Post by Andrea Kirsh

Verner Panton, 1970/2000, Phantasy Landscape Visiona II, (View 2), Wood, foam rubber and woolen fabric , 314 15/16 x 236 1/4 x 94 1/2in. (800 x 600 x 240cm), Vitra Design Museum, © Panton Design, Basel

I love New York City on a summer weekend when everyone who can has left for the beach or the country; it’s calmer than at other times. I headed for the Whitney where I approached “Summer of Love; Celebrating Art of the Psychedelic Era” with curiosity but also trepidation; after all, seeing one’s adolescence recast as history is sobering. The exhibition was busy for a weekday afternoon, largely with people much too young to have played the music on LPs, grown up with the posters or read the alternative magazines that the exhibition provided in abundance. My favorite overheard conversation was from a couple who were there with their seven or eight-year-old granddaughter. On reading a poster which featured a list of events from the sixties, the man nostalgically repeated “I remember this, I remember this…” The little girl finally said “I’m bored.”

Bill Ham, late 1960s, Liquid Light Show, Matte photographic color print , 11 11/16 x 153 9/16 in., Collection of the artist, © Bill Ham

The curators situated the art within concurrent social and political contexts but mostly ignored the art historical one. From my retrospective view, I realize that a lot of the material was hardly new. Light experiments have a long lineage, and this is the only area where the exhibition provided context, in the form of Thomas Wilfred’s last work, “Luccata (Opus 162)” (1967_68). The label helpfully mentioned that Wilfred’s “Lumia Suite” (1963_64) was on continuous view at MoMA from 1964 through 1980. I remember it in the basement, on the way to the auditorium, where a generation of museum-goers would have seen it. It had a major influence on all the later artists who worked in light (most particularly Earl Ryback, who worked on some of Wilfred’s pieces after his death, to keep them operational; the label didn’t mention this). Wilfred began working with his Clavilux, or color organ, which created moving forms with light, in the 1920s (in a realization of Kandinsky’s association of visual abstraction with sounds in “Klange,” of 1912). An even earlier exploration, in the 1890s, was Loie Fuller’s use of lights to create abstract patterns when projected onto her swirling drapery; Fuller captivated and was depicted by a generation of artists, most notably Toulouse-Lautrec.

Peter Sedgley, 1968, Video Disque 2: YOR, Screenprint on spun aluminum disc , Diameter 29 5/16 in., Collection of the artist; courtesy Austin Desmond Fine Art, London, © Peter Sedgley

Other pieces that recalled earlier art were Peter Sedgley’s “Video Disques,” (1968) _ essentially Marcel Duchamp’s Roto_Reliefs (1920) in day-glo colors, and the many solarized photographs used in sixties posters, an effect that dates at least to the late 1920s-30s work of Man Ray and a number of other experimental photographers; the posters’ fluid forms have obvious sources in Art Nouveau, and I couldn’t help but see the music and light shows of venues such as the Filmore and Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable Show as the realization of Wagner’s “gesamkunstwerk.”

Marcel Duchamp, Rotorelief, The Rotoreliefs first appeared in the film Anemic Cinema where they alternate with discs bearing inscriptions. The discs were meant to be placed on a record-player according to the following instructions: “The disc should turn at an approximate speed of 331/ 3 revolutions per minute, this will give an impression of depth, and the optical illusion will be more intense with one eye than with two!” M.D.

Even the mind_altering drugs, which may have looked new to middle-class Americans in the wake of the 1950s (their ubiquity among the young probably was new) have a history in literature dating to 1822, with Thomas de Quincy’s “Confessions of an Opium-Eater.”

Yayoi Kusama, 1996, Infinity Mirrored Room. Love Forever, Stainless steel, mirror, and light bulbs , 78 � x 42 1/8 x 40 1/8 in., Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery,© Yayoi Kusama

A feature of the social landscape that the text didn’t mention but the work made clear was the primarily decorative place of women (then called “girls”). The only art by women were Linda Benglis’ psychedelic red-carpet of a floor piece, Yayoi Kusama’s Mirrored Room, three gouaches by Adrian Piper (juvenilia, and certainly not recognizably hers) and Marian Zazeela’s collaboration with Lamonte Young, as well as photographs of a few musicians, notably Janis Joplin. Yet the naked female body was much in evidence in photographs, videos, posters and artwork.

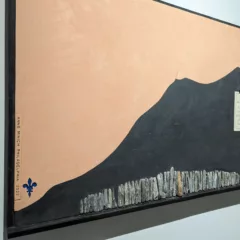

Verner Panton, 1970/2000, Phantasy Landscape Visiona II, (View 1), Wood, foam rubber and woolen fabric , 314 15/16 x 236 1/4 x 94 1/2in. (800 x 600 x 240cm), Vitra Design Museum, © Panton Design, Basel

The prevalence of drugs during the sixties meant that taken straight, some of the work was pretty thin on ideas and of limited visual impact to the unaltered eye. I thought this was the case with Gustav Metzger’s “Liquid Crystal Environment” (1965), although Vernon Panton’s beautifully_crafted “Phantasy Landscape Visonia II” (1970/2000) held up very well and was of particular delight to the visitors with young children. Panton is surely behind the entire design of Stephen Starr’s restaurant, Pod, which includes chairs he designed.

If you missed the 60s or want to re-live a bit of them, “Summer of Love” is a good place to start.

Video in Various Forms

I caught an extraordinary exhibition at the Asia Society: “Condensation: Five Video Works by Chen Chieh-jen” (up through August 5). Chen is a Taiwanese photographer who turned to video in 2002, and the exhibition consisted of four single-channel pieces and one three-screen projection. Chen’s work is about history as story-telling, who tells it and how it is received. He is concerned about workers displaced by globalization, particularly the Taiwanese who were long isolated from contact with the rest of the world. It is entirely anti-spectacular. Chen restricts his palette (some of the work is black and white and the color work is restrained), only uses sound in one work, and very little there, and the tempo of his movements, as slow as Butoh, imparts a gravity to the subjects.

History, it is said, is written by the victors. In “The Route” (2006) Chen attempts to re-play Taiwanese labor history as he wished it had occurred. In 1997, during a dockworker’s strike in Liverpool, American, Canadian and Japanese dockworkers supported their colleagues and refused to unload a ship that had been loaded by scabs. Unaware of the strike, the Taiwanese dockworkers unloaded the ship despite their own labor problems. In 2006 Chen worked surreptitiously with a group of the dockworkers to depict their solidarity with international labor via a strike enacted for film.

“Lingchi – Echoes of a Historical Photograph” (2002) is based a picture of a lingchi (“death of a thousand cuts”) execution in 1904 or 05; the photograph became a postcard (as did photographs of lynchings in the U.S.) which supported European prejudices about China and was discussed in French historical and philosophical writing. The three-channel piece shifts from the perspective of the victim to that of the observant crowd, and moves among the time of the event, time recalled by the participants and later time, when the photographs substitute for the event. It raises questions about death as spectacle, the responsibility of photography, and our consumption of images of torture and death. Chen’s is remarkable political art that does not tell you what to think and allows his subjects their complexity.

There was more self-conscious story-telling in the session I caught of “Scanners,” the 2007 New York Video Festival at Lincoln Center. The program was organized by Berta Sichel of the Reina Sofia, and featured a group of Europeans: Marine Hugonnier (one of the three films by the French artist which were screened at the PMA from April through late July–see post), as well as work by Erik Schmidt and Julian Rosefeldt (both German), Arthur Kleinjan (a Dutchman who was present for the screening) and the Spaniard, Dora Garcia. Several involved confrontation with distant cultures (Brazil, India, Egypt), and all of them played with the audiences’ expectations about film genres. They were all narrative, but none had a simple resolution. Schmidt made clever (and occasionally funny) use of sound to accompany a story with no dialogue. Rosefeldt made humorous comparison of the outsider’s view of India with India’s self-presentation in Bollywood films, and Kleinjan combined an unresolved mystery with his narrator’s meditations on the un-knowability of a foreign culture. Garcia presented a dialogue then a scene enacted to the text, with the implication that an entirely different story might be made to fit the dialogue. These videos were longer than the typical U.S. entries in the festival, due to the ample government funding for artists in Europe, no doubt. Next year the Film Society of Lincoln Center will be showing new video work throughout the year instead of grouping it in a festival format.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.