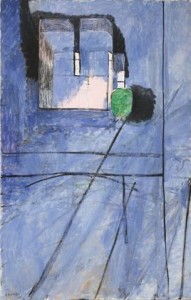

Matisse; Radical Invention 1913-17 at the Museum of Modern Art through Oct. 11 is not for those who take the artist at his word that a painting should be like a good armchair: familiar and comfortable, presumably. Rather it’s for those who like a challenge and find that almost a century later some of his work is still unsettling and disturbing; paintings such as the Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (1914, Philadelphia Museum of Art) defined entirely by scratched lines which radiate like a force field around a sitter who merges with her chair; or the Portrait of Olga Merson (1911, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston) which was seen in Philadelphia in Cezanne and Beyond. Matisse painted a fairly conventional likeness then added heavy black lines that bracket the torso, echoing Merson’s posture but also cutting through her neck, hands, arm and thigh; he also scraped off the right side of her face, as if to re-paint it, then left it erased.

Artists, in particular, are likely to appreciate the close study directed at the artworks by the two curators, Stephanie D’Alessandro and John Elderfield, who were supported by archival researchers as well as a group of ten conservators, conservation scientists and computer imaging specialists, some of whose research is included in the exhibition (and much more in the catalog). The emphasis of this research was on the changes Matisse made as he reworked the compositions, sometimes over a period of years and occasionally radically; this enabled colored recreations of the successive states of paintings and comparisons of various states of related sculptures.

The curators suggest that the process of making a work, evidenced by remnants of earlier attempts at the compositions which Matisse left visible, was part of his subject throughout this period. Hence they reject the traditional term for these: pentimenti. The word, stemming from repentance, or a change of mind, refers to evidence of concealed changes that have become visible because the upper paint layer became transparent with age or because texture from the paintwork of an earlier composition (impasto) shows through the later one; it is now also used to refer to such changes when revealed by radiography and infrared studies. John Elderfield coins the wonderful description of Matisse’s amendatory method of painting and states that while the artist claimed that he desired free and direct painting, his re-workings became part of his creative process and of the resulting work.

I wrote the paragraphs above after spending several days reading the catalog. The exhibition as installed in MoMA is conceived quite differently and is much less explicit about Matisse’s experimental technique. But it offers the same view of the artist’s struggles and his daring with a group of works which reveal a good deal of their making. It also shows Matisse working through ideas across media of painting, drawing and sculpture, as well as his willingness to reject uniformity of paint handling within a single painting (this is particularly clear in The Moroccans) – a characteristic more generally discussed in relation to Picasso’s work.

I was particularly excited to see Bathers by a River (1909-1917, Art Institute of Chicago) after its recent varnish removal and cleaning. It looks splendid! It is one of twenty paintings, many from MoMA’s collection, that have had varnish removed in preparation for this exhibition. This may sound like a minor point, but since the 1880s avant garde artists have preferred matte and chalky surfaces, yet few paintings survived in that state; the more often they changed hands, the less likely they were to have avoided varnishing. This is very apparent in the Copenhagen version of La Luxe, included in the exhibition, painted in a glue-based paint (distemper) and extremely matte; I can’t think of another painting in the medium that has such large areas of un-inflected color, but none of this shows up in photographs. Matisse at times used very thinned, even drippy oil paint handled almost as watercolor and left bare ground visible; these are precisely the sort of effects that disappear beneath varnish, as do areas of blacks with different degrees of richness of paint.

One caveat for exhibition goers: watch your pacing. The works are spaciously laid-out until the last room, which is filled with particularly important work (Bathers by a River, The Piano Lesson, Portrait of Auguste Pellerin, two very abstracted landscapes as well as two of the Back reliefs) and it would be a mistake not to have the energy left to appreciate them. This is an extraordinary opportunity to see a major artist at his most interesting, and not to be missed.