(Andrea review three books with gorgeous photographs and interesting content, all great gift books for your arty reading loved-ones. –the artblog editors)

Awakening the Night; Art from Romanticism to the Present (Del Monico Books, Prestel, Munich: 2010) ISBN 978-3-7913-5260-2

This catalog to an exhibition at the Belvedere Museum, Vienna is particularly appropriate for the year when everyone is celebrating Edgar Allen Poe, whose most famous work is set Once upon a midnight dreary. It addresses the wide-ranging subject of nighttime, in paintings, drawings, prints and photographs, primarily by European artists, with a few Japanese works, and a handful by contemporary, Americans. While, during the 15th-17th centuries, artists usually painted night scenes, such as the Flight From Egypt or a night-time Adoration, as an exercise in virtuosity, since the early Nineteenth Century the subject of night has carried a range of associations: of love and war; sleep, dreams and somnambulism; nocturnal activities, from nightlife to sex; the underworld; and sublime landscapes. The almost 300 works in the exhibition are overwhelmingly the descendants of Goya’s sleeper, on the title page to Los Capriccios: Enlightenment man, whose dreams produce monsters.

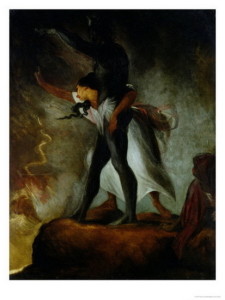

Multiple authors discuss subjects from allegory and psychology to technology and military history, but the interest of the book is likely to be the illustrations, which are all in color. I’ve rarely encountered a group of European work from this period that contains so many surprises and unknowns. I’d expect an exhibition on the subject to include Max Klinger and Henry Fuseli, but would not have anticipated Fuseli’s abolitionist subject from William Cowper: The Negro Avenged (1806). While it’s interesting to see another Klimt, of a mother and two children in bed with nothing but their heads visible, as if floating in a nighttime sea of blankets, the National Gallery of Art, D.C. owns a related painting of a baby all but obscured within a mound of quilts. It is much more interesting to discover Caspar David Friedrich’s Clouds in the Evening Sky (1824), a rarely-reproduced, figure-less landscape in which a jagged band of white clouds bisect the painting diagonally. The last two, and the majority of the paintings in the exhibition, are from the Belvedere’s collection. This suggests that Freud’s interest in nocturnal thoughts was widely shared by generations of Viennese artists and collectors.

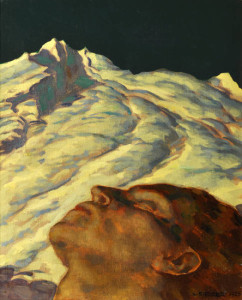

The catalog is a fascinating reminder that the reputations of many interesting artists have remained regional. Among the surprising discoveries are Michael Johann Neder’s Return of the Herd (1844), a visually striking work, despite its nostalgia for rural life and slightly naive draughtsmanship; Karl von Diefenbach’s lurid landscape, with lighting effects that prefigure film; Joseph Floch’s People on the Street (1919), painted with a subtle use of color and Kokoshka-like brushwork; Hugo Scheiber’s somewhat abstracted City Lights (1919), a portrayal of the excitement of urban life that pre-figures Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie; an hallucinatory, purple landscape by Marianne von Werefkin; the exaggerated viewpoint of Karl Sterrer’s Mountain Dream (1925), that resembles experimental photography; and the contemporary photographer and filmmaker Lisl Ponger, who captures lighting effects similar to those of Edward Hopper. This volume offers ample treasure for anyone who enjoys discovering the unknown and expanding the catalog of one’s visual memory.

Michael Govan and Christine Y. Kim James Turrell; A Retrospective (Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Del Monico Books, Prestel, Munich: 2013) ISBN 978-3-7913-5263-3

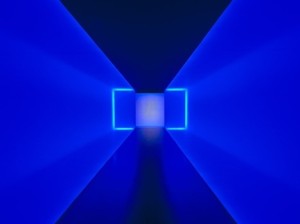

The jacket to this catalog of a traveling exhibition, initiated by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, truly glows. I don’t know enough about printing to say how, but it was carefully planned to suggest the effect of some of Turrell’s installations, in which he creates forms with no actual boundaries, and spaces that might be actual or might be illusory. The artist is surely some sort of magician, and the catalog does justice to his work, which is lush, precise, yet often ephemeral. The designers, Lorraine Wild and Xiaoquing Wang of Green Office, clearly thought a great deal about their subject, and designed a beautiful volume that is substantial enough to capture the ambition of an artist who has sited his ongoing and most important work, Roden Crater, within the remains of a spent volcano.

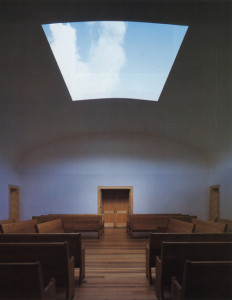

No one is more sensitive to the effects of changing illumination than James Turrell. Much of his work consists of structures that are not themselves art, but are frames through which natural, ambient light effects can be observed. Even with his installations involving manipulation of artificial illumination, the lighting sources are only the mechanism which produces the work, the material of which is light itself, or as the artist has said, the perception observers have of that light. His is the ultimate de-materialization of the art object, as well as the transfer of creation from artist to viewer.

My only hesitation about the book concerns the inevitable distortion of artwork in reproduction. It is hard to know how a reader who has never experienced Turrell’s work will understand the photographs. The illustrations of the sky lights inevitably suggest that the architecture is the artwork, and the light installations that use fluorescent or xenon lighting maybe difficult to distinguish from the debased, commercial uses of similar lighting. But if one wants a book that records the career of an artist whose subject is perception, this is absolutely the best possible solution.

Catherine Legrand Indigo; The Color that Changed the World (Thames and Hudson, New York: 2013) ISBN 978-0-500-51660-7

This sumptuous book can be appreciated on several levels: a history of the production and trade of dyes and textiles; an anthropology of textile production; and a stunning visual catalog of the international production of cloth colored with the blue dye, indigotin. The dye is most readily obtained from plants of the indigofera family, grown extensively in India (hence the name, indigo), but can also be extracted from a number of other plants, at least some of which are grown on every populated continent. Indigo is truly a universal blue.

Legrand documents her world-wide travels to visit areas where traditional methods of extracting the colorant and using it in textile production have been maintained. She shows pictures of farmers, dye-makers, dyers, weavers, and a great array of the blue textiles that resulted. They include blue denim, French toiles, Japanese tie-dyed (shibori) and resist-dyed fabric (much of it ikat, or woven fabric where the pattern comes from specially-dyed yarns), the shiny (calendered) cottons worn by Miao, Dong, and other traditional villagers in China, India’s block-printed cottons, resist-dyed adire cloth of the Yoruba, and the woven cottons which Mayans use for skirts, huipils (blouses, tunics or dresses), and shawls. The volume includes a list of museums with significant collections of indigo-dyed textiles, a list of workshops and producers of traditional dyes and fabrics, and a bibliography.