[Ed. note: In celebration of artblog’s 10-year anniversary, we are bringing you content from our inaugural year, 2003. July, 2003, was a month when we had a lot of contributions by local artist/writers like Judith Schaechter, Eric McDade, Franklin Einspruch, Samantha Simpson, Gerard Brown, Sid Sachs and others. Below is a sample a short back and forth about nostalgia and its meaning for contemporary art.]

And now a word about something old

Post by Gerard Brown

Originally published on July 19, 2003

This has nothing to do with anything y’all have been talking about, as interesting as it all has been….

But could someone (preferably an artist with real thoughts on the subject) please explain the allure of the old to me? At an artists’ talk at Vox this evening, listeners were treated to rapturous soliloquies on the merits of “old” pornography and “old” video games[image of Atari joystick]…is there something inherently corrupt about the SIMS that no one is telling me about? Should I only visit vintage porn sites if I’m really arty in Philadelphia?

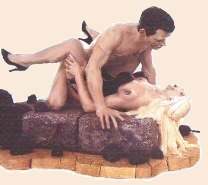

Part of what I’m getting at (f you haven’t noticed) is whether historical distance is a signifier of authenticity that can be – at the end of the day – trusted. Is making art from contemporary porn (in the manner of late 90’s Jeff Koons–[image is one of Koons’s “Made in Heaven” sculptures from 1990) inherently less interesting? Is the Atari version of Space invaders somehow innately more compelling than Super Mario or Lara Croft (see Miltos Manetas for an argument on this subject)?

Help! I await y’all’s thoughts…

many thanks,

Gerard Brown is a Philadelphia artist and writer who teaches at University of the Arts

The good old days

Post by Judith Schaechter

Originally published July 21, 2003

Hi Gerard–

I just read your post–and I’m wondering, respectfully of course!, if perhaps you’ve contorted yourself into a pretzel knot over this one. I wasn’t at the talk at Vox you mention, but it’s my impression that a fetishizing of the old has something to do with nostalgia (sentimental feelings about the good ol’ days–probably a psychological necessity because in many, many ways, the good ol’ days sucked and if we actually had to face up to that we’d all commit suicide).

[It also has to do with] a sense of preservationist imperative (i.e. things are going so fast–let’s not throw out the baby with the bath water in our mad rush towards a brighter future. Preemptive nostalgia?)

Anyway, my point is that fetishizing the “old”, smarmy as it can be, serves an important function.

With regards to the relationship of the “allure of the old” to “authenticity”–I’d say, emphatically, it’s not much of a relationship.

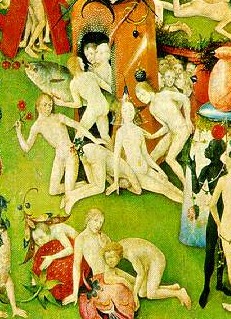

[Art’s] all about FANTASY, baby [see image, “Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hiernoymus Bosch]. Fantasies of the past and of the future. We already have a signifier of authenticity (is that another word for “reality check”?)–it’s called sanity–why burden ourselves with more of that?

It’s my most unhumble opinion that in the arts, fantasy trumps reality (imagination trumps intellect, artifice trumps authenticity, “art is a lie that tells the truth”, blah blah blah, yadda yadda yadda, etc etc.) every single damn time.

Judith Schaechter is a Philadelphia artist and writer known nationally for her work in stained glass.

Bad hair, vintage clothing

Post by Eric McDade

Originally published on July 21, 2003

Is making art from contemporary porn inherently less interesting?

No. But it seems that folks are more threatened by contemporary porn than “old” porn.

[Porn’s] primary purpose is undeniable and unshifting: it is simply pornography. Since contemporary porn is so [single-minded] in its societal function, its use within artwork can be problematic in that it, porn with a capital P, can tend to overshadow the artwork.

The stigma, taboo and general controversy surrounding contemporary porn holds too much baggage for many viewers to filter through. However, given historical distance, porn becomes (forgive me) less potent and controversial; its role becomes more malleable.

How?

I’m not so sure that historical distance is necessarily a signifier of authenticity. I’m more apt to think that it serves as a diminisher of taboo, rendering the once socially repellent or morally bankrupt (by mainstream conservative standards) pedestrian, even public domain.

[Woody Allen’s definition of comedy has some relevance here.] For as much as Woody Allen (shown) intended it to reinforce what a pompous ass Alan Alda’s character was in “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” his explanation of the formula for comedy (comedy = tragedy + time)actually has some relevance. And I believe porn is an arena affected by time much the same way tragedy is.

Compared with today’s porn, vintage porn appears tame, even a bit goofy, and eventually falls into the realm of kitsch (sorry about that). The forbidden element is softened and becomes the focus of teasing and laughter rather than fear and condemnation. Often, the impetus for this laughter is the most socially accessible target offered by the past: its clothing and hairstyles.

By focusing first on what we normally ridicule when looking through our own family albums, the sexual acts and posturings become secondary, thereby diffusing a once-threatening entity and rendering it as safe and neutral as any other medium.

Eric McDade, a Philadelphia artist, has two paintings in the Space 1026 show up through July 25.

Preemptive nostalgia

Gerard responds to Judith

Originally published July 22, 2003

Judith, as usual, you have a thoughtful answer to whatever I’ve baked my noodle on at any given moment.

I think I’m drawn to the notion of “preemptive nostalgia” as it includes some of the snobbery that I hear in any statement [about] the good old days…and what better fantasy can there be than to go back in time and make the world into a better place than it is now? So much easier than working toward a better future.

Gerard Brown

My nostalgia is your rubbish

Post by Samantha Simpson

Originally published on July 24, 2003

There’s something more at work in the phenomenon of nostalgia than you’ve mentioned here, although I agree with what you’re saying about the sanitizing aspects of time on difficult material. The aspect of the dialogue that I’m interested in is the appeal of Atari as a subject for nostalgia. There are certainly ways in which this works like any other kind of nostalgia- Atari can be read as a symbol of a technological childhood or as a tool to imagine a culture that was technologically naive.

For a generation slightly younger than me, atari was a first experience of the wonder of technology. I remember feeling something similar to what I imagine they felt about atari when I was about five years old watching the first digital clock my family got flip over the cards that miraculously told the time without a round clock face. Atari has limited nostalgia value to me, but I have great affection for the early text based computer games I played on the mainframe computers at my dad’s office, and I’m all over Dig Dug.[See image.]

The production of nostalgia, though, is particular to each generation, and I have begun to think it’s predictable. I suspect that you can figure out what people will be nostalgic about (to a certain extent) based on their age. Nostalgia for products serves to form a community identity, and if you’ve ever seen a group of people talk about an old TV show that’s no longer on TV, you’ve watched people form bonds over a common groundof childhood pleasure that’s quite powerful.

Ask a college student about Alf or Fraggle Rock. Strawberry Shortcake & My Little Pony, if they’re a little older. Ask my generation about Fantasy Island, Love and Rockets, adidas, and Mr. Zogg’s Sex Wax t-shirts. It’s not that these things stand the test of time; our nostalgia serves as a shorthand way of sharing a sense of ourselves as children. Remembering how freaked out I used to get when Mr. Rork (sp?) got the scary magic eyes is funny because it marks a passage of time- I can laugh at how simple I was back then, and I can expand my own dumbness to imagine a culture in childhood. I can think I was young in a time that had such dumb TV as will never been seen again, blissfully ignoring Charmed and Touched by an Angel, which will no doubt become the embarrassing subject of a new generations’ nostalgia.

There’s also a much better, more creepy explanation for this phenomenon in Michael Thompson’s 1979 bookRubbish Theory and in Arjun Appadurai’s work. Both talk about commodity theory- Thompson’s book elucidates the way commodities move in value over time. Thompson says that objects have a life cycle of value. First they’re new, rare, and exciting. Valuable. Then they saturate the market to greater and greater degrees and lose value. Then they become so out of fashion that they become invisible. No one thinks about them, they’re totally dismissed. They become trash. Many of them get thrown away. Then some collector finds one, thinks they’re rare and neat, publishes something to that effect and they gain cultural value at a way higher status than they ever had. Atari certainly went through that cycle. I’m looking for barrettes with ribbons hanging off the ends any minute now.

I think that’s what’s driving the fashion for flat, pixelly grahics, too; it’s a mini retro craze for low tech high tech. (Check out flipflopflyin.com for a master of the big pixel.)