I’ve always had a special place in my heart for quirky work outside the mainstream. So when the husband of artist Ann Irwin asked for an essay on Irwin for a book documenting his late wife’s work, I quickly said yes. A show of her work, Transmutation and Metamorphosis: The Collages of Ann Irwin, is opening July 9 at the Michener Museum, in Doylestown. The book, published in 2008, is a love note to an indomitable spirit, put together by husband Lester Roy Zipris, Irwin’s son Lucas Irwin (the author), and her friend book-designer Diane K. Becotte, three years after the artist died. Zipris, still in deep mourning, wanted to reinsert his wife’s work to its proper place in the art historical record. The book, Ann Irwin: Visionary Work, was the first step in that effort, and this exhibit is confirmation of what a wise first step it was. Ann Irwin died in 2005 of complications of complications. Here’s a slightly modified and shortened version of the essay:

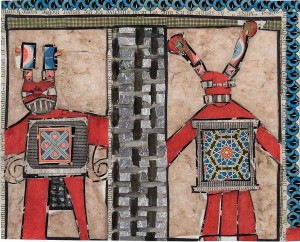

In Ann Irwin’s painted collages, houses sprout heads or rays or fire, hills and rugs bristle with Pez-dispenser stick figures, and trees grow ribs and skulls. Even though these transformations may seem threatening, they are instead optimistic. For nearly 30 years, Irwin harnessed their magical power, creating talismans for managing an unsafe world.

Irwin’s vision includes insider awareness as well as an admiration for visionary art, as does contemporary French artist Annette Messager, a trained artist whose diaristic work is strongly influenced by outsider work, specifically work she saw in Jean Dubuffet’s Collection de l’Art Brut. Irwin’s work has diary elements expressed not through words but through images.

Despite Irwin’s formal art training at Tyler School of Art outside Philadelphia, receiving a BFA in 1964, Irwin remained focused on her own vision. In a letter to exhibitions curator Joanne Cubbs at the John Michael Kohler Art Center, written before Kohler exhibited Irwin’s 1986 solo show, “Obsessive Image: the Collages of Anne Irwin,” she wrote:

The four years of schooling [at Tyler] had very little influence on my work. I was allowed to work independently and luckily received much encouragement. I do not consciously know the rules of composition, perspective, design, etc. (from an unpublished letter to Cubbs, 24 April 1986).

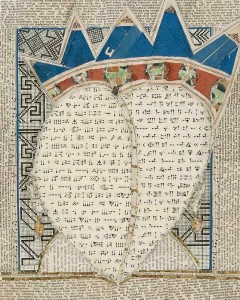

So Irwin chose a technique that matched her lack of interest in the rules of composition, perspective and design. Collage expresses flatness by its material reality; the edges and the shifts in materials compete with any sense of illusion. Irwin’s works are unapologetically flat, and include complex one-layer inlays of newspaper, directories, musical notes, foil candy wrappers, even cuneiform script, along with water paint media including gouache and acrylic, scraps of wood and bits of fabric at times, and occasionally a thickly applied gluey medium.

Many of the pieces have a decidedly fabric-like feel. And the black-and-white text and pattern tones that predominate link the work specifically to the somber Pennsylvania Dutch quilts of the region where she lived. Irwin sliced off pieces of letters, words, sentences and paragraphs. …She used paragraph blocks much the way a cartoonist lays in Benday dots or color.

Like outsider Cuban-born Jose Felipe Consalvos, who used cigar bands with abandon not only for their pattern and glitter, but to create a spiritual sense of wonder, Irwin used text and music for their magical properties–although the kind of spiritual magic she asked the notations to perform have nothing to do with Consalvos’ razzle-dazzle of Catholic psychedelia. Rather Irwin asked her paper and foil and twigs to function as a silent prayer, to anchor the dreamy images, to keep them real and material.

“Irwin’s collages and paintings possess a strong visionary quality,” wrote Cubbs in her essay for the Kohler show. Irwin made her art with urgency and persistence because it was her magic charm for survival in a life filled with dire health problems and emotional stress. The work was of ephemeral materials and her disregard for its survival–no record-keeping, as well–was much the way she coped with her own survival. After the 1973 birth of her second child, Lucas, she nearly died, hospitalized with colitis for six months. Shortly after, she was also diagnosed with a rare pulmonary disease plus other complications. During her illnesses, her first marriage fell apart. Devastated, she and her two young children moved to Bucks County, Pa., to live with her parents. The move was a critical event: It led to an apprenticeship at the Moravian Tile Works, where Irwin learned the clay design technique that inspired her to lay out her collage materials in one layer like tiles.

Although Irwin insisted her blocks of text were there only for visual texture, the choice of using words suggests they are an incantation, a sort of abracadabra, to effect the wishes expressed in Irwin’s work. Houses and sails are papered with words . An inscrutable heart/head is flecked with cuneiform wedges. Hills and gardens are covered with musical notation or Asian script.

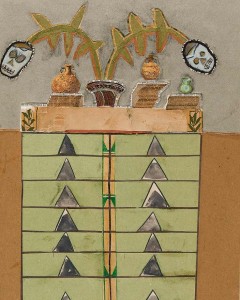

That abracadabra quality shows up in other ways as well. Irwin draws skulls inspired by Mexican folk art, totems and kachinas inspired by Native American art, juju sticks with heads, masks with alien eyes and bared teeth. Skulls grow from flower pots set atop chests of drawers. The homey chests echo the Arts and Crafts architecture and furniture that she loved and lived with. The chests two halves function as a couple, shoulder to shoulder, while the skull heads pull away from one another. The chest is the wish. The skulls are the fear.

Even when she was profoundly sick, her work remained relentlessly visionary and symbolic.

As her health deteriorated, she obsessively continued working, in her last years tethered to her oxygen with a 50-foot tube that enabled her to get around the house, her garden and her studio. Until several days before her death, her family would find her sitting up in bed, snipping bits of paper, her cheerful demeanor belying her terminal condition. She died of multiple organ failure in 2005 at the age of 62, leaving behind her nearly 400 pieces of art in the house, uncatalogued, untitled, unnumbered.

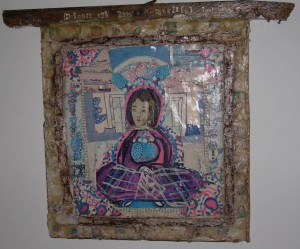

Irwin’s second (and third) husband Lester Roy Zipris–-they married twice — says she made only one piece that referred to her illness. That work, Madonna and her Bronchial Tree, shows a central figure sitting cross-legged, dressed in exotic pantaloons and gown and crowned with a street lined by houses and a pair of trees. She is painted, with a collaged sad face and painted spotted lungs or breasts. A disembodied man’s arm (he’s wearing a suit jacket) is trying to hold on to her. She is framed with little figures, some of whom also have lung problems; they are coated with a thick, gluey medium. Totems protect the madonna on either side. For all that, it is a relentlessly cheerful image. Above the little suburban landscape of houses with its compressed horizon line, boats ply rivers above which is a barn. The painting teems with the business of life.

Transmutation and Metamorphosis: The Collages of Ann Irwin

Michener Museum, Doylestown

July 6 – Oct. 16, 2011