[Kitty finds truth and poignancy in a show revealing the lives of Philly residents past and present. — the Artblog editors]

Jeffrey Stockbridge thinks he’s a photographer.

He very well may be, judging from his accolades here and in Europe since his B.S. in photography from Drexel University in 2005.

But his true calling is as a cultural anthropologist, who uses his camera to document the detritus of society today and his heart to collect mementos left behind.

Raw details

Consider “Willie and Rose,” a large-format color photograph. Stockbridge captures Willie with a cigarette in hand sitting on the stoop of his West Philadelphia home with Rose looking out the storm door behind him. Their two-story home, with crinkled plastic lining upstairs windows to keep out the cold, sits next to an abandoned red house with trash-strewn lots and falling fences on either side. All around them is abandoned. They are the holdouts: too poor to give up their only asset in a bleak neighborhood.

InLiquid, an online arts organization, is sponsoring the Jeffrey Stockbridge exhibit, called Homegoing: Photographs from 2004-2008 through Jan. 16 at the Painted Bride, on Vine Street near 3rd. The show is part of InLiquid’s Art For Action program, which uses art exhibitions of its members as a way to engage in community dialogue about subjects of interest in the area.

Stockbridge, who befriends the people he photographs, is exhibiting “Willie and Rose” and eight other framed works. Only four are large-format archival inkjet photographs he took between 2004 and 2008. They are poignant photos of lives, or the remains of lives, once lived on the edge.

Equal billing is given to his found objects: three heartbreaking penciled letters and two photographs, reprinted as sepia lithographs.

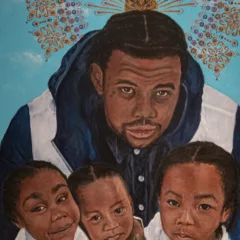

“J.B.” is Stockbridge’s exquisitely detailed portrait of a 30ish African-American man, with a slice of light glancing off his face, his lit cigarette by his side, standing in the black shadow of a doorway of a painted red brick house. He wears a black watch cap, an inside-out jacket from Archbishop Wood High School and jeans by the front door, which looks like you could pick up a splinter if you touched it.

In “43rd and Haverford, No. 1,” the photographer’s focus is on a dresser in a bedroom, with disheveled clothing, once in a torn blue flowered cardboard box but now heaped on the floor and on the metal-pipe double bed with a frayed coverlet. The mirror of the dresser reflects the dusty record player with its arm ready to drop on the vinyl record. A white mug sits on a shelf of the closet. The transparent curtains allow light to fall on the abandoned room, with plaster from the cracked ceiling.

Who stayed here and why did they leave so quickly? Stockbridge’s photos and found objects show a distinct way of life, but raise more questions than they answer.

Whispers from the past

Another large-format photo, “43rd and Haverford, No. 2”, shows a dried bouquet of flowers on a dusty step of a pie-shaped brown stairwell. Gold paint is peeling from the walls and grit is dispersed on the floor in what must be an abandoned house. Who lived there and what were they celebrating?

Of his two found photos, one features a sassy babe in a pompadour wearing a sequined black dress with gold leaves and high heels, with one hand on her hip and the other holding up high a white fur shawl longer than she is tall. The other photo could be an off-duty church lady, wearing a pageboy hairstyle with a demure smile in a plain blouse and skirt.

The three framed letters describe the struggles of three female authors. A Dec. 20, 1989 unsigned letter is addressed to James: “If I don’t bring home money you get upset with me like tonight. . . James you are treating me like I am your whore. James I love you . . .”

An undated letter on looseleaf is written to Mama: “I want you to come live with me.” The unnamed author then appeals to her mother for money for a house that she and Cal want to buy, which only costs $13,050. She needs $800 “by next Tuesday.“

The third letter is a song to the Lord: “I am happy tonight.”