Alexander Calder Necklace (1930), brass wire, ceramic and cord loop, 15 3/4 in., photo © Maria Robledo, courtesy of Calder Foundation, N.Y. Calder made this for his mother as a 64th birthday present and wrote her that he’d found the fragments of ancient pottery along the parapets of the citadel in Calvi, Corsica.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) is filled with wonderful and entertaining exhibitions at the moment, and what’s more they are shows that will appeal to family and friends who may be wary of art. They’re all thoroughly respectable academically as well as funny – and I feel strongly that humor is to be taken seriously and valued in art. The Perelman Building is a treasure house; the most prominent exhibition there being Calder Jewelry (through Nov. 2, 2008).

Alexander Calder’s jewelry is an endless testimony to the imagination. He didn’t make jewelry in any conventional sense – he made body art, with the emphasis on art. Some pieces could easily be worn, others were certainly more conceptual. Calder occasionally used gold, more often silver or copper wire and the only baubles he set in them were bits of broken glass bottles and mirrors, pebbles or the shards of broken ceramics. His technique is all on view – a sort of home-made, folks-y handling, equivalent to Hemingway’s stripped-down prose, that becomes drawing with wire and belies his superb technical skill. When he sets one of those shards or pieces of glass he wraps wire around it and tethers it to the body of the necklace or pin with every twist of the attachment on display; the hammer-marks, grommets and fasteners are always visible. Despite his overt modesty he was truly an alchemist, turning dross into gold!

Alexander Calder Earrings (c. 1949), silver wire, 4 x 4 in. each, Calder Foundation, N. Y. and Display Head for Jewelry (1940), sheet metal, wood and paint, 13 x 7 x 4 in., collection Miani Johnson, N.Y., photo © Maria Robledo

Some of my favorites: a wickedly funny neck-piece titled The Jealous Husband (c. 1940) which uses beaten brass wire to create swirls across the wearer’s bosom and has sharp, protective claws protruding from both shoulders (or are those cuckold’s horns?); a thoroughly useless pair of steel wire spectacles (1932) that bear a strong resemblance to a Saul Steinberg drawing; a Chainmail necklace (c. 1940) formed from hoops of fine silver wire that calls attention to the chest rather than protecting it; and a Crown of Leaves (c. 1940) made of brass wire that is as far from a formal tiara as possible – looking instead like a party costume for Daphne in the process of becoming a tree.

The work is inspiring and joyful but I have problems with the exhibition. The first is the concept; Twentieth-century artists fought hard to break down hierarchies of the arts, and major artists including Calder exhibited small, useful objects, ceramics, furniture, clothing etc. along with their paintings and sculpture. In one of his earliest exhibitions, in 1929, Calder included paintings, wood sculpture, toys, wire sculpture, jewelry and textiles, and listed them all in the exhibition title. I’m sure he never said to himself today I’m a jeweler, tomorrow I’ll be a sculptor. These distinctions reflect the bureaucracy of the museum and the exigencies of the auction house imposing themselves on the artwork. Besides, the jewelry is much more interesting within the continuum of Calder’s endless playfulness and unconventional sensitivity to materials, his formal concerns, technical skills and anti-authoritarian stance. The Whitney Museum happily exhibits Calder’s Circus – a group of toy-sized models made of wire that Calder manipulated for performances, without worrying about categories. The last time I saw a significant group of Calder’s jewelry was at the Cooper-Hewitt in 1989, The Intimate World of Alexander Calder, a marvelous exhibition which included toys, useful household and cooking objects and hardware, such as a toilet-paper holder, that Calder made for family and friends.

Alexander Calder, on wall: Necklace, (c. 1943), silver wire, loop 34 in, pendant 5 1/4 x 3 3/4 in.; on surface: Bracelet (c.1947), gold wire, 2 3/16 x 2 7/8 x 2 9/16 in., Cufflinks (c. 1940), silver wire, 1 ½ x ½ x 3/4 in. each, Tiara (c. 1938), silver wire, 4 ½ x 7 x 6 1/8 in. all Calder Foundation, N.Y., photo © Maria Robledo

Not only does the current exhibition strip the work of its context within Calder’s oeuvre, it rarely hints at its art historical context other than the fact that some pieces were gifts to family and fellow artists, nor does it acknowledge Calder’s serious study of other body adornment; the label for one fish pin doesn’t mention that the motif comes from Max Ernst and labels for a number of necklaces make no mention of their references to African, Celtic or pre-Colombian jewelry, although the absolutely stunning catalog does fill in those blanks. The exhibition opens with a touching group of the endless gifts he made for his wife (whose unlabeled photograph hangs nearby), but the only other bit of context on view, large photographs of several of the pieces being worn, isn’t labeled at all; I may recognize Peggy Guggenheim (who commissioned his jewelry) and Brooke Shields (who certainly didn’t; I suspect it’s a fashion shot), but other visitors may not know who they are. But my major complaint is with the staid display, which I understand was dictated by the Calder Foundation, and indicates a discomfort with the fact that this work is fun and sometimes funny. The tasteful, generic installation could have been intended for Pre-Colombian Gold or Chinese ceramics.

But go, laugh and enjoy yourself! This is significant and inspiring work by one of the great figures of Twentieth-century American art, and laughter is allowed.

Further Gems Upstairs: Archive Acquisitions in the Library

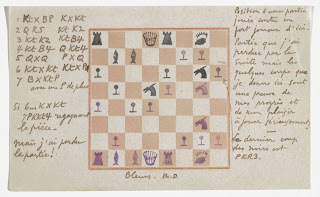

Marcel Duchamp, Chess scorecard made with stamps designed by the artist

(1919), Arensberg Archives, gift of the Francis Bacon Foundation, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. One of several pieces of Duchamp’s from the PMA’s archive on current view in the Perelman Building library.

If you haven’t been to the beautiful, new library now is the time, for two display cases are filled with gifts to the museum’s archives that indicate just how rich and diverse that collection is. There’s Benjamin Franklin’s edition of Cicero’s essay on old age (an astute interest in the field prior to the greying of the baby boomers), an early American book on carpentry techniques that uses pop-up illustrations and my favorite, Marcel Duchamp’s passport, with official photos looking much like portraits of Duchamp by fellow artists.

Fashions of Fancy: Kansai Yamamoto

Also upstairs is a tiny gem of an exhibition drawn from the PMA’s collections: Hello! Fashion; Kansai Yamamoto (1971-1973). It includes just nine of Yamamoto’s outfits (all gifts of Hess’s stores of Allentown, his first American outlet), six pieces by other Japanese designers (Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake), looking rather sedate in comparison, and two wonderful, short films. But that’s enough to change your idea of what clothing might be. The film of London and Tokyo fashion shows is full of outfits that might have been intended for a modern Gypsy Rose Lee for they come apart with a snap, revealing scantier outfits beneath; the other film records a literally spectacular event filled with effects of lighting, fireworks, smoke, rigging and a cast of thousands, a similar aesthetic to the recent opening of the Beijing Olympic games.

Kansai Yamamoto, Evening Cape, Top, and Pants (1971)synthetic satin, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Hess’s Department Store, Allentown.

Yamamoto creates costumes more than clothing in the conventional sense, and draws his inspiration from a broad range of traditional Japanese forms: Kabuki theater as depicted in woodblock prints, kites (see first image, above), samurai archer’s targets and tattoos. One pair of trousers has legs which look like flamenco dancers’ skirts: each is a full circle; an ensemble of shorts and a top is accompanied by leggings inspired by firefighters’ protective clothing and worn with a red hood (David Bowie was photographed in a similar outfit in 1971); a cape inspired by hippie macrame (above) consists of thick, floor-length coils of satin, knotted at the yoke and hanging freely from the shoulders, a perfect dance costume and fortunately shown in motion in one of the films. The exhibition is an eye-opener; why don’t I know this work? Many thanks to the PMA’s costume and textiles department!

The Afterlife of Ephemera

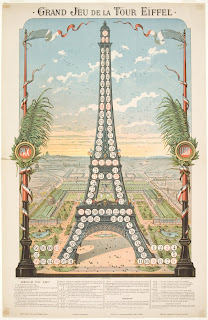

The Big Eiffel Tower Game, souvenir of the Paris World’s Fair of 1889, Allard et Laval, French, active c. 1889, published by Courmont Frères, Paris, France, 1889, chromolithograph, 30 1/16 x 19 1/2 inches, Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Alice Newton Osborn, 1961.

If you cross the street to the museum’s main building there’s yet another exhibition that rewards getting out of the heat: Curious and Commonplace; European Popular Prints of the 1800’s. Don’t worry about the lengthy title; the exhibition is filled with the sorts of printed materials that were originally too ordinary for anyone to save; one wonders how these examples, mostly printed in Metz and Epinal, survived. Prints were the means for circulating visual material before photography; the exhibition includes prints of sensational crimes (before tabloids), Napoleonic propaganda as well as an anti-Napoleonic illustration of his defeat at Waterloo, fashion plates, greeting cards, advertisements, caricatures and satirical prints, playing cards and all sorts of children’s toys and games including stage sets, jumping-jacks and board games which would have been pasted onto cardboard and cut out.

The Miraculous Distillery for Ridding Husbands of Their Bad Habits, Francois Georgin, French, 1801-1863, published by Pellerin, Épinal, France, 1839, stencil-colored relief print, 11 15/16 x 21 3/8 in., Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Alice Newton Osborn, 1958.

My favorites? Well, who can resist an illustration of The Miraculous Distillery for Ridding Husbands of their Bad Habits (late 1830s) – my husband has no bad habits, of course, but the contraption would certainly be useful for other relatives and neighbors. I also love the Big Eiffel Tower Game which, was a souvenir of the 1889 Paris World’s Fair and authorized by the tower’s architect. The tower itself was meant to be a temporary structure so this was ephemera about ephemera. Then there’s the New Goose Game: a board game shaped as a goose, whose origin can be traced to Francisco di Medici in the Sixteenth-century. Now that’s a provenance for a bit of fun!