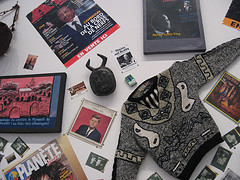

Detail of room installation, Abraham–Friend of God, by Georges Adeagbo

A bold acquisition of contemporary art with a global pedigree–Georges Adeagbo’s Abraham—L’ami de Dieu (Abraham—Friend of God), Philadelphia version–is now up at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It is part of Out of Words, the second in the Notations series of contemporary art exhibits, curated by Carlos Basualdo.

This exhibit embraces textual art, including works from Glenn Ligon, Bruce Nauman, On Kawara and Joseph Kosuth, as well as from Adeagbo.

This carving, based on the 13th c. tomb relief Recumbent Knight in the museum’s collection; Benin artist Hugues Hountandji carved it specifically for this installation, based on an image in a PMA collection catalog.

But it’s the Adeagbo that holds the largest piece of real estate in the exhibit and that challenges the most. It’s also the first time the Philadelphia version of the piece has shown–it was made specifically for this time and space.

Local artifacts mix with others from around the world.

The piece is a room-sized installation of clips from an international and local blend of magazines and newspapers, paintings, carvings, umbrellas, no parking signs–all sorts of things–tacked on the four walls around two floor displays on oriental rugs. The floor displays look like a cross between street vendor’s displays and ad hoc altars of books and images and record covers, plus a small carving at the top of each. One even has a wine bottle.

An altar-like and vendor-like display of books, records and more on a rug, part of Adeagbo’s Abraham–Friend of God installation.

As I went around the exhibit, I was struck by how the texts and pictures and objects, with their international sources, added up to a sense of one world, one mythological backbone that’s meaningful across borders. It’s a retelling of all the stories in the world–and especially the American story–from the point of view of one man from Africa. The story of Abraham and Isaac becomes the myth exemplifying other facts of our world, including American slavery, the death of John F. Kennedy, the death of Martin Luther King.

Adeagbo included a number of local items, such as clippings from the Philadelphia Inquirer, in his installation; his material is expansive and quirky enough to include this Banana Republic shopping bag.

The articles on the wall engaged me for quite a while as I walked around the room, and that act of walking and reading and looking became a paradigm for the motion of ideas and goods and also a paradigm for the motion of human migrations–a narrative at once sweeping and particular.

Sometimes the particular juxtapostions made sense to me, sometimes not. Sometimes I didn’t bother to figure out why they were there; sometimes just a glance gave enough information–like the sweater pattern reflecting something of the carved mask nearby.

A modern sweater and a traditional mask reflect one another’s patterning impulses.

The overall effect, here, is a mix of grace and obsession working to make sense of an overwhelming amount of information. And because our worlds are so thoroughly connected into one global organism, the need to make sense of the amount of the ever-growing mountain of information is ever greater.

Adeagbo is more a collector and organizer, not a maker of things. The carvings and the paintings were by other Benin artists–Esprit (Eli Adanhoume) made the paintings, Hugues Hountandji and Eduard Kinigbe made the wood carvings, and Boniface did the lettering on glass.

Abraham is in its second incarnation here, the first having been at P.S.1 in New York in 2000/2001.

At the other extreme of verbosity hang the other pieces in the show. Most long-winded is Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (I’m turning into a specter before your very eyes and I’m going to haunt you,) in which a quote from The Blacks, by Jean Genet, finally gets obliterated by blackness, a concrete representation of the words–and a discussion of the artist’s identity between two opposing sides. This piece and the On Kawara Date Paintings belong to the PMA.

Glenn Ligon’s Untitled (I’m turning into a specter before your very eyes and I’m going to haunt you), oil and gesso on canvas

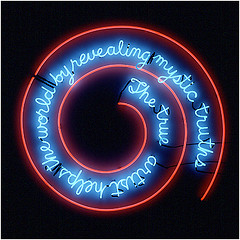

Like Ligon’s piece, Bruce Nauman’s spiraling neon piece, The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths, is also about identity spelled out from multiple points of view. Nauman is selling himself a bill of goods, and he’s selling us all a bill of goods, hanging his sign in the church of art. Both these pieces are great, and prickly. And both these pieces are more closely aligned to some of the issues in Adeagbo’s.

Bruce Nauman’s neon piece.

But there’s a generosity of spirit in Adeagbo, a looking outward, that puts to shame the self-absorption implied by both these pieces–especially the Nauman.

The neon in Kosuth’s Three adjectives (red, yellow, blue) gives this piece some sizzle beyond its obvious content–the spelling out of the words red, yellow and blue in red yellow and blue neon. But the identity of the artist is submerged, the affect cool and impersonal. And the On Kawara reductive dates are in so many ways about absence that they become the polar opposite of Adeagbo’s big embrace of everything.

This second Notations exhibit is also the second to include a recent international purchase by Basualdo, the previous one including Thomas Hirschhorn’s injured globes. (You can also read Roberta’s interview with Carlos Basualdo and see our flickr sets of Notations: Energy Yes!here and here.