Some great Pop artists who have fallen off the art historical map are now on view in the exhibit Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists 1958-1968, at the University of the Arts.

In resurrecting them, Curator Sid Sachs points a finger at the political realities of gender and power and the myth of good taste, and how they affect what we see, what we value, and what we choose to write into the record. Sachs’ portrait of the missing half of the story–the female half–expands the narrowed down narrative of Pop Art, which was simplified to the benefit of men, cutting out women and their conceptual–and sometimes aesthetic–differences.

A number of the 19 women in the exhibit disappeared because their devotion to career was subverted by the expectation that women belonged in the kitchen, not the gallery. Sometimes the women themselves let the careers slide. But mostly the social structure overwhelmed their ability to stay on course. That issue was exacerbated by the shabby treatment and lack of support they got from men who paraded as their friends and lovers. Galleries dissed them. Critics ignored them. Art schools belittled them after admitting only those women who were twice as good as men. The women were trivialized and marginalized, expected to be beauties rather than beautiful thinkers and talents. It’s the old story. And the end result was promising careers that foundered and petered out.

Some of the artists in this exhibit have achieved some level of recognition for their work–Vija Celmins, Yayoi Kusama, Niki de Saint Phalle, Faith Ringgold, Chryssa, Marisol and Martha Rosler. But none (except maybe Kusama) has the level of widespread recognition that Roy Lichtenstein or Ed Ruscha acquired. (Celmins’ recognition is not primarily for her Pop work). Yet each of these artists is arguably as important and profound, making art objects in dialectic with the culture of the time.

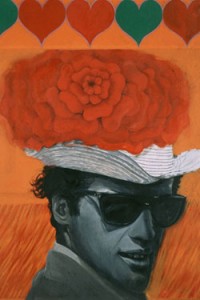

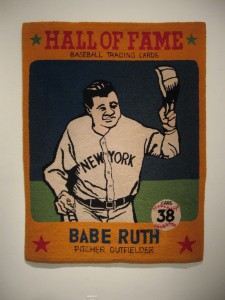

Pauline Boty’s portrait of French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo is enough of a reason to go to this exhibit. The painting is red-hot sexy and riveting, with a Freudian bed of roses, atop his head. Also tops is Dorothy Grebenak’s Hall of Fame hooked rug, filled with love not just for its subject, Babe Ruth, but also for all those grubby-handed young collectors of baseball cards. These are passionate works that bring their subjects into the artists’ own world–Belmondo in proximity to Boty’s booty and Ruth and the cultural phenomenon of baseball cards woven into family life.

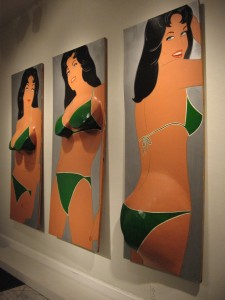

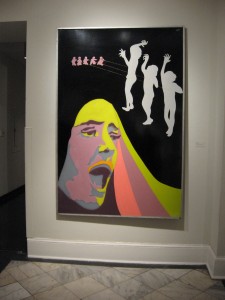

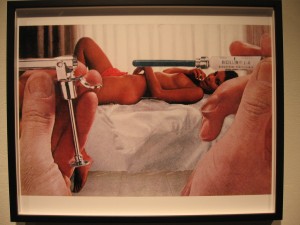

In Rosalyn Drexler’s news-based violent images, men become vectors of oppression and suppression–and dark fantasy. And in Idelle Weber’s Munchkins triptych, men lose their identity in another way, becoming robotic cogs in the wheels of society. Marjorie Strider gives comic-book flat images 3-D elements, for example pumping up a breast into a comic projectile in Green Triptych. Her witty painting Woman with Parted Lips carves an open mouth into a dry cave, hardly the ready, willing and able open mouth of comic books and True Romance.

Evelyne Axell captures the dreamy Peter Max exuberance and graphics of rock album covers in her portrait of Angela Davis and in her Kent State “Campus” painting layered on plexiglas and fiberboard–but with political content, well with content, period.

That’s part of what makes this show, a serious, art-historical correction, so great. It shows that these women were trivialized, but not trivial. Marisol seems like an obvious example, someone whose work was demeaned as slight and too likable/popular when in fact it is full of content. Sachs’ essay credits the ladies with inventing soft sculpture–a political act of taking art into the sphere of the body and homemaker skills. And they women explore the same slick,male-dominated world of advertising and popular media, inserting their own point of view on women as sexual beings–and it sure is different from how the men view it both in the popular media and in art. They use collage and bricolage, resin and print media, neon and plexiglas, needlework and felt-tipped pens.

Others in the exhibit are Chryssa, Kay Kurt, Mara McAfee, Barbro Ostlihn, Alina Szapocznikow (definitely an outlier with her Art Nouveau romantic style), Joyce Wieland and May Wilson.

There’s lots to see in this exhibit of 19 artists’ works, some of which took years to track down. The exhibit overflows from Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery into the neighboring Hamilton Hall and Borowsky galleries.

Here’s my Flickr set for more photos.