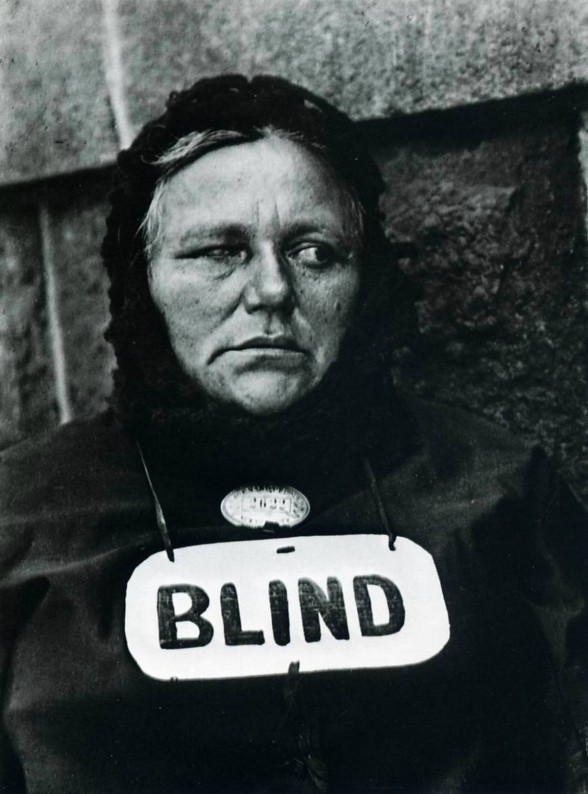

[New Artblog contributor Diana takes a close look at one of Paul Strand’s seminal photos, considering the photographer’s role in the dehumanization of his street-portrait subjects. — the Artblog editors]

If it weren’t for the hint of the half-closed eye and the shout of the sign emblazoned on her breast, you’d hardly get it. Her eyes dart to the left, as if her peripheral vision has picked up movement. For a second, you wonder what she’s looking at, then realize that your experience of trompe l’oeil is only one of the many ironies this iconic photograph poses.

The question of complicity

From a semiotic point of view, the sign reads like a label that reduces her identity to the visual perception of those who have the power to observe her. In this sense, the sign is as much an accusation as a proclamation, suggesting that the voyeur who “sees” her is blind to her humanity. Compounding the dehumanizing effect is the peddler’s badge, which diminishes her dignity as well as her identity, since peddling was all too often a euphemism for begging. She is not an individual, but a member of a marginalized, stigmatized, ostracized group, as if she were Jew in Nazi Germany with a gold star on her sleeve.

Though Strand was captivated by her “absolutely unforgettable and noble face,” the question is whether he, through the act of taking the photograph and the manner in which he took it, is complicit in the dehumanization. This photograph is one of a series of portraits Strand shot of the poor, the old and infirm, and the working class in New York during the early 1900s, with the intent of promoting social reform. To preserve their anonymity and the candor of the shot, Strand used a fake camera lens to get close to his subjects without their knowing he was taking their picture. But one cannot help but wonder to what extent this subterfuge had an alienating effect on him. The idea of the photographer using a blinder to shoot a blind person is in itself disturbing. It skirts the border between documentation and exploitation by treating the subject as “the other” in the most extreme sense–an object, an anomaly, even a freak.

Noting the monumental quality of these early street portraits, Peter Barbarie, curator of the Strand exhibition, suggests that Strand himself was perhaps “unsettled” by them, given the fact that he made no others for 16 years. One can only speculate whether this portrait in particular, in which the subject is pilloried by a number and word, did not give him pause.

This photograph is on view in the exhibition, Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through Jan. 4, 2015. The exhibition consists of 250 prints, screenings of films, works by fellow artists, and archival materials.

Diana Loercher Pazicky is a writer in the Philadelphia area. A former art critic for the Christian Science Monitor and English professor at Temple University, she currently writes poetry and is working on a full-length play.