In an attempt to define his own reputation William Blake mounted an exhibition of his own work in 1809, above his brother’s shop in Soho. It was not a success.

Few people saw the sixteen watercolors and tempera paintings in the exhibition and the single review was scathing. Robert Hunt, writing in the Sept. 17, 1809 Examiner, wrote: … when the ebullations of a distempered brain are mistaken for the sallies of genius by those whose works have exhibited the soundest thinking in art, the malady [madness] has indeed attained a pernicious height, and it becomes a duty to endeavor to arrest its progress. Such is the case with the productions and admirers of WILLIAM BLAKE, an unfortunate lunatic, whose personal inoffensiveness secures him from confinement, and consequently, of whom no public notice would have been taken, if he was not … held up to public admiration by many esteemed amateurs and professors as a genius in some respect original and legitimate.

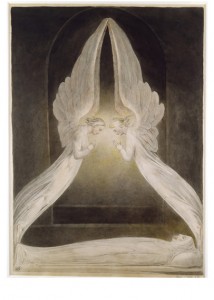

Tate Britain has recreated Blake’s exhibition, assembling the ten surviving paintings and indicating the missing works with blank areas on the walls (see photo above for the missing monumental painting), and reprinted Blake’s descriptive catalog with an introduction by the curator (Seen in My Visions: A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures edited by Martin Myrone). They have also most helpfully included a number of paintings by Turner and others, also exhibited in London in 1809, that met with more favorable response.

In Blake’s attempt to return to the glories of Renaissance and Baroque painting he formulated his own technique; what he described as “fresco” was in fact a glue-based tempera, many of which have suffered so greatly with age that it is hard to judge their original appearance. Fortunately the watercolors have survived well.

The exhibition reveals Blake as he wished to be seen and understood and is an early example of an artist going outside established art institutions in an attempt to control his work. It may be a heartening story for artists who feel out of step with current fashions and will likely cheer those who think the critics have gotten things wrong. It’s certainly a wonderful example of a museum making use of works in its permanent collection to bring about a greater understanding of their history.