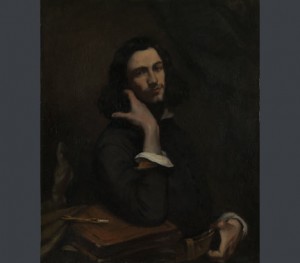

The most sensational aspect of the attribution of paintings as far as the general public is concerned is the subject of fakes, despite the fact that few art historians ever encounter them. What, exactly, is a fake? A painting that appears to be something other than what it is? Not always. Traditional academic training involved copying, and a copy of one work by a student, no matter how close to the model, is not a fake. If a later owner offers the copy as the work of the master, one might use the term fake, providing the owner is aware of the deception. The exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes, Discoveries at the National Gallery, London (June 30-September 12, 2010) included a small painting on board, considered a variant by Courbet of a larger self-portrait painted in 1845-6; it was identified as a copy because the manufacturer’s mark on the reverse indicates a date at least three years after the artist’s death.

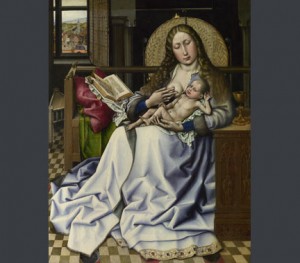

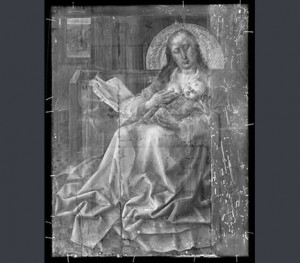

Usually, however, the term fake is reserved for a work created with the intention of fooling the viewer as to who made it and when. Attributions were traditionally made on the basis of visual comparison with other works, but beginning in the first half of the Twentieth Century scientific methods such as radiography and microscopic examination were increasingly employed to add to the art historian’s tools of archival research and visual judgement. The Virgin and Child attributed to Francia (below) was confirmed a fake by a number of technical differences from the artist’s known methods and a laminated panel with old wood on the back so that a simple, visual examination would indicate age. The exhibition brought all the tools of a modern scientific laboratory to examine the status of 37 old master through nineteenth-century paintings in the Gallery’s collection. One of the most interesting points it raised is that answers can be inconclusive, and that the original question, Who made this painting? may not in fact have a neat answer. The exhibition was also remarkably candid about the range of mistaken attributions made by gallery curators and directors in the past, before scientific examination was regularly employed to supplement art historical methods.

Very few artists prior to the Nineteenth Century produced work according to our Romantic notion of the individual creator, isolated from fellow artists and the public. Painting involves craft, and professional artists employed assistants and apprentices to mix paint, prepare panels (which would have been constructed by outside carpenters) or stretch and prepare canvases, and probably to transfer the design from a preparatory drawing. The assistants might also have contributed to varying amounts of the painting as a way of increasing the studio’s production.

As we know ever more about historical workshop practice, the question of who painted a work becomes complicated, since all degrees of collaborative involvement carried the master’s name. ‘A Virgin and Child,’ purchased by the Gallery in 1945 as a Durer is now considered to have been painted by workshop assistants. Scientific examination can rarely distinguish a master’s work from that of his assistants, since they would have employed the same materials and techniques, but this re-attribution was based upon underdrawings revealed through infrared studies which indicated that changes were made throughout the painting’s process, suggesting that multiple artists were involved.

Paintings also change over time because of accidents, in order to modernize them, to fit them into new settings or make them more saleable. The question then becomes what part of the painting was done by the original artist and what changes are later. A painting by a follower of Robert Campin had a broad strip added along the right side of the panel and a narrower one along the top. Examination revealed charring of the original panel, suggesting it had been damaged by fire and the later pieces were added to restore the panel’s original proportions.

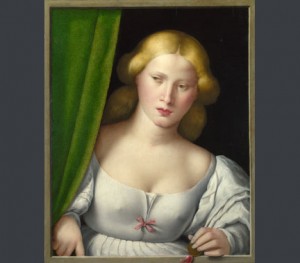

Another painting, of a young brunette at a window, turned out to have been modified to account for Victorian notions of propriety. The blond was given dark hair, her expression was softened and her revealing bodice was altered to hide her nipples. In fact, most 16th century female portraits from the Veneto, such as this one, portrayed courtesans, hence the bleached hair and revealing dress.

The Gallery has an excellent website that functions as a catalog to the exhibition with studies of each of the paintings and associated technical images. It also produced a small book to accompany the exhibition: A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries by Marjorie E. Wieseman (National Gallery Company and Yale University Press: 2010) ISBN 978185709 486 2, which includes somewhat more information than the exhibition labels on the scientific techniques employed in the Gallery’s laboratory. It contains 16 short case studies, most, but not all, of the paintings in the exhibition. Part of the Gallery’s A Closer Look series of short guides, it functions as a useful introduction to scientific examination of paintings (disclosure: I wrote a longer handbook on the physical examination of paintings for art historians, curators, artists, docents and serious museum-goers; it has less detailed discussion of scientific technique but emphasizes the range of art historical questions, well beyond attribution, that can be aided by an understanding of materials, techniques and the condition of paintings).