[Andrea enjoys a few chuckles at a show that asks viewers to re-examine the value of objects and material experiences, and also asks artists to obliterate their work after showing it only once. — the Artblog editors]

Saul Anton and Ethan Spigland curated the provocative, lively, and thoughtful exhibition Destroy, she said, on view at the Boiler, in Brooklyn, March 5 – April 5, 2015, on behalf of Pierogi . It coincided with the establishment of an online archive, the “Foundation for Destroyed Art,” where according to the announcement, “works of art will exist only in their documented destruction and spectral afterlife.” The curators’ instructions to the artists included the stipulation that the works expire with the exhibition, and not be shown again.

Destined for demolition

Purveyors of popular culture are well aware that destruction sells, and while it is an unusual aspect of the art world, it has a pedigree in work since the 1950s, including Robert Rauschenberg’s erased de Kooning drawing, Jean Tingley’s “Homage to New York,” the work of Raphael Montañez Ortiz, etc., and stems from a variety of motivations. These artists employed destruction as art, as opposed to the many more artists who run out of storage space and have to destroy old work to make room for the new. I remember some years ago, at a College Art Association meeting, someone was handing out cards for his business, which was destroying art for artists who couldn’t bring themselves to destroy their own. I never learned whether it was a joke or real; it was certainly plausible.

The selection at the Boiler was conceptually broad, diverse in format, and occasionally quite funny. Kate Teale was in the space when I visited, erasing a large drawing titled “White Out” from the rear wall of the gallery; the drawing represented a building largely obliterated by snowdrifts after a major storm. She titled its erasure “Destruction of White Out,” and told me she enjoyed my laughter as I went through the exhibition.

Entering the gallery, I had walked through debris which was all that remained of Bob and Roberta Smith’s “Destruction of Maps of Hope,” which consisted of three altered maps placed on the floor and shredded by foot traffic. Was the work suggesting that optimism is inevitably destroyed by interaction with others, or that dreams are destroyed by everyday reality? Behind it, taking advantage of the extreme height of the interior, was Ray Smith’s “Cradle,” which resembled a large seed breaking out of a pendant pod. Smith will destroy the sculpture at the end of the exhibition. While its grey, mottled surface resembled concrete, it was made of Styrofoam, which should make the job easier.

Pushing the limits of curator comfort

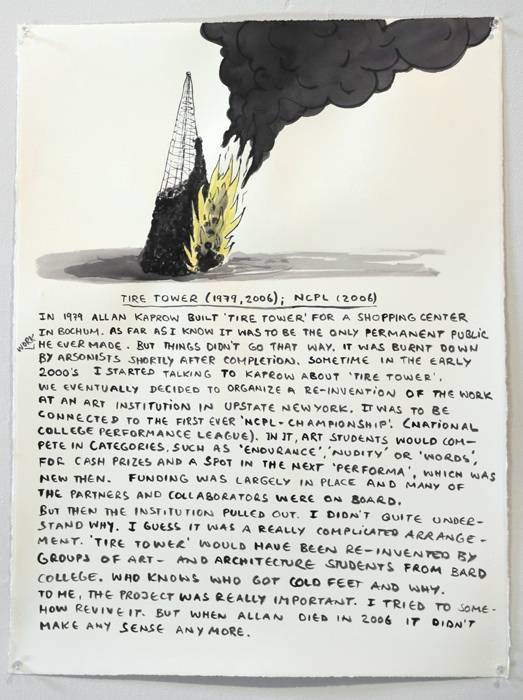

Olav Westphalen contributed drawings with text documenting the destruction of seven works of art due to surprisingly diverse circumstances, including re-use of materials, neglect, abandonment, and vandalism. His deadpan narratives and recycling of destruction as subject matter for new art was one of the reasons I was laughing. Hanging beside Westphalen’s works was another narrative piece: “Monument to the Unelected” by Nina Kachadourian. This time, the artist engaged a museum staff member in the act of destruction–something that goes against the strongest instincts of museum personnel. The work, consisting of a group of mock political signs that had been placed around the city, was acquired by the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art. As recorded in a video, one of the signs was found to contain a typo, so the artist replaced it and sent instructions that the faulty sign should be destroyed. If I laughed here, it was because in my experience as a curator, I found that contemporary artists regularly tested the conventional pieties of museum practice, and I could appreciate the quandary of the museum’s registrar.

On the opposite wall was another narrative, raising significant questions about what constitutes art and what keeps it alive. Ward Shelley inherited a work, “I Am a Hunger Artist,” made by his mother. His “Destruction of I Am a Hunger Artist” documented an internal meditation about his knowledge and hence memory of her art–which only he had seen–and the fact that the memory would inevitably die with him. It’s an idealist notion of art, and of destruction built into the life cycle. Sadly, he didn’t suggest another generation to whom he could pass on the memory.

A video by Beth Campbell showed the artist creating a detailed drawing, which was then subjected to a series of events that might be her worst nightmares: Coffee is spilled on it, and the drawing is used for origami, shredded, put in a blender, and jumped on by her giggling toddler. His periodic giggling as the video looped made a delightful soundtrack to the exhibition and, of course, provoked still more laughter!

Other artists and destruction-themed reading

The exhibition also included work by Jeff Gibson, Serban Ionesscu, Miranda Lichtenstein, Jeanine Oleson, Peter Rostovsky, and Dexter Sinister. Two recent books address the subject of destruction of art: Lost Art (Tate Publishing, London: 2013), ISBN 978 1 84976 140 6, which originated in an online exhibition; and the catalog Damage Control; Art and Destruction Since 1950 (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and Del Monico Books, Prestel Publishing, Munich: 2013), ISBN 978 3 7913 5316 6.

Destroy, she said was on view at the Boiler, of Pierogi Gallery, 177 N. 9th St. Brooklyn, NY, from March 5 – April 5, 2015.