Those who care for modern art and particularly for art produced since World War II face challenges unknown from their experience with earlier artwork; not only materials known to be impermanent (newspaper, latex, chocolate) or of unknown permanence (plastics, color photographs, felt-tip pen inks) but also working parts, intentionally ephemeral work, and pieces involving hardware, such as cathode ray tubes, that become obsolete. Some works also include living material (animal and vegetable), current vernacular items, refuse and/or garbage. The presence of the artist, who inevitably retains a connection with the work, although not always one supported by moral rights law, also presents a profound change. Dead artists don’t talk back.

These questions were first raised in an international context in 1997 at the Amsterdam symposium, Modern Art, Who Cares? Organized by the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage (ICN ). Earlier this month 550 people attended a second symposium, Contemporary Art, Who Cares? organized by the ICN along with the Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (SBMK ) and the University of Amsterdam; attendees included conservators, collection managers, artists’ assistants, curators, museum directors, art historians and a good number of students. Some of us had also attended the ’97 symposium, but many represented the next generation which faces these questions at the beginning of their careers.

Joost Zwageman opened the event by discussing his recent novel, Duel, which very clearly presented the dilemma of traditionally-trained conservators now faced with the very different materials and ideas of contemporary work. The sessions that followed for 3 days addressed questions so different from those presented by traditional artworks that their caretakers have been forced to re-think the fundamental tenets of their practice.

Conservation is always an act of interpretation; should the initial physical form of a work be given priority (the usual Western standard) or should the history of use and possible damage be retained? The later is the choice in treating Zen tea bowls in Japan (discussed in my post of Jan. 13, 2009) and with many objects displayed in history museums. I heard a conservator at the US Holocaust Museum explain the damage [to the artifacts] is the story. The fundamental questions underlying most of the sessions were: 1) what constitutes the artwork? (an obvious problem with works that have functioning parts and equipment), 2) what defines authenticity? (is film transferred to video authentic?), and 3) who decides: artists and their estates, the current owner, art historians and philosophers, curators, the market?

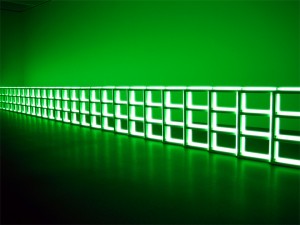

Reinhard Bek, head of conservation at the Museum Tinguely, Basel, described the conservation problem dealing with Naum Gabo’s Standing Wave at Tate. When still, the piece is nothing but a vertical rod on a base; the motor, which wears out, creates the motion that generates the form. The artist gave permission for a replica to be made as early as 1968, when it was too fragile to lend. Bek raised several points: the photographs of the original piece are part of its conservation, when artworks move from contemporary to historical their material authenticity becomes a priority, and the many stores of spare parts that fill museums (he showed an image that resembled a well-stocked hardware shop) are a stop-gap that will inevitably run out.

The conference continually raised provocative ideas. Conservator Christian Scheidemann suggested that the artist has full say during a work’s construction – and is always right – but once made, the art is in the conservator’s hands. But when is a work finished? There are no simple answers. Marianne Parsch, a conservator working in Munich, asked why we can’t accept the decay of artworks. There are dead bodies in all the storerooms, she declared. Contemporary art forces conservators into new roles as recounted by Susan Lake, director of collection management at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Ann Hamilton used local, Ohio snails in an installation and when the museum went to set up the piece they found out that the snails were considered invasive in D.C. The Hirshhorn was allowed a permit to use the same species only if Susan agreed to kill them once the installation was taken down. An audience member involved with archiving early video at the University of Dundee suggested that usage, to re-play (with time-based work) is a form of conservation.

The symposium broke into smaller working groups in the afternoons, and I attended one about working with artists in questions of preservation. Andreas Slominski was there with a curator and two conservators with whom he had worked. In discussing a work from 1991, one of a series of bicycles carrying multiple full plastic bags, leaning against a wall, Slominski made it clear that he expected conservators to treat it as they would any other museum object, with the same respect for its material integrity. Despite the fact that the bags were deteriorating under the weight of their contents he wouldn’t consider using current plastic bags as substitutes. He had asked the advice of conservators in the past about how to fabricate a work, and said he had likely been useful for a registrar unpacking one of his pieces – being able to re-assure her that two pieces of lumber in the crate weren’t part of the piece, but merely packing material. But when it came to the actual treatment of his work, he preferred to be out of the process.