Twenty years ago, when I had just moved to Chicago, Art Chicago was the only fair in the U.S. devoted to contemporary art, and my introduction to the genre. Now that fairs are so common, it may be hard to remember that Art Basel existed only in its home city and New York had many galleries, but no fairs. Art Chicago was then held at Navy Pier, in a charmless state of decay: endless, dirty, green shag carpets that made it clear that the week before the space had held farm equipment, and the following week would likely exhibit motorcycles. The windows at the Pier were missing the occasional pane, so birds flew around over the million dollar Gerhard Richters. There was no better demonstration that art was ultimately merchandise.

Navy Pier was renovated, the fair was occasionally held at other venues, and twice changed hands. It’s now held at the Merchandise Mart which has elegant, Art Deco detailing in and around its elevators and clean spaces for display. As with all fairs, there’s always ancillary and educational programming, and this year Art Chicago asked the College Art Association to organize one of the panels. It made sense to address a current issue, and I suggested that, in the wake of the removal of David Wojnarowicz’s video excerpt from the Hide/Seek exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in November, we address the question of which institutions are able to exhibit art that deals with edgy subjects, and the problems of censorship.

I invited Patricia Hills, art historian from Boston University who has a long interest in political art and whose books include Modern Art in the USA: Issues and Controversies of the 20th Century (and a recent monograph on Jacob Lawrence, which I reviewed on April 3, 2011); Barry Blinderman, director of University Galleries at Illinois State University, who organized David Wojnarowicz: Tongues of Flame, the artist’s first solo museum exhibition, in 1992; and Lauren Rosati, Assistant Curator at Exit Art, a 29-year old alternative space in New York City devoted to exhibiting art that explores environmental, political and cultural issues as a means of initiating or instigating social change (as it says on their website). The panel drew a standing-room only audience.

Pat presented a list of controversial art exhibitions, beginning in 1969 with Kate Milletts People’s Flag Show at Judson Church; she discussed art that was controversial because it dealt with patriotism, revisionist history, religion, homosexuality and the sources of money. She also thinks that a lot of censorship precedes exhibitions, but that subject would have to wait for another talk. Barry began with a short clip from Wojnarowicz’s film; he said it was important, in considering the 11 seconds of controversial imagery within an already much edited version of David Wojnarowicz’s Fire in My Belly, to consider the artist’s entire career. Wojnarowicz’s work consistently addressed martyrdom, communion, cells, time, St. Sebastion, and money, and lamented the loss of spirituality in American life, something the artist found in Mexico. Barry was proud that the exhibition he organized in Normal, IL was described by one critic as an orgy of degenerate depravity.

Lauren Rosati described Exit Art’s almost three decades’ of challenging exhibitions, such as Illegal America (1982), a group exhibition in which each artist had violated the law in creating the art. One of the works was Chris Burden’s Coals to Newcastle (1978) in which the artist, standing at the at the U.S.border at Calexco, CA, flew a small, rubberband-powered model airplane carrying two marijuana cigarettes across the border into Mexico. Exit Art’s exhibitions have included: Dirty Pictures (1982) dealing with sex; Forbidden Films – an historical survey of censorship in films (1984); and Immigrants and Refugees / Heroes or Villains (1987).

The audience at the panel was engaged and anxious to ask questions which, unfortunately, we had no time for. They struck me as more interested in than knowledgeable about art, and I think these opportunities to talk to people less familiar with the art world are crucially important. I urge readers who are offered such opportunities to take them up, enlarge our circle, and let people know the real range of ideas involved in making, selling, studying, writing about and exhibiting art. We have interesting stories to tell.

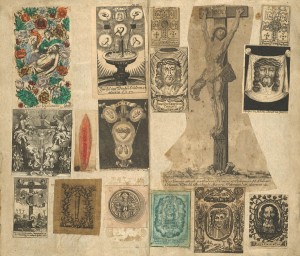

Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life at the Art Institute of Chicago

I had enough time to visit this modest but most intriguing exhibition, at the Art Institute (AIC) through July 10, 2011, which takes a material culture approach, reminding us that before they became art, most old master prints were valued for the information they conveyed or the functions they might serve. These included maps, religious souvenirs (such as those collected in the album, above), wallpaper, faces for sundials and other scientific instruments (below), personal adornment (several fan decorations are on view), bookplates and illustrations in all sorts of books, from the Bible to medical texts; the exhibition includes an anatomical illustration with details that can be turned back, revealing different layers of the body – a very early pop-up book. Prints were also the primary way that knowledge of artwork circulated before photography – hence the many reproductive engravings that informed artists about works they might never see.

While addressing the prints by functional category, Altered and Adorned includes many of the greatest hits of Renaissance printmaking by (or after) the likes of Mantegna, Durer, Titian and Leonardo, and largely in wonderful impressions; the AIC has a splendid print collection, and is the only museum I know that always has prints on view that span the time period of the paintings on permanent display. This exhibition is a valuable reminder of the variety of functions once fulfilled by works assembled under the category of art.

Book Review

In Favour of Public Space; Ten years of the European prize for urban public space (Barcelona: Actar, 2010) ISBN 978-84-92861-3-5.

My airplane reading introduced me to a vast range of imaginative and socially-successful urban projects that have been off my radar. Some are so modest, such as the pocket garden/community center in a passageway in north-east Paris designed by Atelier d’architecture autogérée (AAA), that they may elude the architecture journals. Others, such as the esplanade in Benidorm (above), are off my usual travel routes, and/or in places I never had reason to visit (Zadar, Croatia where Nikola Bašic’ transformed the forlorn seafront on the Adriatic into a sea organ and public gathering space; or Zaanstad, NL where NL Architects created a series of useful, public spaces underneath the elevated highway that cut through the city). Each of the projects has a description of the brief and the process of creating the design, which varied tremendously as to how much the public was a part of the process; all have multiple illustrations and information as to the architects, developers, size and budgets.

So much urban public space in the U.S. is actually private space, such as shopping malls or the parks developers are forced to create in order to get height variances, so it was thrilling to see that a series of European cities, largely neither capitals or cultural centers, value the public and provide first rate architecture for them. The range of the architects’ imagination is also inspiring, and this book will certainly be a welcome source of ideas and information for anyone who loves cities.