[Evan, who has been walking a lot lately, explores another group show set between spaces–one that’s meant to open our eyes to the many different meanings of “home” and place. — the Artblog editors]

Itinerant Belongings, the latest collaborative exhibition between Slought Foundation and the University of Pennsylvania, endeavors to explore the physical and immaterial natures of belonging and home through a mixture of photography, video, and drawn imagery. Highlighting the plight of homelessness and its evolution over the past few decades; the effect of a growing homeless population on our definition and delineation of public and private spaces; and the social rituals and tropes that have been forged by these conditions, the exhibition takes place concurrently at two spaces: Charles Addams Fine Arts Hall at the University of Pennsylvania, and Slought’s gallery and exhibition space. This dual existence requires a physical as well as mental trek from space to space, an action that organizers Iggy Cortez and Charlotte Ickes confirmed was intentional–the idea was to ensure a nomadic transition in accordance with the struggles of the subjects of much of the work.

By nature, photographic images can be both literal and extremely abstract–each image’s presence confirms the existence of its subject and their condition, but can also have the effect of isolating the subject, or altering the viewer’s interpretation of context and identity according to the photographer or videographer’s gaze. As such, the exhibition’s reliance on captured imagery creates a productive duality of documentary utility and social activism.

Accessibility through media choice

One of the greatest successes of the endeavor is the choice to present work that dates back to the 1970s and up through today, as well as pieces by many international artists, confirming the relevance of the exiled and the ever changing definitions of nationality, patriotism, and homecoming.

If there is one trap that the show falls into, it is the loftiness of its ideas and execution–it is clear that it was created by academics and intended for display and discussion within academia. It is not an easily interpreted project, and I can see the need for thorough exploration and frequent reference to informative materials as being discouraging for some viewers.

For this reason, I see the choice to use video and photographic work as the show’s saving grace. By using media that are consumed and distributed daily by the general public, the organizers help to round out some of the immediate hesitancy that formal paintings, prints, or sculptures concerning the same themes might evoke in the passing viewer.

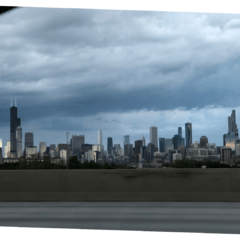

I first visit Slought, which is a noticeably dark space. Projected onto the far wall is Israeli-born artist Yael Bartana’s “Trembling Time,” a hypnotizing loop of passing cars on a freeway as viewed from a fixed, elevated position. As the viewer is lulled into the normalcy of the scene, the cars eventually come to a halt, at which point their occupants exit and stand motionless for what seems like an eternity. After a time, they again enter their vehicles and move along.

The piece is an examination of nationalistic group identity and the ease with which we slip into our determined roles, accepted rather than deliberated. The passengers’ pause and confrontational gaze are a quiet declaration of solidarity with those who ask, “What are we doing? How does our compliance affect our collective condition?”

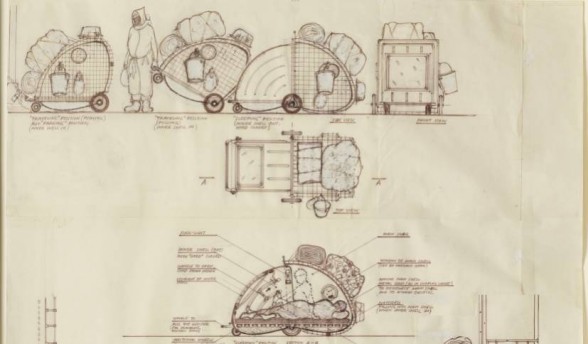

A number of other works hang from the gallery walls, notably those of Krzysztof Wodiczko, a Polish artist who, among his many other projects, created homeless vehicles–multifunctional and transformable carts that served every need from lavatory to enclosed sleeping space. The works were realized in New York City and Philadelphia in the 1980s, and Wodiczko then documented their use and reception through still photographs (he chose to use mostly the work from New York, and his Philadelphia experiments have gone largely unpublicized). The drawn studies for these functional contraptions are aesthetically beautiful and Da Vinci-esque in their illustrative inventiveness.

His work empowered those who wandered; it was an assertion of their belonging and ownership of the public spaces in our cities, equal to those of us who own property and make comfortable livings. I keep coming back to his work as I see the rest, as it seems to lay the foundation for interpreting the functionality of the rest of the pieces in the exhibition, and establishes a firm historical context for its discussion. Another one of Wodiczko’s video pieces, “Veteran Vehicle Project,” sees an adapted military humvee replace its gun turret with a projector displaying the confessions of a soldier who feels left behind by the country he fought for. His words are projectiles, like bullets, ricocheting off the side of the building–not nearly as deadly, but just as unnerving.

Architectural foci and faux family portraits

Jessica Vaughn and Andrew Moore both use the medium of color photography to highlight disparities in cultural identity within the city. Moore photographed the faded glory of an industrial megastructure, Michigan Central Station in Detroit–the physical disintegration of the promised permanence of industry. In its shadow lies a gutted and shattered house that is currently used as a creative space named Imagination Station. I could fathom the factory whispering to the house, imparting a comfort even in the structures’ new lives: “Don’t worry, I’m still here, and it will all be okay.” Moore seeks to humanize the depiction of Detroit amid a slew of reportage that dismisses the town as down-and-out.

Vaughn worked in West Philadelphia, incorporating sculpture and performance into her imagery, and using the colors of the Pan-African flag and the Rainbow Push Coalition to “activate” buildings relating to black working-class aspirations. After I read the catalog, her work came into focus, but without context, I must admit it is aesthetically flat, and I wonder whether the photograph was the most appropriate way for her final idea to be displayed. Perhaps the original colored objects with which she concealed herself would have spoken for themselves in the gallery.

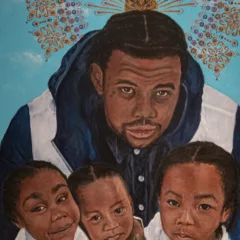

From here I walk to Addams Hall, a much more brightly lit space. The work here is also much more immediately inviting, and generally more tongue-in-cheek. Jamie Diamond’s artificially constructed family portraits are almost nauseating in their complacency, yet maddeningly contradictory when her method is revealed. Diamond used Craigslist (the printed-out versions of her ads are displayed here as well) to gather strangers to form fake families and arrange them in fancy hotel rooms for idyllic portraits.

The hotel environment is meant to be uniformly comforting and familial, yet completely indifferent to differentiating features of domestic values and iconography. Another work of Diamond’s, “Living Family Portrait,” is a video of another artificially assembled family stuck in smiling-picture-pose in a public park. A hidden camera catches the their creepily enduring, plastic smiles. The indifference of the public is highlighted when a woman sits down on the bench in from of the camera, lights up a cigarette, and gives not even a second thought to the scene in front of her.

Confronting prejudice, tradition, and fantasy

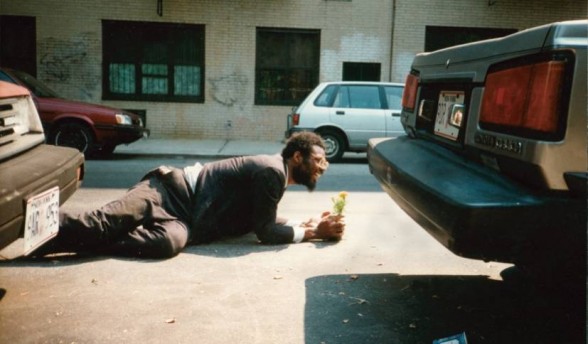

The most confrontational piece here is William Pope L.’s “How Much is that Nigger in the Window a.k.a. Tompkins Square Crawl”. The video shows a man’s struggle to crawl through New York’s East Village, carrying a small potted plant. The artist painstakingly asserts blackness as “a lack worth having,” lowering himself to the ground as a gesture of fortitude and solidarity with those living on the street and the lack of regard for their condition by not only the public, but city officials as well. His is a struggle that sticks with you–a sense of disgust with the status quo grows stronger with each passerby who fails to stop and see if the crawling man needs assistance. Is this really the best we can do for our fellow man?

Two artists working within a familial narrative held up the last section of Addams’ space. Paul Salveson’s “Master Sauce” plays off of the Chinese tradition of a “master stock,” saving part of every recipe for use in the next and therefore establishing a generational continuum of flavor. The photographic series is his exploration of material inheritance and how the things that we can touch, taste, and smell establish tradition in the home.

Thai videographer Apichatpong Weerasethakul contributes his film “Haunted Houses,” an adaptation of a popular soap opera in which the roles are acted by non-professional rural townspeople. The acting is expectedly abhorrent, but that’s nowhere near the point–the collective fantasies embodied by television personalities are exposed as absurd and archetypal, out of touch with the legitimate human condition and yet still harbingers of hope. Lengthy shots of family portraits in the actors’ homes are eerie and poignant, convalescing in their own way alongside the trials of their kin.

The Addams Gallery portion of the show closed on Nov. 22, while the Slought Foundation space will be on view until Dec. 20, 2014.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art.