden at her home and visits to public gardens were an acknowledged inspiration for her paintings; puppetry, which she studied and included in her teaching; fashion, as indicated by the dresses she commissioned for her exhibition openings; modern design, as demonstrated by a Saarinen chair from her home; space exploration, which inspired a series of paintings; and music, from the latest teen dance music to opera – all of which she played while she painted in her studio, situated in her kitchen.

Seventeen specialists were assembled to contribute to the catalogue. They include curators, conservators, artists, a poet, and scholars of art history, anthropology, Africana studies, American studies, visual culture, and American history. Some of them wear more than one hat, as had Thomas. That the catalog’s writing is consistently clear and free of jargon is a tribute to the authors and editors. The essays are illustrated with a wealth of photographs and archival material that document the artist’s life. The full-color illustrations of the artworks are superb. The catalog includes a map of significant D.C. locations in the artist’s life and an index.

Seth Feman and Jonathan Frederick Walz, eds. “Alma H. Thomas; Everything is Beautiful” (The Columbus Museum of Art and Chrysler Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press; Columbus, GA, Richmond, VA and New Haven: 2021) ISBN 978-0-300-25893-6.

$68 — Yale University Press; Barnes & Noble

The exhibition, “Alma Thomas; Everything is Beautiful” is at the Chrysler Museum of Art through Oct. 3, 2021, then travels to The Phillips Collection, Oct. 31, 2021- Jan. 23, 2022, Frist Art Museum Feb. 25 – June 5, 2022, and The Columbus Museum July 1 – Sept. 25, 2022.

Jan van Raay, Portland, OR. This exhibition is co-organized by the Chrysler Museum of Art and The Columbus Museum, Georgia.