“Stop fucking around and be a man.” It’s a well known line from the intro to Illmatic, a classic hip-hop album by rap artist Nas. It was sampled from a classic hip-hop movie Wild Style by Charlie Ahearn. Raymond, the main character and artist, gets an earful from his older brother about his trade, graffiti. It’s the thing that makes him little money and won’t get him out of the hood. It’s the early 80’s, and graffiti has already claimed its place–in parks, on public art, on bridges and subway trains. It’s an often forgotten element of hip-hop, birthed in its modern iteration by graffiti artist Darryl McCray a.k.a. Cornbread. I got to meet him at the James Oliver Gallery on Chestnut St., where he hosted a talk for his work in I am Here. I enjoyed it, but a part of me felt uneasy about it. Something wasn’t right.

From the street to the white cube

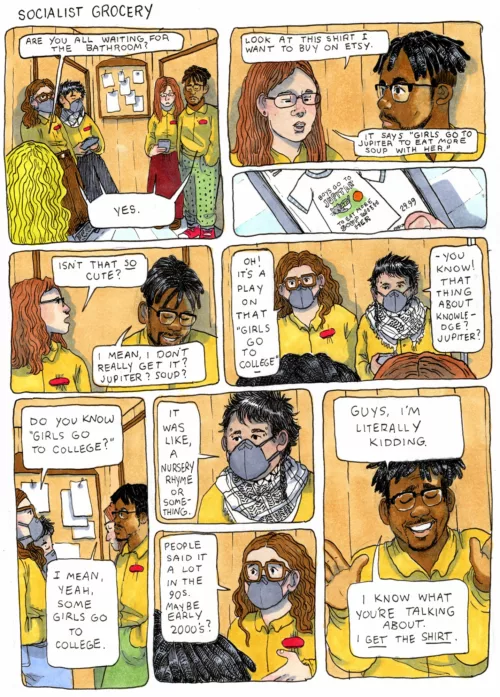

It’s the same feeling I have at the street art show All Big Letters in the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery. Is this supposed to be here? I drive through Bryn Mawr, a pretty suburb of Philly, to Haverford College. The campus is dumb-exquisite–the pond where geese float, the architecture, the students running, reading, and carrying on. A sweet black lady with freckles points me to the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, one floor up in the Whitehead Campus Center. There’s a sitting area with big a flat screen TV and books on graffiti just outside of the gallery. Someone is spray-painting and running on screen. It makes me think of Exit Through the Gift Shop, the documentary by street artist Banksy. All Big Letters is brilliant as an introduction to street art, and I think this is what it functions as best—a supplement to a class on street art. I feel weird, though, about seeing original stencils, spray cans—Red Devil, Krylon, Krink—and graffiti zines under a glass case. Steve Weinik’s photos seem like the only thing at home here in this white cube.

Even legendary street artist Basquiat a.k.a. SAMO channeled his street sensibility into Neo-expressionist art. He had borrowed from artists like Twombly to create something comparative to what the artists were doing then, what Keith Haring was doing then and so on. It’s kind of like what Chris Jehly and Nosego are doing now. But what I see here is like the story of Basquiat, a street artist laid to rest. I feel the same uneasiness Raymond felt in Wild Style when Fab 5 Freddy worked to get him notoriety beyond the streets. ‘Lee’ George Quinones a.k.a. Raymond a.k.a. Zoro in Wild Style has a piece in All Big Letters. “Howard the Duck,” his oil painting, a copy of piece he made in the streets, feels like an impaled head. From a formal standpoint and a street art standpoint, it doesn’t work for me. It’s the elements, the atmosphere missing. What I love is that it’s here for people who’ve never seen graffiti as anything beyond vandalism. A different setting can sometimes make the difference.

The people’s copy

But I say no. Go down to the dilapidated blocks in Nicetown, Kensington, Southwest, past Hakim, Mook, Black and Carlos, past Zakia and Malik through these alleyways and corridors of our union. Go to the train tracks, take the subway, take the A train, the Broad Street line, and look, really look. Have you been to Five Pointz in Queens? No? It’s gone now. Can you see the bubble letters nearly bursting at their seams, the twists and turns of our constrictions, a word, a trap now contorted into art? Take that, Times New Roman! Take that, Helvetica—Boom! Graffiti is the people’s copy: Over Six Billion Birthed. And the people will have their say, one way or the other.

I’m deep into my feelings as I leave. I get weak flipping through Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper’s Subway Art. It’s one of the books that sit outside of the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery on a coffee table. It’s the neighborhoods, the tags, the styles—styles, styles, styles for days. It’s ironic that the street artists community felt like a gated community then. I knew them, I knew their art, but it was shown and not talked about much, less than 1% of our conversations. Many people were familiar with it in a traditional way, as a community ill. The writing got there on facades, on public places somehow and something was being communicated, but most people didn’t understand what, only that it meant poverty.

Steve Weinik captures this in “Untitled (Potato),” one of his photographs in the show. A white truck with the word potato painted on it in black bubble letters turns left on a littered city street. This is after a rainstorm, a dirty puddle reflects it nearby. There’s discount shopping and unfinished road surface markings. The street itself is an amalgam of concrete and asphalt forced into each other. Two stories above a storefront, a row house is painted in rainbow colors—yellow, pink, blue, purple and red. The exterior needs a powerwash. Another row house is boarded up.

People didn’t always know how the graffiti got there, only that it was there saying something. On a wall or on some space, there were those big unreadable letters and bad illustrations that made the city look bad. I would hear tales of work accomplished, and what was done to throw a work up overnight, the tools–the airbrushes, paintbrushes, and nozzles.

Bomb the semiotosphere

By controlling the atomizer, the thing that makes paint into microscopic droplets, the street artists were fighting the atomization of modern man. It was a rebellion against the psychic colony—f–k your copy! It’s what EKG touches on his “Technologies of Human Nature,” a wall-sized hierarchical chart created on black paper with orange oil sticks. He attempts to summarize street art’s ideological foundation, when he writes “bomb the semiotosphere!”

But what I remember most about street art is the interpersonal exchange–what was drawn into sketchbooks and shared, what a man or women in dire straits decided to do with their creative impulse, and who they decided to share it with. Too often in oppressed and forgotten areas of America’s inner cities, people don’t get a chance to unguardedly show that they value their own folk. The creation of art for the purpose of expression and engagement with other beings, creative or not, allows for this. In the places where graffiti was birthed and nurtured, this creative force can oppose the nihilistic impulse. This is the magic of hip-hop at its core, and street art is a part of that. Unfortunately, in America there’s no shortage of circumstances that beckon our most volatile selves. A work of art can only do so much.