by Virginia Maksymowicz and Blaise Tobia

Part 3: Sicily

The railroad from the Italian mainland to Sicily must cross the strait of Messina, bypassing the twin perils of Scylla (a rock formation) and Charybdis (a whirlpool) that challenged the mythical Odysseus. Since there is no bridge, the only means of transport is a ferry. At Villa San Giovanni, the back of the huge ferry opens like the jaws of an alligator, swallowing up the entire chain of carriages. At Messina, the front end opens and the train is spat out onto a set of tracks on the other side.

So began our most recent visit to a land filled with mythology, music, food and art (mostly very old). Blaise’s ancestry lies in this area of the world, in the small town of Calatafimi, known for its beautiful Doric temple Segesta and for having been the site of Giuseppe Garibaldi’s first battle for the unification of Italy.

We don’t normally expect to see much in the way of great contemporary art in Sicily. For one thing, it is relatively isolated and relatively poor, in comparison with the Italian mainland. For another, the island is so filled with history that there isn’t much room for anything new. We typically use our time in Sicily to appreciate its great natural beauty, to learn about its culture, and to observe how it is being inexorably drawn into the (post-) modern world. On this trip, however, we were pleasantly surprised by a number of encounters with contemporary art and with efforts to use some of Sicily’s rich architectural patrimony in support of living artists. We also saw energetic and intriguing street art in Sicily equal to that found farther north.

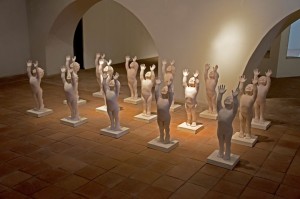

Indeed, it seems that every Sicilian city or town has more castles, churches, palaces and government buildings than it knows what to do with. We discovered one remarkable re-purposing of such a space in the island’s second largest city, Catania (which lies in the shadow of Mt. Etna with its main boulevard paralleling an ancient lava flow). As we were walking around its historic center, we saw a large banner hanging from the façade of a palazzo, advertising an exhibition of “therapeutic” sculpture. Intrigued, we entered a former convent that had been transformed into a cultural center, Palazzo della Cultura. Inside, we saw an installation by the Sicilian artist, Orazio Coco, “L’esercito della speranza” (The Army of Hope). Although this body of work had been shown previously, this particular adaptation to the specifics of the ex-convent was brilliant. Consisting of ceramic cast sculptures modeled on his own children, armies of replicas were fitted to each room in ways that dialogued with the architecture. We met Orazio and his family, and asked about his use of the term “therapeutic.” In a nutshell, he believes that art has the power to heal not just individuals, but societies. As a young father, he is convinced that, in their innocence and primal emotions, children have much to teach the adults of the world.

Another remarkable architectural transformation we encountered was in Palermo. A large former factory complex (of twenty-three separate buildings) has become an arts center called the Cantieri Culturale alla Zisa—the cultural workshops at the Zisa castle. This complex had peaked in its industrial output during the early 20th century and then declined until it was closed in 1968. Under the leadership of Palermo’s visionary mayor, Leoluca Orlando, the city acquired the property and restoration has slowly been taking place. Some of the entities in the Cantieri are the Goethe Institute, the Palermo National Film School, a cinema, the photography and sculpture facilities of the Palermo Academy of Art, and ZAC (Zisa Zone Contemporary Art), which had just opened a few days before our arrival.

We met with Professor of Sculpture, Glauco Bertola, and Chair of Photography, Sandro Scalia, and were able to tour their new facilities. The transformed factories are spacious and well lit, but—perhaps even more so than in U.S. art schools—the programs are severely underfunded.

Fabrication equipment for sculpture was almost nonexistent and only a few cameras, lights and computers were being shared by five hundred photo students. As in the U.S., the teachers must struggle to keep up with their own artmaking. We were impressed with Sandro’s work, especially his book Le Città di Palermo: Cities within the City.

The establishment of the Cantieri Culturale has spawned a burgeoning artists’ community in the surrounding neighborhood. We happened upon the studio of Georges Bilé, a painter from the Ivory Coast, who invited us in to see his work. A very affable man, he was working away while minding his young son. His oeuvre is expansive, ranging from his own landscapes, portraits and abstractions, to copies of anything a client might want.

In 2006, we had tried to see Palermo’s Museo Pitrè, a folk art museum housing the collection of Giuseppe Pitrè, the most well known ethnographer of Sicilian folk culture. We had checked the hours on the web and arrived at the complex that includes the Palazzina Cinese, a fantastical “hunting lodge” commissioned by the Bourbon King of Naples and Sicily, Ferdinand IV. But we found it closed. “In restauro” (“under renovation”) the sign said. We returned in 2010. Still in restauro. This time around, unable to find out anything definitive on the Internet, we decided to try visiting a new branch of the museum, in the Palazzo Tarallo, located in the midst of the historic Ballarò market downtown. As the old saying goes, the third time’s the charm—it was open!

We were greeted at the entry by an enthusiastic guard who accompanied us into the exhibition space. As we were looking at documentary photographs of Palermo’s great festival of Santa Rosalia, two more museum employees joined our group. (We were the only visitors to the museum and were Americans to boot!) We entered the final gallery, in which there was a room- size installation as part of an exhibition riffing on traditional Sicilian puppets, “Teste di Legno” (Wooden Heads), by contemporary sculptor, Roberto Lo Sciuto. At that point, the museum director, Tonino Pitarresi, joined us as well. Conversation ranged from the sculptures to the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution (the shootings at Sandy Hook had taken place a few days earlier).

Before we knew it, we were whisked upstairs to see their library, an incredible collection housing not only Pitrè’s books and manuscripts, but also a variety of other ethnographic resources. Ida Zammarano, the lively and knowledgeable librarian, pulled out all sorts of photographic tomes for us to see, including the work of Melo Minella.

Two days later, we did finally make it into the main branch of the Museo Pitrè, as well as the Palazzina Cinese, the restoration finally completed. Only a small fraction of the collection was on display, but it was well worth the visit.

On this trip we also made it to the GAM (Galleria d’Arte Moderna) in downtown Palermo. Like the Pitrè, it had been in restauro when we had visited the city in 2006, but it had opened to the public later that year. Housed in the former Franciscan convent of Sant’Anna alla Misericordia, the permanent collection includes a few well-known Italian artists like Giorgio de Chirico and many lesser known, but nonetheless notable, artists like the sculptor Giovanni Nicolini. There is also a gallery serving as its temporary contemporary. A mixed-media installation called “An Artful Confusion” by Francesco Simeti was on exhibit. The Palermo-born Simeti splits his time between Sicily and Brooklyn (and his wallpaper-style collages can be seen along the platform of Brooklyn’s 18th-Avenue station on the D-line subway).

We found a third example of re-purposing for the arts in a very unlikely setting—the rural town of Salemi. A few years ago, its then mayor, the visionary Vittorio Sgarbi, had announced a program intended to reinvigorate his economically depressed and depopulating little city. He offered a house for just one Euro to anyone who would move to Salemi. (Most of these houses had been abandoned after a serious earthquake in 1968.) Sgarbi, who is not Sicilian and who majored in art history at the University of Bologna, had served as culture minister under Silvio Berlusconi. He was especially interested in attracting artists and might have been inspired by yet another visionary Sicilian mayor, Ludovico Corrao, who had moved his entire town of Gibellina after that same earthquake, attempting to reinvent it as an international city of art.

One person who took up Sgarbi’s offer was a Korean named Youngman Kim. Kim had originally immigrated to New York City, where he opened a video rental business on St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. He eventually amassed a video archive of more than 55,000 films, some of them rare and out of print. (Many regard it as an extremely important resource for modern and contemporary American cinema.) Four years ago, a story appeared in The New York Times indicating that Kim—having become a victim of Netflix, internet streaming and rising rents—was being forced to close his doors. Subsequently, Kim somehow learned that Salemi— definitely on the margins of contemporary culture—wanted to be supportive of the arts. He arranged to ship his entire archive there. Three years later, with no apparent progress, the LA Weekly ran a story casting doubt upon the fate of his collection.

What the LA Weekly writer failed to understand is that Italy is Italy (Sicily even more so), and everything is more nuanced and layered that it seems on the surface. Local townspeople can still be suspicious of strangers. The passage of time is certainly calculated on a different scale. We found that the Centro Kim, as it is called, did indeed officially open in September. The local newspaper, Il Belice, describes how Kim has been working with local high school students to digitize the extensive collection. It still remains to be seen whether it can contribute to the revitalization of its adoptive home.

While the international contemporary scene does not reach into many parts of Italy, there is, nonetheless, a vital and living practice of art in everyday life. It is often discounted because it is hidden in religious and folk traditions. Three of our most memorable “art” experiences during this trip did not take place in galleries or museums.

One of these experiences was participating in a procession in Calatafimi celebrating the Immaculate Conception. This religious festival is only about 150 years old but its manifestation clearly has roots in pre-Christian antiquity. This grand performance artwork started with a loud chorus of bells at 4:30 AM on a cold December morning. A flower-decorated statue of the Virgin Mary was carried for hours throughout the streets of the town by enthusiastic young adults chanting loudly in Sicilian, in an eerily evocative cadence. Their way was lit by hundreds of people carrying four-foot long bundles of burning reeds.

A second religious procession, in the city of Siracusa, was amplified by a healthy dose of civic enthusiasm. Ten thousand people, many of them barefoot despite the cold, walked through the streets of the city with a statue of its patron, Santa Lucia, accompanied by a municipal marching band. The statue itself, larger than life and covered in silver, is an amazing sculptural artwork. It bears a striking resemblance to an earlier statue—one of Athena, who was a kind of “patron saint” to Siracusa in the Hellenic era, when it was the second greatest city of Magna Grecia after Athens.

The third was truly a work of performance art, involving about 150 people gathered at a beautiful grotto in the side of a marble cliff near the quarry town of Custonacci. These people come together for six nights each year, in late December, to create a living presepio. (Think Laguna Beach Arts Festival meets Colonial Williamsburg.) In the deepest recess of the cave, a few of them silently enact Mary (holding a wooden Jesus), Joseph, and shepherds, surrounded by live domestic animals. The rest portray traditional Sicilian life in all its variety.

Whether it is in manifestations like these (and no contemporary performance art is better) or through the meticulous building of Neapolitan-style presepi, brick by brick, Italy reminds us of why the human need for artmaking endures. It is proclaimed in the words engraved over the portico to Palermo’s Teatro Massimo: “Art renews the people and reveals life to them.”