Giant green strawberries float down in Pipilotti Rist video installation, Pour Your Body Out

If your idea of sex is gorgeous and transcendent, there’s a show at MoMA for you.

And if your idea of sex is prurient and the body’s animal qualities trouble you, there’s another show for you, also at MoMA.

And the top miracle of all–both these shows are by women, Swiss video artist Pipilotti Rist and South African artist Marlene Dumas. Pairing them in our heads, the two shows gave us plenty to enjoy and react to.

Pipilotti Rist

People lounging in the atrium in the Pipilotti Rist video installation, Pour Your Body Out.

The installation that comes in gorgeous, saturated colors is Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out, 7,354 cubic meters of intense, melting colors that transform the museum’s atrium space into the Love Boat. There’s even a white shag carpet with a gigantic circular sofa occupying the center of the room. Signs at the door suggest you start a conversation with someone while you’re in there. People obeyed–reviving Flower Power in this Winter of Love.

And what’s an orgasm without a little noise? The music has a groaning quality that reminds us of whale calls.

A giant face fills the wall in Pipilotti Rist’s video

The video’s scale creates a Brobdinagian world of flowers bigger than cars; bare toes as big as elephant feet, squishing in mud; piglets bigger than a Viking stove; and an enormous pink-fleshed naked woman tossing a bed-sheet-sized mane of strawberry hair.

The video has similar visual wizardry and similar she-comes-in-colors glow to her earlier video Wicked Game, which we saw at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in 1999/2000–a video that for both of us became a touchstone for what an art video can be.

Pipilotti Rist, Pour Your Body Out

The morphing images that evoke transcendent sensations brought to mind Swiss artists Fischli and Weiss, and their “Flower Projection” slide show of flowers and nature dissolving into each other. But Rist, by putting the human body in that natural world, and by pumping up the scale and using video (seven projectors worth), adds dimensions and heat.

A video of Rist talking about her video is on the MoMA site.

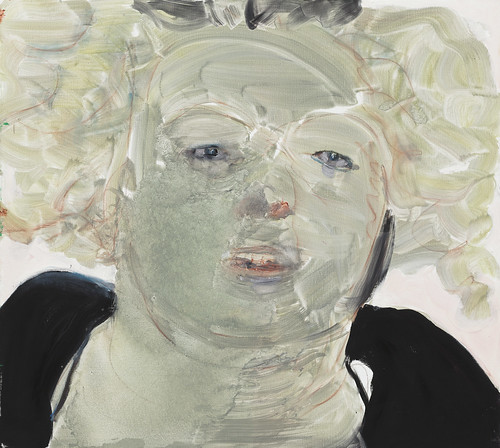

Marlene Dumas

Marlene Dumas

Dead Marilyn, 2008

Oil on canvas

15 3/4 x 19 11/16 in.

Private Collection, New York

© 2008 Marlene Dumas

If all was “luxe, calme and volupte” with an upbeat embrace of humanity and the natural world in Pipilotti Rist’s atrium, Marlene Dumas’s Measuring Your Own Grave — on MoMA’s 6th and 3rd floors– is the dead zone with “I see dead people” the recurrent theme. Dumas, the South African-born, Amsterdam-based artist, makes astonishing portraits, and this 30-year survey — with 70 paintings, 35 drawings and several large drawing series — catches the artist’s morbid eye, drawn again and again to images whose photographic sources belong in police archives.

Marlene Dumas

Death of the Author, 2003

Oil on canvas

15 3/4 x 19 11/16 in.

Collection Jolie van Leeuwen

© 2008 Marlene Dumas

Co-organized by MoMA and L.A.MOCA (where the show appeared last summer), Measuring Your Own Grave, gets its name from a 2003 painting by the same name. The show is organized around the artist’s portraiture, which is based mostly on Polaroids, personal snapshots and media images. Her practice takes the image far from its source, however, and into her deep psychological territory to mirror everyone’s fears of death, guilt, sex, and identity. The one self-portrait in the show, Self Portrait at Noon, commemorates the death of her mother in 2007. Dumas is especially fueled by the role of women in society and many of the images deal with woman as mother, as vessel for life, and as object of desire and sex worker. She’s not value-neutral about this and there’s simmering angst and anger throughout. Often her works deal with art historical references as she seems to critique the story of art as written in textbooks.

Marlene Dumas

Measuring Your Own Grave, 2003

Oil on canvas

55 1/8 x 55 1/8 in.

Private collection

© 2008 Marlene Dumas, photo by Andy Keate

The work is by turns hard to look at because of subject matter and hard to look at because — regardless of subject — the paint handling is brut and primal, with colors leaning to blood red, bruise purple and nauseating pthalo, all set in fields of grey, white and black. We thought of Warhol’s electric chair and car crash paintings when thinking about Dumas’ attraction to violent imagery. Warhol, like Dumas was seduced by the morbid. He was also a voyeur — and many of these works have a voyeuristic tinge to them, inviting you to see something you wouldn’t see in “polite company.” Weegee is another comparison — street and crime photographer drawn to images of victims and the dead. Of course there’s also Gerhard Richter’s Baader-Meinhof series, which has quite an affinity with Dumas in terms of its questioning of human actions in the context of politics.

When she’s not seeing dead people Dumas can be an astute portraitist. Her series Models (1994), 100 single female portrait heads, shows a delicate touch and an artist almost hyper-sensitive to the personalities that bleed through ordinary photographs. This series is presented in its own alcove in a ceiling to floor installation as if it’s almost separate from what’s around it. And in a way it feels different. For here Dumas seems to let go of her own ego and let the portrayed face surface as a real distinct character.

Marlene Dumas

Magnetic Fields (for Margaux Hemingway), 2008

Oil on canvas

11 13/16 x 15 3/4″ in.

Collection Thomas Koerfer, Zurich

© 2008 Marlene Dumas

We talked a lot about Elizabeth Peyton in the context of the show. Peyton’s fascination with humans is skin deep compared to Dumas’ Jung- and Freud-fueled readings. We love that Dumas’ and Peyton’s shows (at the New Museum) overlapped since the comparison is a natural — women artists working from photos whose focus is exclusively on portraiture.

Marlene Dumas

Self Portrait at Noon, 2008

Oil on canvas

35 7/16 x 39 3/8 in.

De Pont Museum of Contemporary Art, Tilburg, The Netherlands

© 2008 Marlene Dumas

We also want to bring up Zoe Strauss whose photographic stream includes portraits of people who’ve been shot or who are destroying themselves through drug use. Strauss’ eye is not morbid as much as questioning and empathetic. And she, like Dumas, is fixated on the role of women in the world, although her works show mostly women who are seemingly lost. While Dumas is empathetic with her subjects, the empathy gets lost sometimes under the anger at society, which is quite near the surface of most of her work.

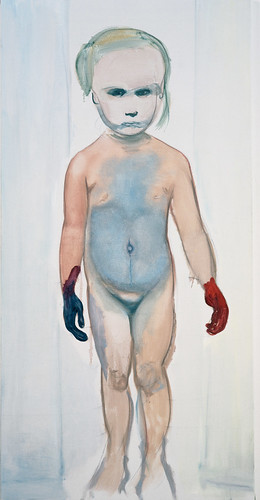

Marlene Dumas

The Painter, 1994

Oil on canvas

78 3/4 x 39 1/4 in.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Fractional and promised gift of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg

© 2008 Marlene Dumas

Critics are mixed on Dumas. Her subject matter is not easy, but then neither is Richter’s — and his embrace by the art world is unequivocal. We want to say that Dumas — as a woman focused on female bodies, minds and issues — is a harder sell (especially to male critics) because of that focus. Also — and this is true of this show — some of the work is strident. Sometimes she’s strident about politics (there’s a thinly-disguised Abu Ghraib piece that seems knee-jerk, and therefore slight), sometimes, about sex (there are several porno pix of women’s privates splayed on the canvas with the same mercilessness she gives to her dead folks). Dumas’ determination to see humanity at our most animal and our most hateful sometimes serves her well, sometimes not.

Marlene Dumas

The White Disease, 1985

Oil on canvas

49 3/16 x 41 5/16 in.

Private Collection

© 2008 Marlene Dumas

But Dumas is an outstanding portraitist and when she’s in the zone with the paint — as she is in many works here — the show sings. It’s a dirge of a song but very worthy of your time.

Marlene Dumas

Anonymous, 2005

Oil on canvas

27 9/16 x 19 11/16 in.

Garnatz Collection, Cologne

© 2008 Marlene Dumas