Bo Bartlett’s paintings represent Academy style to the nth degree. So it has come to pass that the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts is right now exhibiting “Heartland,” a show of more than 40 works by this favorite son (image, “Heartland”), that has the feeling of Norman Rockwell and the pigtailed, freckled blond on the Kellogg’s cornflakes box.

Bo Bartlett’s paintings represent Academy style to the nth degree. So it has come to pass that the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts is right now exhibiting “Heartland,” a show of more than 40 works by this favorite son (image, “Heartland”), that has the feeling of Norman Rockwell and the pigtailed, freckled blond on the Kellogg’s cornflakes box.

The paintings are mostly huge things, unfit for any of the walls in my little ol’ house, all painted beautifully. They aspire, with their size, to say something big. And some of them do. But many of them are just oversized.

Rituals

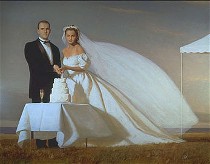

Given the religious themes of his paintings, it’s no surprise that so many of his paintings are of rituals–the school reenactment of the three wisemen spotting the star in the East, weddings (and weddings and weddings), a female Christ post crucifixion, the obligatory snapshot after the Homecoming game of the three power couples on campus in front of the bonfire (image, “The Wedding”).

Given the religious themes of his paintings, it’s no surprise that so many of his paintings are of rituals–the school reenactment of the three wisemen spotting the star in the East, weddings (and weddings and weddings), a female Christ post crucifixion, the obligatory snapshot after the Homecoming game of the three power couples on campus in front of the bonfire (image, “The Wedding”).Of that group of paintings, the school reenactment, which has a Norman Rockwell air of description and down-home folks, seems the least silly of the scenarios. It’s pretty straightforward, and the children and their teacher, caught glancing one way or another, provide an image of a classic American experience through specific kids and a specific teacher.

Snapshots

That snapshot quality of moments frozen in time, glances and facial expressions trapped in the moment of a shutter snapping, also carries along “The Box,” a picture of children dressing up in war memoribilia stored in a wooden box, and also carries “Sightland,” in which a father takes aim with his rifle somewhere in the distance while the son’s focus is on the artist or picture taker. I liked the modesty and reality of the storytelling in these two. They are bits of Americana.

That snapshot quality of moments frozen in time, glances and facial expressions trapped in the moment of a shutter snapping, also carries along “The Box,” a picture of children dressing up in war memoribilia stored in a wooden box, and also carries “Sightland,” in which a father takes aim with his rifle somewhere in the distance while the son’s focus is on the artist or picture taker. I liked the modesty and reality of the storytelling in these two. They are bits of Americana.

Religion lost

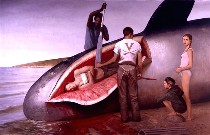

But while Bartlett seems to want to be the Rembrandt and Caravaggio of the American story–the land, the culture, the ideals, the myths–he lacks the backstory of the Bible that Rembrandt and Caravaggio had as a cultural commonplace. Everyone knew back then on viewing a painting of Jesus coming down from the cross just what had happened. But what does it mean when a young woman is coming down from the cross? What does Bartlett’s “Leviathan” mean? I don’t know who this Jonah really is or why he’s washed up on the coast posing on the all-too-real innards of the whale(image “Leviathan”). It just seems pretentious.

But while Bartlett seems to want to be the Rembrandt and Caravaggio of the American story–the land, the culture, the ideals, the myths–he lacks the backstory of the Bible that Rembrandt and Caravaggio had as a cultural commonplace. Everyone knew back then on viewing a painting of Jesus coming down from the cross just what had happened. But what does it mean when a young woman is coming down from the cross? What does Bartlett’s “Leviathan” mean? I don’t know who this Jonah really is or why he’s washed up on the coast posing on the all-too-real innards of the whale(image “Leviathan”). It just seems pretentious.

So do “Dreamland” and “The Bone,” which also have a histrionic quality. “The Bone” just seems pumped up, the bone obviously a symbol of who knows what; and “Dreamland” has too many characters, too many costumes, too many ideas all painted too seriously. Fellini did the human comedy parade with a lighter touch (image left, “Dreamland”).

So do “Dreamland” and “The Bone,” which also have a histrionic quality. “The Bone” just seems pumped up, the bone obviously a symbol of who knows what; and “Dreamland” has too many characters, too many costumes, too many ideas all painted too seriously. Fellini did the human comedy parade with a lighter touch (image left, “Dreamland”).

In “Homecoming,” the looming effigy of the devil, the two men looking away, the young boy, the three cheerleaders, the intense sunset sky, the convertible car, all seem to overwhelm the basic ritual, which stands quite nicely by itself. The painting is a kind of religious triptych, the three couples surrounded on each wing by three outsiders. But it’s without the backing of the religious meaning and without the focus of one clear subject.

In “Homecoming,” the looming effigy of the devil, the two men looking away, the young boy, the three cheerleaders, the intense sunset sky, the convertible car, all seem to overwhelm the basic ritual, which stands quite nicely by itself. The painting is a kind of religious triptych, the three couples surrounded on each wing by three outsiders. But it’s without the backing of the religious meaning and without the focus of one clear subject.

Humor helps

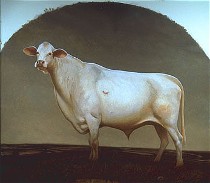

The Rockwellian caricature that works in the school play also contributes to the “Listeners,” a picture of three blind men on a hay cart, their red-tipped canes dowsing like insect antennae for what’s around them. The humor undercuts the otherwise ponderous big theme of humanity trying to listen for its place in the universe. The heroic cow icon in “The Calling” is leavened by its ridiculousness–without losing its meaning.

The Rockwellian caricature that works in the school play also contributes to the “Listeners,” a picture of three blind men on a hay cart, their red-tipped canes dowsing like insect antennae for what’s around them. The humor undercuts the otherwise ponderous big theme of humanity trying to listen for its place in the universe. The heroic cow icon in “The Calling” is leavened by its ridiculousness–without losing its meaning.

(The talismans encased in the frames like the windows in African nkisi figures–the cow’s horn, the deer skin, the twigs in “The Calling,” “Young Life,” and “Heartland” respectively seem like too small a gesture for the competing canvas and frame.)

Specific details

“Painters Crossing,” shows Bartlett’s mentor Andrew Wyeth, standing close to his wife, Betsy, with model Helga Testorf standing apart behind them. The painting is provocative, the composition, with its rich furs and quoted landscape expresses wealth, privilege, success, inclusion and exclusion–not to mention a salute to Wyeth’s paintings. The story is well-known enough to be accessible.

“Painters Crossing,” shows Bartlett’s mentor Andrew Wyeth, standing close to his wife, Betsy, with model Helga Testorf standing apart behind them. The painting is provocative, the composition, with its rich furs and quoted landscape expresses wealth, privilege, success, inclusion and exclusion–not to mention a salute to Wyeth’s paintings. The story is well-known enough to be accessible.

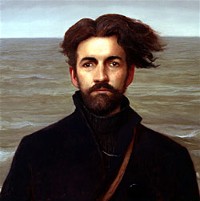

Other portraits that seemed especially good were “Ishmael” (above right) and of “Parents” (left) I love the way his mother closed her eyes in weary sufferance, and the way his father put his hands in his pockets, an expression of casual-seeming power–just one of the good ol’ boys. Meanwhile, they’re turned away from one another. “Ishmael,” with his pea coat and wind-whipped hair has a timeless look that situates him in Flemish portraits of the 15th century, in “Moby Dick” and in the here and now.

Other portraits that seemed especially good were “Ishmael” (above right) and of “Parents” (left) I love the way his mother closed her eyes in weary sufferance, and the way his father put his hands in his pockets, an expression of casual-seeming power–just one of the good ol’ boys. Meanwhile, they’re turned away from one another. “Ishmael,” with his pea coat and wind-whipped hair has a timeless look that situates him in Flemish portraits of the 15th century, in “Moby Dick” and in the here and now.

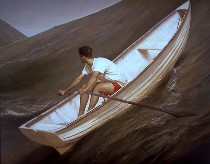

Another simple success is “Lifeboat.” The meaning is clear enough and the image, with its lost horizon and vertiginous waves, the wedding ring on a chain around the rowers neck, put me back into the existential boat in the waves in “The Triplets of Belleville.”

Another simple success is “Lifeboat.” The meaning is clear enough and the image, with its lost horizon and vertiginous waves, the wedding ring on a chain around the rowers neck, put me back into the existential boat in the waves in “The Triplets of Belleville.”

I suppose what I’m saying is that the simpler Bartlett gets, the better he gets. The successes are individual and idiosyncratic enough to feel grounded in the kind of realistic painting he does so well. When he adds elements that feel too unrealistic, the story slips out of his grasp–and mine.