[Andrea appreciates an intimate retrospective of Nam June Paik’s forward-thinking work, in which the artist’s foresight and sense of humor are easily apparent. — the Artblog editors]

Go, go, GO to the Asia Society before Jan. 4, 2015 to see Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot–even if you’ve seen lots of the artist’s work before. And if you’ve only seen the work in photographs, you’ve seen nothing. I thought I had a good understanding of Paik’s output; I’d been to the big Guggenheim retrospective in 2000, had read much published material, and briefly worked with the artist in connection with a project for Miami International airport, and with his dealer, Carl Solway, in organizing an exhibition of his robot portraits. I was still delighted, amazed and informed by the current exhibition–so much so that I intend to return.

Connecting with technology’s personal side

Paik’s late work can be presented as spectacle, and his huge, multiple-monitor pieces are spectacular–but they do not sum up the artist’s concerns. He was always interested in people, and the possibilities new technology offered us to know ourselves and communicate with others. During a time when C. P. Snow’s divide between science and the humanities appears unbridgeable, Paik reminds us that science and its tools are man-made, and under human control. He considered it the artist’s place to explore such ideas.

A global artist before the concept existed, the Korean-born Paik studied philosophy and music in Japan and Germany, and conducted his artistic career entirely from New York City. This placed him within the early activities of Fluxus–the artistic circle around John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Happenings and performance art, and the beginnings of video art–but he transcended all categories.

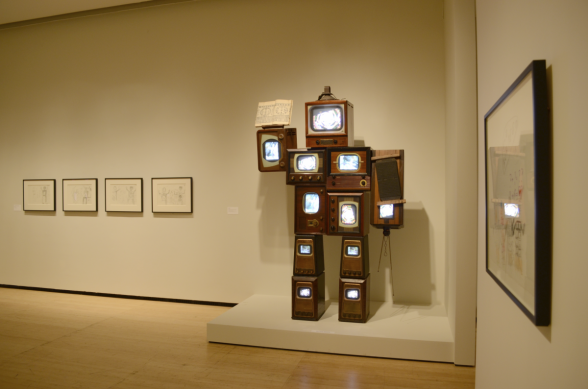

The exhibition opens with the charmingly homemade-looking “Robot K-456” (1964), named for Mozart’s late piano concerto; Paik undoubtedly loved its sequential numbers, as he was sensitive to words and nomenclature, and liked jokes involving language. It epitomizes the artist’s perspective: the precariously-wired-together assemblage of parts from the hardware store was a bi-sexual humanoid, although its male organ disappeared long ago. It walked, talked, and defecated small beans. Its functions were entirely controlled by the remotes in the artist’s hands, and “456” was not about to take over the world.

Premonitions of the role of television

“Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” Paik’s 1984, simultaneous, live television broadcast is shown in its 38-minute entirety, as a video on the second floor of the exhibition; it involved participants in both New York and Paris, and was transmitted to France, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands, and the U.S.. The cast of major artists he assembled, including Laurie Anderson, John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, Philip Glass, and Joseph Beuys, is an indication of the broad, artistic circles in which he lived and worked, and his interest in collaboration. “Our Orwellian celebration is not quite Orwellian,” Paik said. “Whereas TV for him [Orwell] was an omnipotent means of suppression (needless to say, it is so subconsciously now, everywhere in the world), we would treat this tool neutrally and try to inject a better Vitamin into it.”

Rarely-seen creations and collaborations

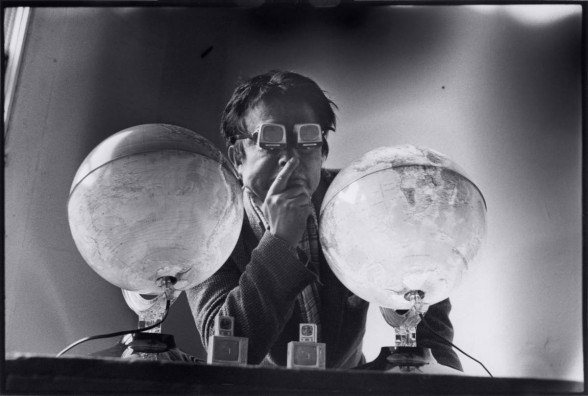

The exhibition includes documents, sketches, and proposals, such as the “Utopian Laser TV Station” (1966); videotapes, including “Electronic Opera #1” (1969); numerous rarely-seen drawings, and substantial video sculptures. It demonstrates the possibilities of the synthesizer that the artist developed with engineer Shuya Abe in 1969, which enabled manipulation of video images to create kaleidoscopic collages, decades ahead of the broad availability of video-manipulating software. There are also artworks that featured his many collaborations with cellist Charlotte Moorman, such as “Light Bikini” for “Opera Sextronique”(1966/75); the cellist was arrested for indecency at its debut performance.

Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot is the right size, rather than the swollen presentations we have come to expect from monographic exhibitions of important artists. It conveys the range of Paik’s thinking, but is intimate enough to allow visitors to actually spend time with the time-based work. It also demonstrates something of the artist’s sense of humor; Paik loved to laugh, and never thought serious ideas precluded humor. The exhibition also reveals just how much we are living in a future that Nam June Paik long anticipated–one that includes digital television, portable electronic devices, the domestic use of computers, the internet, Google Glass, Facebook, Skype, online education, and a range of other networked activities.

The exhibition catalog, edited by Melissa Chiu and Michelle Yun (Yale University Press), ISBN 978-0-300-20921-1, does not contain important, new scholarship, but is a good introduction to the artist’s work, and is particularly valuable for reproducing a number of the artist’s typescript notes and letters. No one is better on Paik than Paik. The catalog is attractively illustrated, contains appreciations by several younger artists, and a selected bibliography.

Nam June Paik: Becoming Robot is on view at the Asia Society, 725 Park Ave., New York, NY, until Jan. 5, 2014.