Post by Deb Miller

Artists have long captured the imagination of writers, and this spring Philadelphia offered several plays focusing on artist as subject, or containing telling references to society’s view of them. The portrayals range from lowlifes and libertines to eccentrics and egomaniacs, to inspired geniuses and avant-garde trailblazers.

Artist as political non-conformist

Two plays, 1812 Productions’ Laughter on the 23rd Floor and BCKSEET’s Losing the Shore, are set in 1953 and refer to artists, albeit briefly, as the antitheses of the conservative period’s reactionary extremes, forced conformity, and appeal to the lowest common denominator.

Laughter on the 23rd Floor is based on the writers’ room of Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, which fell under scrutiny during the McCarthy era. When network executives tell the writers of a popular TV show to stop creating intelligent humor for American audiences, and, instead, to “give ‘em shit,” one responds with the insightful comment, “Maybe if Van Gogh or Goya were wrestlers they’d put ‘em on Saturday night.” For Kenny, the literary wit modeled after Larry Gelbart, artists epitomized the misunderstood geniuses who rose above their times to create high-quality uncensored work that would be respected for posterity.

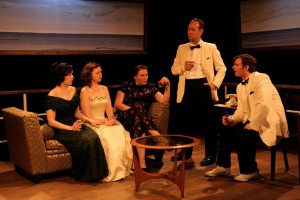

Losing the Shore offered a well-crafted fictionalized account of a cruise taken by Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson in the aftermath of his 1952 presidential defeat by Dwight Eisenhower. Aboard ship, Stevenson’s jilted mistress laments, “Maybe I’ll go to Tangiers and consort with bisexual artists who find me amusing.” This offhand remark, the script’s sole reference to artists, celebrates them as examples of self-expression and acceptance, whose unabashed openness would pave the way to the more liberated Sixties.

Artist as sexual non-conformist

The artist’s legendary world of sexual freedom arose again with the Wilma Theater’s In the Next Room, or the Vibrator Play. Following Doctor Givings’ observation that “hysteria is rare in men,” the extreme sensitivity (and insinuated bisexuality) of lovelorn painter Leo Irving are dismissed with the retort, “Well, he IS an ARTIST!” Later, when Leo is asked if he’d loved many women, he replies with a relative ranking of sexual conquests: “I have loved enough women to paint. If I had loved less, I’d be an illustrator; if I had loved more, I’d be a poet.”

Artists’ affinity with modern women

Set in Paris in 1911, Arden Theatre Company’s Wanamaker’s Pursuit considers the avant-garde circle that would come to define Modern Art: American expatriate writers and collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein; fashion designer Paul Poiret; and Pablo Picasso, whose well-known exploits as a womanizer surpassed those of any poet. The eccentric Gertrude Stein and dissolute Madame Poiret, who has a passionate off-stage fling with Picasso, enjoy a bond with those true artists, for whom “certain rules don’t apply.”

Artist as starving schemer

Along with the tradition of the iconoclastic libertine, the notion of the starving artist remains a commonplace. In Theatre Horizon’s The Credeaux Canvas the Romantic concept is updated to a grungy cramped apartment in New York’s present-day East Village, where three desperate roommates concoct a scheme to swindle a wealthy collector with an art forgery. The story paints a bleak picture of artists, who treat themselves and each other as badly as their intended victim, and endlessly extol the virtues of art, while disparaging humankind.

Artist as doomed egomaniac

People’s Light and Theatre Company offered the most complex and thought-provoking foray into the creative spirit with Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder, in which an aging architect faces his own fading powers and imminent mortality. The protagonist tenaciously denies his talented assistant the opportunities he deserves, and engages in unbefitting flirtations with younger women. In the end, the master builder “can’t climb as high as he builds,” and his refusal to acknowledge that he is not divine causes his own demise.

Not always flattering, these portraits of artists nonetheless make for good theater.