Francis di Fronzo, Stay, Part 3, oil on panel; in this one the ocean and the sky merge, an expression of limitlessness and unity that verges on religion.

I couldn’t help but think about the differences between traditional Japanese landscapes, which can be huge and panoramic (think a multi-paneled screen of the sort included in the Taiga and Gyokuran exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art right now–Andrea’s post here), and American landscapes and the German landscapes of Anselm Kiefer and Gerhart Richter. The attitude is 180 degrees different. Taiga’s views are neither threatening nor bombastic nor overwhelming. They are places for humans.

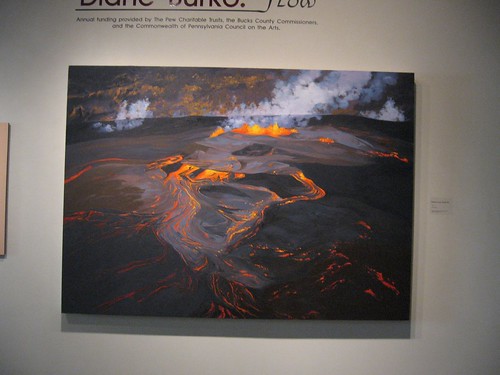

American landscapes are awe-inspiring descendants of Transcendentalism. They overwhelm with shock and awe, as in how mighty is the earth upon which we dwell. Look at a landscape of Diane Burko or Joy Garnett, but do not enter it. Shiver rather than walk into an April Gornik. (Oh, sure you can walk into an Avery, but he was looking at Asia, I do believe). As for Anselm Kiefer, his horizonless land is also overwhelming, and unwelcoming. And Gerhard Richter makes his aerial views dangerous places.

Diane Burko, Halema’uma’u Crater #3, 2000, oil on canvas

The landscapes and seascapes of Francis di Fronzo at Rosenfeld Gallery are none of these, and yet I couldn’t take my eyes of them. The PAFA MFA and Pew Fellow (2004) absorbed all that academy technique and puts it to a use that is hard for me to define. The paintings, many of them quite long, seem quite personal, quite real and unreal all at once. Sea merges almost imperceptibly into sky. Fields of wheat or grass go on and on, one blade at a time. Ocean foam up close looks 3-D and bubbling.

Francis di Fronzo, I thought You’d Be Here Too, Part 2, oil on panel

di Fronzo is walking a line between what is real and what we imagine is real. The paintings are intimate and sometimes filled with longing. They are empty of people, yet talk about people’s absence.

The work is quite beautiful, having the aura of nothing new here are the same time that they seem radical–questioning what it is that matters, what it is that landscape can convey. It’s a vision of great distance, great numbers, great repetition, over and over. The images are not enormously large. They can fit in a living room. But their vision is large and limitless. The oceans remind me of Vija Celmins drawings, which suggest the waves go on limitlessly. Of all the artists I mentioned above, it’s Anselm Kiefer’s muddy landscapes without end that di Fronzo’s grass lands bring to mind. di Fronzo is painting a visual expression of Walt Whitman’s multitudes in Leaves of Grass.

Also at Rosenfeld are encaustic works by Alan Soffer. Soffer will give an artist’s talk Sunday, May 20, 3pm at the gallery.

For another recent rumination on landscapes, go here.