Post by Andrea Kirsh

Nalini Malani, Talking About Akka, (detail), 2007, Tryptich, 183 cm x

100 cm each, overall size 185 X 300 cm, Acrylic and enamel reverse

painting on acrylic sheet, Courtesy of the artist

The Irish Museum of Modern Art has several interesting exhibitions at the moment and I went to see two of them: surveys of Nalini Malani and Lucian Freud. Access to IMMA’s primary galleries is via a glass staircase which opens onto what is usually a light-filled landing; but for now all that is changed and one enters a different world, a darkened space with red walls.

Women’s stories by Nalini Malani

The Indian artist Nalini Malani, in her first solo exhibition in Europe, has installed a large, five-screen video installation beside the landing: “Mother India; Transactions in the Construction of Pain”(2005). Malani calls the piece, composed of historical and contemporary photographs, filmed imagery and computer animations, a “play.” It is the artist’s own story: born in Karachi in 1946, she and her family escaped to India the following year when Pakistan was partitioned. Educated in Bombay and Paris, Malani is both an exile and a citizen of the world; her work draws upon her serious study of both local and international traditions, stories and imagery. (For a 2004 artblog post on Malani in Chelsea, go here).

Nalini Malani, Sita/Medea, 2006, 183 X 122 cm, Acrylic and enamel

reverse painting on acrylic sheet, Courtesy of the artist.

“Mother India” is compelling, intense, visually lush and ultimately dispairing. The subject it addresses is old and likely to remain with us. It begins with a quote questioning the fact that the project of nationalization is “inscribed on the bodies of women,” and ends with a citation from the social scientist, Veena Das, about the association of nationalism and pain. Its paradigmatic image is the face of a young girl and the question of her, and hence, India’s future. We see images central to the fashioning of the independent state: the spinning-wheel, the cow holy to Hinduism, Ghandi on his bier; these are layered with images from the streets, including popular posters and signs for Coca Cola. The piece is punctuated with a woman’s face staring at us, and another full-screen image of her open mouth, perhaps screaming.

Nalini Malani, Remembering Mad Meg, 2007, 1500 by 500 cm (adaptable),

Two channel shadow/video Play. 2 DVD’s not in sync, Eight rotating Lexan

cylinders with metal framework and motors, Installation view Irish

Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Photo (c) Denis Mortell

The second installation, “Remembering Mad Meg”(2007) takes its title from a painting by Pieter Brueghel and includes visual references to Goya, to traditional Indian narratives and anatomical texts; but the combination of visual imagination and apocalyptic imagery also recalls the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. The installation consists of eight large Mylar cylinders hung from the ceiling and slowly rotating; figures painted on the Mylar cast changing shadows on the wall as lights and images are projected through them. It is like an expanded version of one of those nineteenth-century shadow devices that entertained people before film or television. Malani is particularly interested in stories around strong female figures and goddesses; in this respect her work recalls Nancy Spero’s project of reviving female archetypes. The animation of the images and their overlapping appearances and disappearances suggests figures seen in a performance, hallucination, or a dream.

Malani used a quote from R.B.Kitaj once, in lieu of an artist’s statement and like Kitaj she creates an art of non-linear narrative using historical and allegorical tales, those master narratives by which we define ourselves. Her large paintings involve layered imagery from traditional and popular culture, myth and literature as well as patterning, which brings to mind Sigmar Polke’s overlapping images; but her work does not resemble anyone else’s. Her technique involves reverse painting on Mylar, like the reverse-painting on glass used in European vernacular painting (and adopted by Kandinsky and other artists interested in folk sources). Malani has created an art that is as visually rich, intellectually varied and as politically charged as the world she has known.

Re-viewing Lucian Freud

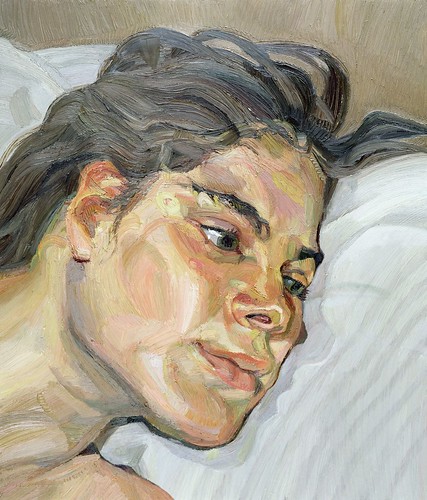

Lucian Freud, After Chardin (Large), 1999, oil on canvas, 52.7 x

61 cm, Private Collection, Photo: Courtesy Acquavella Contemporary Art,

Inc., (c) the Artist

Twenty years ago I saw a retrospective of Lucian Freud’s work at the Hirshhorn, so I approached the exhibition which Catherine Lampert organized for IMMA wondering what I would learn; the exhibition is in Dublin through Sept. 2, then travels to Louisiana Museum of Modern Art and the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. I knew that Freud’s paint-handling would be rewarding; for anyone who loves paint, this is a virtuosic performance by a great master. The exhibition of 50 paintings and 20 works on paper (mostly etchings) turned out to be especially revealing of the artist’s working process, for two reasons: firstly, the works were hung very low (I’d say 8 to 10 inches lower than museum standard), which created an intimate scale and gave the visitor the same view-from-above that the artist often employs; and secondly, the exhibition includes a number of photographs by Bruce Bernard of Freud’s studio, often with unfinished paintings on the easel. These were hung close to the finished paintings, giving a chance to see how they had developed.

Freud’s palette is as restricted and distinctive as Rembrandt’s; I could recognize one across a gallery, even out of the corner of my eye. His mature work makes a remarkable association of paint and flesh, and he has a rare appreciation for the qualities of skin. In “Portrait on a White Cover” (2002-3) Freud depicts the translucency of the model’s flesh which reveals a vein along her leg; this made me think of the same effect, which I’ve always loved, in Rubens’ “Chapeau de Paille” (National Gallery, London), where the artist indicates the veins in his sister-in-law’s decolletage.

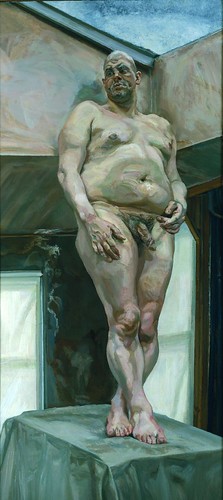

Lucian Freud, Leigh under the Skylight, 1994, oil on canvas, 297.2 x

120.7 cm, Private Collection, (c) the Artist

But his paint-work has changed considerably over the years, and during the past two decades has come more and more to employ a distinctive effect I will call the emphatic impasto: highly-textured paint (usually achieved through brushwork, at other times because of additions to the paint itself, probably pallete-scrapings) which concentrates on the focal points, just where a traditional painter might employ more detail. In the first room there’s a larger than life-size painting of the larger than life-size Leigh Bowery, “Leigh Under the Skylight” (1994). The rough paintwork is concentrated on Bowery’s hands and groin at the picture’s center, then, moving upward, on the flesh below his belly-button, his fleshy breasts, stubbly chin and the pate of his shaved head. At times I thought this use of impasto created problems, such as in the portrait of “The Pierce Family” (1998), where facial features became lost and the baby ends up with large, black smudges on his forehead.

The exhibition begins with some of Freud’s very earliest work from 1940, and charts the remarkable career of an artist who has extended the currency of figurative painting. I began to think about what distinguishes his work from earlier portraits or nudes, etc. Certainly the emotional tenor of his work is consistent with post-WWII existentialist writings and the art they influenced. The formal challenges Freud sets himself are unthinkable earlier, as are his adjustments to optical veracity: the square formats (the hardest to compose), the intentionally-awkward poses, the beds that seem ready to slide off the floor (much as Cezanne’s tables seem to lack right angles) and facial features that have shifted slightly. Freud’s work also lacks any traditional decorum: the Bowery painting focuses on his groin, the nude women splay their legs wide, and the artist paints from a viewpoint looming above his models. And then there are the fragments, some of my favorite paintings; work not interrupted, but intentionally incomplete. The fragments reveal Freud’s highly-unusual method of bringing part of a figure to completion when the adjacent part is not even blocked-out, or interrupting a form, such as a bit of the right jaw in “Girl’s Head, fragment” 1973-74. Appreciation of the fragmentary began with Rodin, and Cezanne exploited questions around finish, but Lucian Freud has extended their investigations and challenges us to re-think our ideas about painting and representation, and their possibilities today.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.