Dancing Around the Bride at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA)through Jan. 21, 2013 is an extraordinary, multi-dimensional exploration of a significant period in American art history. While the ideas it presents are hardly new, the sensitive installation, designed by the artist, Philippe Parreno, emphasizes the multi-disciplinary nature of the mutual personal and artistic influences among Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. This is an exhibition as Gesamkunstwerk, and it offers the best, possible understanding of the interconnected, artistic experimentation in New York City in the late 1950s-1960s.

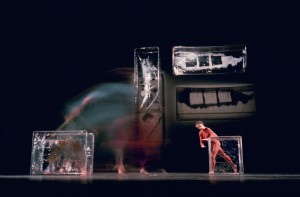

Parreno’s installation pivots around a low, platform stage in the middle of the gallery, on which former members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company will perform (to music by Cage), at designated times throughout the exhibition. Above the stage hang seven, transparent blocks, made of crinkly plastic. Each bears imagery that is a direct quotation from Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped bare by her Batchelors, Even (1915-23), known as The Large Glass, (on view in its usual room at the PMA). The suspended homage to Duchamp was Jasper Johns’ 1968 stage set for Walkaround Time, a dance by Cunningham. Johns was the artistic advisor for Cunningham’s company from 1967 to 1980, a role Rauschenberg had played from 1954 to 1964.

The chance to see the dancers, the last to be trained by Cunningham, who left instructions to disband the company after his death, is not to be missed. They have the virtuosity and extraordinary precision Cunningham required, and this is an opportunity to be in unprecedented, intimate proximity to them. Cunningham’s choreography is based upon a precise vocabulary of movements, and is closer to ballet than to modern dance, especially dance that involves vernacular movement. I expect it will be performed by ballet companies, before long. The opportunity to see the dances surrounded by multiple works of Rauschenberg and Johns reinforces the interconnectedness of their work.

Parreno’s other contributions include bleachers next to the stage, where visitors can sit during the performances; various sounds and compositions by Cage, played throughout the galleries; window blinds that open and close at seemingly random intervals; changing lighting on the stage; and two grand pianos, altered according to Cage’s instructions, one next to the stage, the other in the great hall, at the foot of the stairs. Both are programed to play compositions by Cage.

The exhibition emphasizes a number of points: the use of chance as an element in generating compositions, and hence a rejection of traditional, formal methods of constructing musical scores, dances, and the visual arts – which should not be confused with improvisation in performance – Cage and Cunningham both used chance to generate scores and sometimes employed the I Ching to re-order the movements, but the scores were meant to be followed as strictly as those by Stravinsky and Balanchine; collaboration as a fertile source of artwork, even though each of the artists assumed individual credit for his contribution, and despite the fact that Cage and Cunningham’s collaborations intentionally involved developing the work independently of each other, then presenting it at the same time; and the significance of Duchamp’s The Large Glass for the four, younger artists. (See image of The Large Glass here.)

A theme that runs throughout the exhibition, although unacknowledged by the curators, is the function of a pre-Stonewall, gay, artistic community within which Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns developed their ideas. They were more than four friends and colleagues. They were two couples, Cage and Cunningham remaining partners for life, Rauschenberg and Johns splitting up in the early 60s. The artists dedicated and bestowed numerous works in the exhibition to each other – it is worth reading the labels carefully

The room housing The Large Glass (which will never be moved, as a consequence of its earlier mishap) and several areas outside it, have been re-hung for the exhibition, and the adjacent, small video gallery is showing two Charles Atlas films (as videos, I suspect) of Cunningham pieces. When approaching The Large Glass via the long corridor in the modern art wing, be sure to notice Isamu Noguchi’s Mirror (1944), sited about mid-way. It is based on a stage set that Noguchi created for the dancer, Martha Graham, in whose company Cunningham danced, before turning to his own choreography. Their collaboration represents the tradition against which Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns worked, represented in painting by Abstract Expressionism: the emphasis on grand gestures, heightened emotionalism, heroic individuality, and emphatic heterosexuality (Noguchi and Graham were lovers). Their response was art where chance replaced individual choice, small, repetitive actions replaced sweeping gestures (this is less true of Rauschenberg than of the others), and sexuality and emotion were deeply encoded behind seemingly-impersonal facades.

Throughout the exhibition works are paired to reveal both citations and parallel thoughts of the various artists. In a gallery largely devoted to chess (a passion of Duchamp during the last two decades of his life), Rauschenberg’s Music Box (Elemental Sculpture) (created after 1953, it is a small fetish piece consisting of a box, impaled throughout with nails, which contains a rock that makes noise when the box is moved) sits on a pedestal beside Duchamp’s With Hidden Noise (1916), the ball of string in which Duchamp had Walter Arensberg hide a never-to-be-named object, that makes sounds when the piece is manipulated. In the little vestibule space outside the video gallery is another Rauschenberg object, from 1995 – a ball of string with a ruler sitting atop it, an even clearer, formal reference to With Hidden Noise. It is just one indication that Duchamp’s influence on Rauschenberg extended long beyond those early years represented in Dancing Around the Bride.

In connection with the exhibition, the PMA is hosting an extensive program of dance and music performances, film screenings, and conversations, all of which are listed on the website. They have also partnered with Bowerbird on Cage: Beyond Silence, citywide celebration of the centennial of the composer’s birth, taking place at the museum and other venues across Philadelphia.