Thomas Eakins, The Agnew Clinic, 1889.

If you’re all frothed up about the Thomas Eakins Gross Clinic debacle (and who isn’t?) I want to recommend you go hear Pulitzer prize-winning historian William S. McFeely speak about his new book on Thomas Eakins, “Portrait: A Life of Thomas Eakins” at the Free Library this Thursday night, Dec. 7 at 7 p.m. It’s a free lecture–no tickets required but you might want to get there early to get a seat.

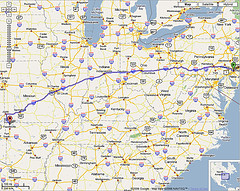

The road from Philadelphia to Bentonville, Arkansas, proposed new home for Eakins’ The Gross Clinic.

I read an advanced copy of Portrait a few months back and while it’s not written as gracefully or powerfully as Sidney D. Kirkpatrick‘s The Revenge of Thomas Eakins, which set the artist in the context of the city and all the political, economic and social mores at play (see my review of that book) Portrait goes farther than Kirkpatrick in judging the painter’s sexual identity. McFeely assesses some facts, makes a leap of imagination, and calls Eakins a homosexual. I’m not sure his leap of imagination works because I don’t think there’s new evidence offered. But the desire to out the artist once and for all is going to separate McFeely’s book from the pack.

Here’s McFeely on P. 49, right near the beginning of the book:

Homosexuality. That word, despite our somewhat self-righteous liberality, still sprinkles itching powder over any discussion of Eakins. Having sexual relations with men, as Eakins may well have, led triumphant champions in the gay world to claim Eakins as a brother. Traditionalists hold that Eakins either wasn’t gay or never succumbed to temptation–or that it doesn’t matter. But it does matter; sexuality is, of course, part of the whole human, an essential part. To ignore that dimension of Eakins’ life would be to have only a partial person in view. To view it as the single important factor in his life does the same disservice.

The author goes on to argue that when Eakins was in Paris, “it is likely” that some or most of his art student friends were homosexual, and he mentions as suspicious the artist’s break-up with Emily Sartain who wrote to Eakins after seeing him in Paris that he was “ill, bodily and mentally.” The author acknowledges that this and the other things he cites are not really evidence, but quotes Graham Robb‘s book Strangers, a study on 19th Century homosexuality saying that “the lack of evidence is the evidence.” And that’s enough for him.

Thomas Eakins, Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, 1871

Like I say, this is what the book is going to be called out or noted for — the forthright assertion that the artist was gay. The assertion that lack of evidence is the evidence strikes me as pretty weak. And I’m with those who say it matters less than the larger portrait of the man, his art and his treatment by the world.

Apart from that, the book is a good biography that contextualizes the artist well. Feely deals nicely with Eakins’ transcendentalism (P. 48). He calls him a 19th Century seeker like Thoreau, Emerson and Whitman. (P. 68) These statements/judgments ring true about the artist who almost became a physician and studied anatomy — as we all know — at Thomas Jefferson College of Medicine at the same time that he was enrolled at Pennsylvania Academy.

McFeely also talks about the artist’s six years of illness at the end of his life and sides with the speculation that it was lead poisoning from working with lead white over the course of his career that caused the illness. (P. 199)

All in all, Portrait is a good Eakins biography. And yet I’d pair it with the Kirkpatrick book for a truer picture. This is an artist who I think it’s safe to say is the best artist Philadelphia has produced. He’s worthy of two biographies in one year. In fact, he’s worthy of so much more.

Portrait: A Life of Thomas Eakins

by William S. McFeely

hardcover. ISBN 10: 0-393-05065-3 ISBN 13: 978-0-393-05065-3

320 pages

W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., New York