[Jennifer digs into Cézanne’s labor-intensive approach to art-making, and dedication to certain still life subjects–both of which set the artist apart in his rapidly industrializing era. — the Artblog editors]

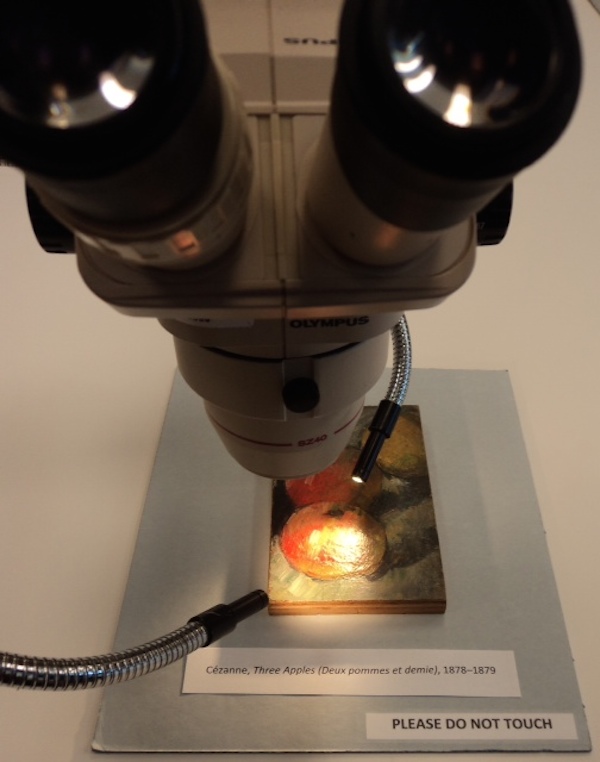

In his essay titled “Cézanne’s Doubt,” Maurice Merleau-Ponty tells us that it took Paul Cézanne “one hundred working sessions” to complete a still life. Last Tuesday, under a high-powered microscope in the Barnes Foundation’s light-filled conservation lab, it seemed that all the layers of paint applied in those 100 sessions were revealed.

The microscope’s lens was focused on a small painting titled “Three Apples,” 1878-1879, temporarily removed from its usual location in a Barnes wall ensemble in gallery three, and available for study at a press event in support of The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cézanne. This special exhibition opened at the Barnes on June 22.

Uncovering the artist’s effort

“Three Apples” is exemplary of Cézanne’s impasto, and also of the subject, focus, and working methods found in the 21 still-life paintings on view in The World Is an Apple. The Barnes’ large special exhibition space allows for liberal intervals and pauses between works. There is plenty of breathing space in which to consider the intensity of Cézanne’s painted surfaces and his radical approach to making a painting.

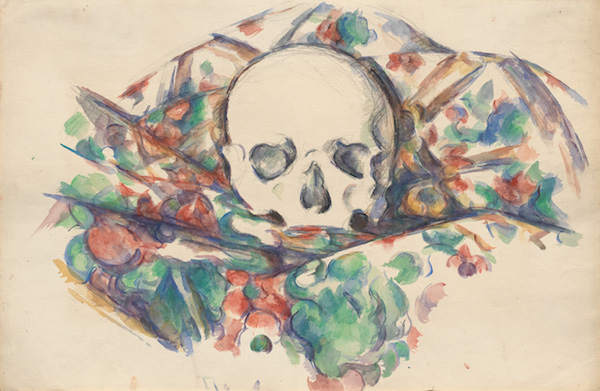

The famous apples, provincial furniture, skulls, faience, water jugs, and mountainous swags of fabric are all here. These props are the “main characters,” as the exhibition curators call them, of Cézanne’s still lifes and his identity.

The pottery and furniture originate from the vernacular craft industries of Aix-en-Provence, where Cézanne lived and worked. Catalogue essayists describe how these items are revelatory of an artist whose work and consciously constructed self-identity were allied to a regional and pre-industrial way of life that was threatened by increasing mass industry. Cézanne’s famous, and very obvious, constructive brushstrokes communicate laborious handcraft at a time of industrial expansion.

Set apart by subject matter

These brushstrokes are also a key to appreciating some of the ways that Cézanne “broke all the rules,” as Barbara Buckley, Barnes’ head of conservation, said. In the still lifes, we see an overall surface pattern created by repeating brushstrokes that simultaneously depict and differentiate unique objects. How can an apple, a table, a piece of fabric, and a section of patterned wallpaper appear to be such independently separate and recognizable things when they are all painted using the same demonstrative brushstroke, the same materials, and often, the same colors?

Cézanne builds autonomous forms while connecting all forms to each other. His was an experimental and radical approach to painting in the late 19th century, when conventions called for perspective, illusionism, and clear figure/ground delineations.

Still life was the genre in which Cézanne could be his “most experimental,” as curator Benedict Leca writes in his catalogue essay. The 21 examples here, out of nearly 300 still-life paintings made over the course of the artist’s career, shape our understanding of these apples, ceramic vessels, and skulls as deeply subjective choices for an artist who worked tirelessly, writes Leca, to “define himself and to diffuse his constructed identity through his paintings.”

Framing his own future

The great strength of The World Is an Apple is that it positions Cézanne not merely as the provincial, melancholic misanthrope as we have come to know him from the earliest critical appraisals of his work, but as a savvy, crafty artist who engaged with still-life painting and rebellious approaches to art-making in order to secure a reputation as a legendary master.

These 21 works complement and further illuminate the 69 Cézannes in the Barnes Foundation, 16 of which are still-life paintings. An augmented audio tour featuring Cézanne works in the Barnes’ permanent collection is available through the duration of the special exhibition.

The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cézanne is on view at the Barnes Foundation from June 22-September 22, 2014.