[Diana zeroes in on the dialogue between two works at the PMA’s survey of its African-American collection, remarking on the messages implicit in each piece. — the Artblog editors]

Most of the works of art in the exhibition Represent: 200 Years of African American Art, now on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, are explicit depictions of the African-American experience. Even when they infuse Realism with abstract elements, they are recognizable representations of scenes, figures, and objects, and more importantly of an attitude or perspective on that experience.

Irony, rage, and rebellion

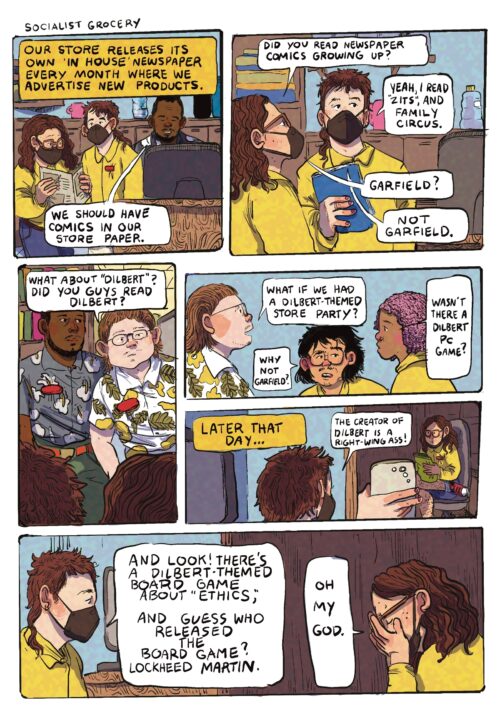

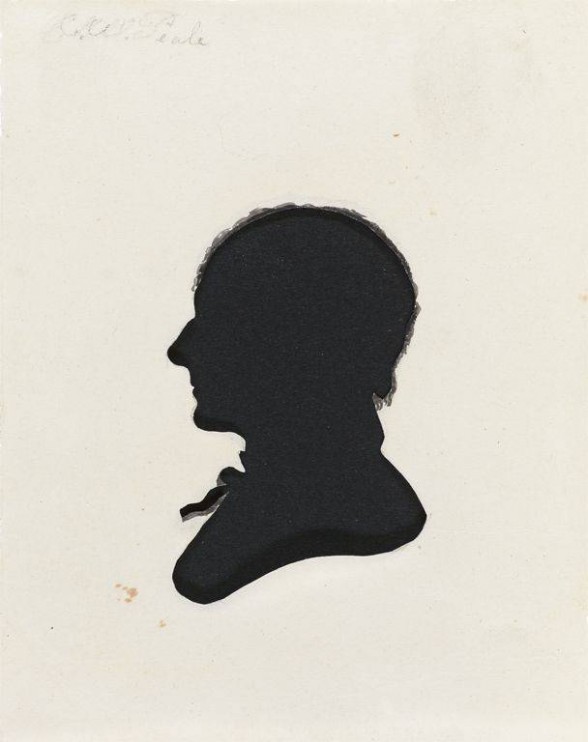

A tantalizing exception is the earliest work in the show, “Peale Family Silhouettes”. Attributed to Moses Williams, a former slave, these black silhouettes mounted on white paper represent the family of Charles Wilson Peale, a Philadelphia artist, naturalist, and pioneer of the museum. Williams was Peale’s slave from childhood to age 28, during which time Peale trained him in silhouette-cutting and taxidermy. After Williams gained his freedom in 1802, he plied his trade, capturing the profiles of the Peales, other wealthy white Philadelphians, and visitors to the Peale Museum, using a device Peale developed called the physiognotrace.

The visual irony is inescapable–his former white masters and mistresses et al in blackface. One can only speculate how Williams reacted: smug satisfaction at accomplishing racial inversion, bitter reflections on immortalizing his oppressors, forlorn sighs on submitting to economic exigency. We don’t know–and never will–what went on in his mind. Perhaps the irony did not even occur to him. But the implicit irony exerts a stronger gravitational pull on the current viewer’s imagination than an explicit answer ever could.

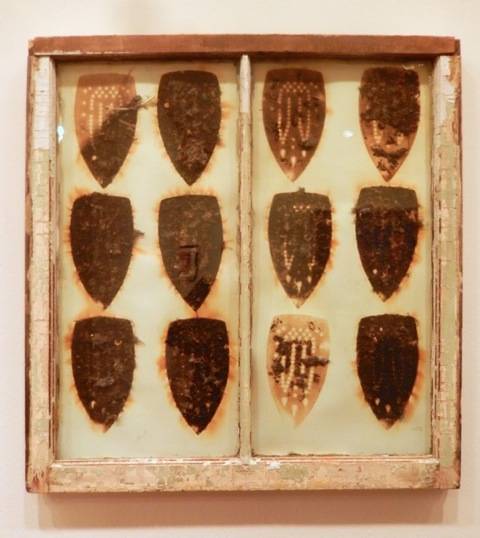

In another room, Willie Cole’s “Reversed Evidence” (1992) ingeniously reverses the use of a commonplace household object, the iron, to encode a political message. In so doing, Cole’s mixed-media work creates an inadvertent dialogue with Williams’ silhouettes, expressing with a very different gallery of faces the pain and injustice that the silhouettes mask. Two sheets of cream paper mounted in a painted window frame display deep scorch marks from an iron, some on pasted padding that represents lint from laundry or even clothing. Clearly the intention is to commemorate the labor of African-American domestic servants who toiled in the households of their white owners.

But the marks also suggest rebellion and destruction, stemming from an underlying fury that could burst into flame. The structure of the iron face evokes not only African masks but actual faces, some with eyes, as they stare through the windows of a house in which they are trapped inside. These “portraits” conjure up the memory of the countless anonymous African-American women who wasted their lives in subjugation and service to others. (Note: Tillie Olson’s celebrated short story, “I Stand Here Ironing” (1961) provides an excellent complement to Cole’s visual statement.)

Whatever outrage Williams might have felt has been made visible in analogous form by Cole, who rectifies the past by using the language of symbolic images to speak for his ancestors, those who could not speak for themselves. The unexpected synchronicity of these two works alone warrants a visit to this major survey of a tradition in American art too long neglected.

Represent: 200 Years of African American Art is on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through April 5, 2015.