The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) invited the artist, Virgil Marti, to create an exhibition from works in the store rooms of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), and Marti’s discoveries among the museum’s overflow, dis-attributed, unfashionable, and otherwise overlooked collections were a spur to his imagination. The objects in storage reminded Marti of the final scenes of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, with its panning shot of the endless, largely unopened crates of Kane’s accumulated treasures. In Set Pieces (at the ICA through Feb. 13, 2011), Marti gives previously-silent objects new lives in a sequence of tableaux sprung from his movie-filled memories and dreams. His wonderfully-unorthodox exhibition explores death, memory, art, illusion, museums, and a long history of writing about these subjects.

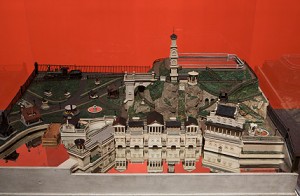

The first object in Marti’s arrangement is a table-top sized model of the Fairmount Waterworks and the reservoir behind it, now the site of the PMA; like all models, it alludes to something else, and the themes of referentiality and illusionism run throughout Set Pieces, where a candlestick refers to a Caryatid; basalt-ware ceramic passes for stone or, when lustred, for metal; and the inlay of a writing-desk features a trompe l’oeil shelf of books.

Circling counter-clockwise, Marti has arranged a group of works illustrating his interest in the uses of artistry to fool the eye. The first is an Austrian porcelain coffee-pot (1795) painted in unlikely imitation of wood, as if it’s exterior were the paneled walls of a room. Affixed to the knotty paneling are two engraved, Italianate landscapes, rendered in such detail that the artists’ names and engravers’ initials are legible, and a slight tear is revealed along the lower margin of one of the prints.

On the wall beyond the coffee-pot is a still life by Abraham Pietersz. Van Calraet of a bowl of peaches. The seventeenth-century painting was certainly intended as a reminder of the fleetingness of life, but the highly realistic fruit and small bug crawling on one peach will also remind some viewers of the earliest writing about painting, Pliny’s Natural History, in which the painter, Xeuxis, demonstrated his skill by rendering grapes so life-like that they fooled the birds.

In a vitrine to the left of the entrance, Marti demonstrates the mute abjection of a group of sculptures as he found them: Claes Oldenburg’s Miniature Drum Set (1969) and Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s Aesop (c. 1906) flank a marble Head of St. John as a Boy (purchased as fifteenth-century by John G. Johnson, but now considered a nineteenth-century fake), brought together by nothing more than their common size and storage requirements.

A delightful arrangement of small bronzes in the second area evokes another story from Pliny. Marti has placed table-top versions of classical statuary and various animals by Barye on a high platform, and lit them so they cast dramatic shadows on the walls behind. These looming shadows are the stuff of children’s games and grade-B horror movies, but the tableau also recalls Pliny’s tale of the origin of painting, when Butades of Corinth’s daughter traced her beloved’s silhouette on a wall, to remember him by.

Marti has found marvelous stuff in the store rooms that are certain to delight any visitor, none more spectacular than Dorothea Tanning’s Rainy Day Canapé (1970), lovers that merge with the couch on which they dally; why the PMA allows this extraordinary work to languish in storage is beyond me. Marti’s free-ranging imagination has animated a group of 18th-century, tilt-top tables that surround the couch, discreetly turning their backs upon the couple en flagrante, while mirrors on the wall behind remind us that we are the voyeurs.

Daniel Buren, in a famous article published in Artforum in 1973, described the Museum as the single viewpoint (cultural and visual) from which works can be considered, an enclosure where art is born and buried, crushed by the very frame which presents and constitutes it. Over the past forty years museums have turned to artists to give new life to their entombed collections, and I freely admit to an enthusiasm for these artist-curated exhibitions. I wrote about the subject, from Andy Warhol at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (1969-70) and Scott Burden at the Museum of Modern Art (1989) to Joseph Kosuth at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (2003) in a post on Jan. 3, 2009. Some artists have used these opportunities to explore museums as sites for artists’ education, others to look at the museum as institutional frame. In 1989 the PMA invited Andrea Fraser to present Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk and Fraser, acting as a docent, chose to highlight the museum’s social functions and rhetoric, rather than its collections.

While Marti emphasizes the imaginative possibilities of work in the PMA’s store rooms, his exhibition at the ICA makes another point: that the identity these objects assume in the museum setting is not their natural one but rather, as Buren might put it, a posthumous identity. In their original incarnations, the objects Marti selected (with the possible exception of the Waterworks model) were domestic accouterments, produced for a middle class wealthy enough to afford them. Their original placement and context would not have been determined by their makers or by the disinterestedness of history (the museum’s usual assumption), but by their owners. They would have been selected according to the purchaser’s taste, wealth and living space (hence the multiple busts of George Washington, in various sizes), and arranged according to the fashion of the day. Marti’s selection is a reminder that, counter to our usual assumptions, we are witnessing the artificial afterlife of such works when we see them in museums.

The ICA has produced a handbook-sized catalog to the exhibition: Set Pieces curated by Virgil Marti from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (ISBN 978-0-88454-119-6). It contains humorous and urbane comments on the selected works by PMA curator Joseph Rishel, articles by ICA curator Ingrid Shaffner, Tom Devaney and Lia Gangitano, and an interview with Marti by art historian Richard Meyer. The design by Purtill Family Business, with its wonderfully blind-stamped frames for each page, poetically suggests Marti’s exhibition as an imaginative frame for the objects and includes numerous details and installation views of this memorable project. The ICA is to be congratulated for its rare habit of producing such catalogs after exhibitions have opened, so that they become serious records of the exhibitions as installed. When the exhibition is itself an artist’s work, this is particularly pertinent.