Anyone concerned with contemporary or post WWII art should get to Washington by Sept. 12 to see this exhibition. Yves Klein is an essential figure in post war art whose work resonates through much of what followed: happenings, performance (and films of performance), installations, minimal and conceptual art. For a current generation of young artists making their way in a world shadowed by the threat of environmental annihilation, his work will have particular resonance.

For many people, situating Klein means reconciling the work with the man: a showman, self-mythologiser and polemecist. Fifty years later those concerns seem beyond the point. The work speaks for itself and coherently, and may well say more than its maker realized. Klein was a young man (the work was produced when he was 27-34 years old) making his way in an adult art world before the existence and sanction of youth culture. And his work is a major inquiry into how to create art in the shadow of the atom bomb, a world in which man had demonstrated an unimagined power of destruction and was further perfecting it. The Cold War may seem a distant memory, but the hysteria of that time was omnipresent.

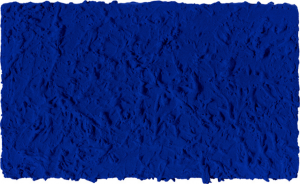

Adorno famously wrote of the ethical obligation of art after atrocities which swept away all previous ideas of culture. Klein responded to the horrors of the bomb, if not the closer-to-home horrors of the Holocaust, by beginning at ground zero: monochrome abstraction. His notes (exhibited) show his concerns with Malevich and Kandinsky; his ongoing mysticism (some of it drawn from communal sources such as Rosicrucianism and Zen Buddhism, some personal) aligns his art with one of the two fundamental justifications of abstraction at the beginning of the 20th century, the other being the analogy with music.

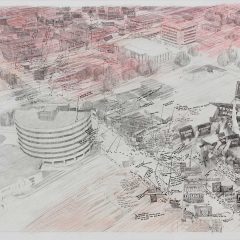

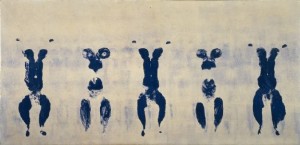

This major retrospective was organized by the Walker Art Center in collaboration with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, where it is stunningly-installed. It is that ideal of an exhibition, greater than the sum of its parts, and although two hundred works sounds superfluous, it is not. While Klein is represented in most American museums that exhibit art of the 50s and later one generally sees but a work or two. To see an entire room of his Anthropometries, Fire Paintings, an assembly of the small sponge sculptures or a large sculptural installation only assembled twice before (in 1957 and 1961) is to gain an entirely different understanding of Klein’s achievement.

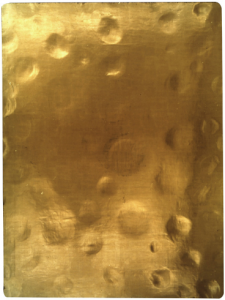

Klein variously explored questions of artistic form, media, permanence and value. The exhibition includes records of his early contractual piece in which the purchaser of a small gold ingot agreed to renounce all its non-material value before throwing the gold into the Seine, and then burning the contract. In a world where art’s value derived entirely from its non-material value (the artist’s ‘value added’ to his canvas and paint, priced according to the market) Klein’s response was, on the one hand, renunciation and on the other hand, to create work using the costliest traditional materials of art: gold and ultramarine (or in Klein’s case, International Klein Blue). His attempt to patent the pigment adds another layer of irony, as the non-material was the usual site of the artist’s work and the art’s identity. His Monotone Silence-Symphony (1949) and the exhibition of the empty space of a gallery, The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, The Void (1958) offered art as a frame for the perception of everyday reality that John Cage would later explore in his 4 minutes, 33 seconds for piano.

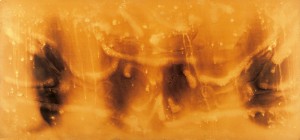

The best known of the Anthropometries were created as monoprints, with the inked bodies of Klein’s models (and in the case of the Hirshhorn’s work, above, the artist’s own body) used as the matrix. Some, however, employed sprayed paint to create silhouettes of the figures. To see these, followed in the exhibition by an entire room of Fire Paintings inevitably brought to mind the silhouetted bodies of people immolated by the bomb that scarred the ground at Nagasaki.

Many of Klein’s paintings, with their delicate surfaces of underbound paint and barely-adhered gold leaf, present major challenges to exhibit; I’m amazed, and grateful, that lenders would let them travel. The smaller ones in the beginning of the exhibition are stiffled by the plexi boxes that encase them, but the large, Monogolds transcend their protective casing; the paintings exhibited free of plexi give a much more accurate view of Klein’s extraordinarily tactile surfaces. But this is a minor problem inherent to the demands of safety. The exhibition is spectacular, and required viewing.

For research on the artist, the Klein Archive has a particularly useful website.

EXPLORING THE VOID

The Centre Pompidou, Paris, Kunsthalle Bern and Centre Pompidou-Metz organized an exhibition in 2009 that used Klein’s empty gallery exhibitions as the starting-point for the exploration of the void that followed. I didn’t see the exhibition and am fairly skeptical about museums’ re-staging time-bound and/or ephemeral art (as MoMA did recently with Marina Abromavic); some art exists only in the moment, and it’s re-staging conveys about as much of it as a specimen mounted on a pin in a natural history museum conveys of a butterfly. But the catalog makes for a very useful anthology of writing on the subject.

Voids: A Retrospective (JRP/Ringier, Affoltern: 2009) ISBN 978-3–3764-017-3 (English edition) surveys the empty exhibition spaces presented by Klein (1958), Art & Language (1966-67), Robert Barry (1970), Robert Irwin (1970), Michael Asher (1974), Laurie Parsons (1990), Bethan Huws (1993), Maria Eichorn (2001), Roman Ondak (2006) and Stanley Brouwn along with extensive illustrations and documentation, artists’ statements, contemporaneous and later published critical writings (including pieces by Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, Brian O’Dougherty, Lucy Lippard, and Robert Rauschenberg), and several new essays. At least thirty authors contributed the essays which are divided into sections covering the Void, Nothing, Vacuity/Empty, Invisible/Eneffable and Rejection/Destruction. More than fifty artists were each offered a page for a response to the subject; some provided texts, others images. While the curators, Philippe Pirotte and Laurent Le Bon, suggested that theirs is only the beginning of an investigation that should be taken further, they have certainly brought together a great deal of otherwise-dispersed material and made the subject readily available to anyone interested. This could certainly be the textbook for a graduate course on the subject.