[In this post sponsored by the West Collection, Christian Viveros-Fauné explains how sculptor Long-bin Chen gives new life to a sometimes-devalued medium: books. — the artblog editors]

“You cannot open a book without learning something.”

― Confucius

The late Susan Sontag had it right: “A good book is an education of the heart.” Not only do books enlarge one’s “sense of human possibility,” she wrote, they also expand the individual’s “experience of the world.” Conversely—the great American cultural critic declared—books are “creators of inwardness.” It doesn’t take a huge imaginative leap to believe that, had she been asked, Sontag would have easily extended her observations to choice bits of music or objects d’art. That goes double had she ever been confronted with Long-bin Chen’s bookish busts of classical composers.

An artist who has taken to carving bizarrely realistic sculpture from the detritus of our machine-age civilization, Long-bin Chen has for more than two decades turned the old modernist idea of truth to materials into a capacious digital-era sculptural metaphor. As the artist put in an interview, it was sometime in 1992 that he realized that the personal computer had begun making the world of books effectively obsolete. Not long after, he began cutting up hard and paperback volumes, newsprint, and recycled paper. The results are trick-the-eye sculptures that represent modernity’s most fundamental changes. Memorials to the written and printed word, Chen’s strangely readable forms point up how we understand, package, and consume information in our technologically driven, data-obsessed, post-literate new millennium.

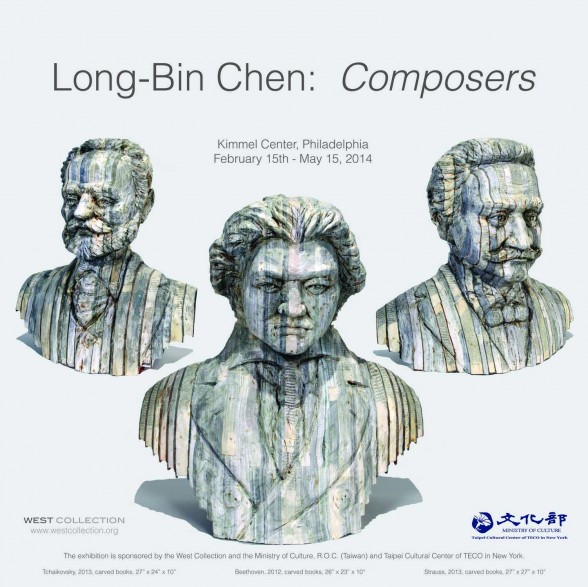

Chen’s most recent suite of sculptures features the heads of some of the world’s greatest classical composers. Knifed, machine sawed, and carefully sanded from books gathered from his own and other “found” libraries, Chen dutifully crafts each of his busts to resemble likenesses straight out of history books. The fact that he has learned to brilliantly transform his chosen material adds greatly to their uncanny effect. Rather than betraying their origins as mostly discarded paper products (the artist often salvages tomes from bookstores, publishing companies, and university libraries), his carved heads—with their noticeable grooves and striations—appear as if they’ve been chiseled from noble materials like hardwood, marble, or stone.

Chen’s sculptures activate an age-old audience reaction that can prosaically be termed “the whipsaw effect.” An artist who has become expert at making everyday stuff look new again, his representations of the familiar look conventional, but only at first glance. Take, for instance, Chen’s latest choice of subject matter. Titled simply after the names of giants of the Western musical canon, sculptures like “Bach,” “Beethoven,” “Brahms,” “Chopin,” and “Verdi” present their subjects in the form of classical statuary, but with an additional visual-rhetorical twist. Instead of being merely constructed from traditional materials or even their paper facsimiles, Chen’s busts are ultimately made up—to borrow a line from the equally canonical Hamlet—of “words, words, words.”

And therein lies the lasting strength of Long-bin Chen’s art—namely, that the Taiwanese artist doesn’t just make certain time-tested traditions look new again, he refurbishes their cultural currency. Riffing on academic sculpture, his classical-looking busts update past and present artistic traditions, while making the case for a renewed kind of cultural literacy: one capable of carrying the values of visual art—and books and music—far into the future.

— Christian Viveros-Fauné