Bayside Revisited is Gabriel Martinez’s elegy, and perhaps also his eulogy, to a rare place and to a community where gay men were free openly to express their sexuality in the early 1980s. The exhibition is a celebration of that place and that freedom, tragically punctuated by the devastating epidemic of AIDS, which killed thousands of gay men in the decade that followed and derailed an emancipating sexual revolution that had flourished with promise in the 1970s.

The magic of Fire Island

It should not be forgotten that in 1980, there were very few places in the country, or in the world, where gay men were free to express their sexuality. Indeed, in 1980 and continuing through the ’80s, some 25 of our states still criminalized consensual sexual relations between gay adults, and in 1986 the United States Supreme Court infamously declared that those laws did not violate the Constitution. Much did change in the next 30 years, but far too much has remained the same.

To appreciate Bayside Revisited, you need to know something about Fire Island. Fire Island is a barrier beach that runs parallel to the south coast of Long Island, beginning just east of Jones Beach, about 60 miles from New York City. The island, which sits some 4 miles across the Great South Bay from Long Island, is 30 miles long and two blocks wide. Across those two blocks is the Atlantic Ocean. Indeed, from most spots on Fire Island, you can see both the ocean and the bay.

Dotted along Fire Island’s 30 miles, you find a series of small, autonomous, summer communities. I have spent many summers in one, Seaview, which is near the center of the island. A few miles to the east of Seaview, you find Cherry Grove (pictured above) and next to it the Pines, which you may have heard of: both have long been famous havens for gay men (and a fair number of lesbians as well). In 1966, the wonderful writer, poet, and art critic Frank O’Hara, a gay man, was killed by a jeep on the beach in Fire Island. In 1971, an iconic hardcore pornographic film featuring gay men, “Boys in the Sand,” was shot in Cherry Grove. The film starred Casey Donovan and was directed by Wakefield Poole. Its original title was “Bayside”.

Visiting Fire Island is a magical experience. Essentially just a spit of sand, the island is a diaphragm that shields Long Island from the wrath of the ocean. During Hurricane Sandy, as in many other storms, the ocean breached the island and met the bay, washing away many homes and much of everything else in its path.

The island itself is a mix of beach, scrubby small trees and bushes, seagrass, dunes, sky, and water–a paradise for birds–and in each community, there is an assortment of homes. There is very little commercial activity on the island, and most amazingly, there are no cars. There are bridges that reach the two ends of the island and terminate in parking lots, but that is as far as cars are able to travel. To get to the any of the communities on the island, you have to take a ferry from Long Island–the Mainland–and then you walk to your destination, pulling your luggage in a wagon. In some places, you can use bicycles. There are emergency vehicles on the island, but for the most part it is a world without cars, and with cars removed from your consciousness, you feel like you are a million miles away from civilization. When I was a child and school ended in the spring, our family would head for the island, and when we got off the ferry we would take our sneakers off and not put them on again until the end of summer.

If you had visited Cherry Grove and the Pines in the summer of 1980, you would have found yourself in communities of gay men. You would have found the Belvedere Guest House for Men and the Grove Hotel. You would have found a disco bar. You would have found a beach full of nude men. The atmosphere was hedonistic: it was filled with joy and liberation. And sitting between Cherry Grove and the Pines, you would have found a scrubland called the Meat Rack, running from the bay toward the ocean, where gay men would hook up with each other.

Resurrecting ghosts

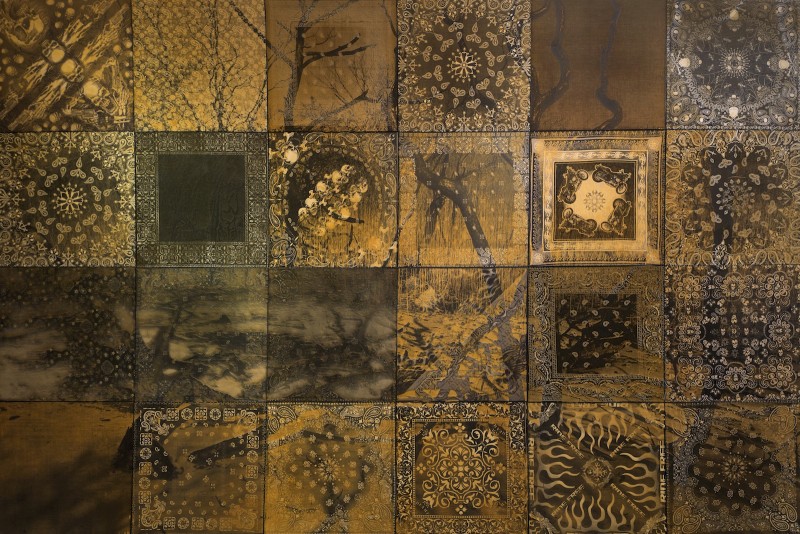

Bayside Revisited includes a slideshow of starkly illuminated, harsh, seductive nighttime images of the Meat Rack that Martinez photographed last winter. A path weaves though an oasis of small, barren trees that remind us of human figures, monuments to the men who cruised the area in 1980, many of whom fell victim to AIDS. One of Martinez’s pieces, “Live Hard,” is a chilling patchwork (reminiscent of the AIDS Memorial Quilt) of a variety of handkerchiefs that were hung out of the back pockets of those men to signal information about their sexual proclivities (the “hanky code”), superimposed upon an etching of the wooded landscape of the Meat Rack.

Bayside Revisited also features an installation in which 16mm clips from “Boys in the Sand” are projected on a disco ball and then reflected onto a Print Center gallery wall that Martinez has plastered with sand from the Meat Rack and the beach (with some glitter added in), with the soundtrack of the film playing in the background. The visual effect of the installation, like home movies shot in the pre-digital age, is almost nostalgic: I want to call it disco-nostalgic.

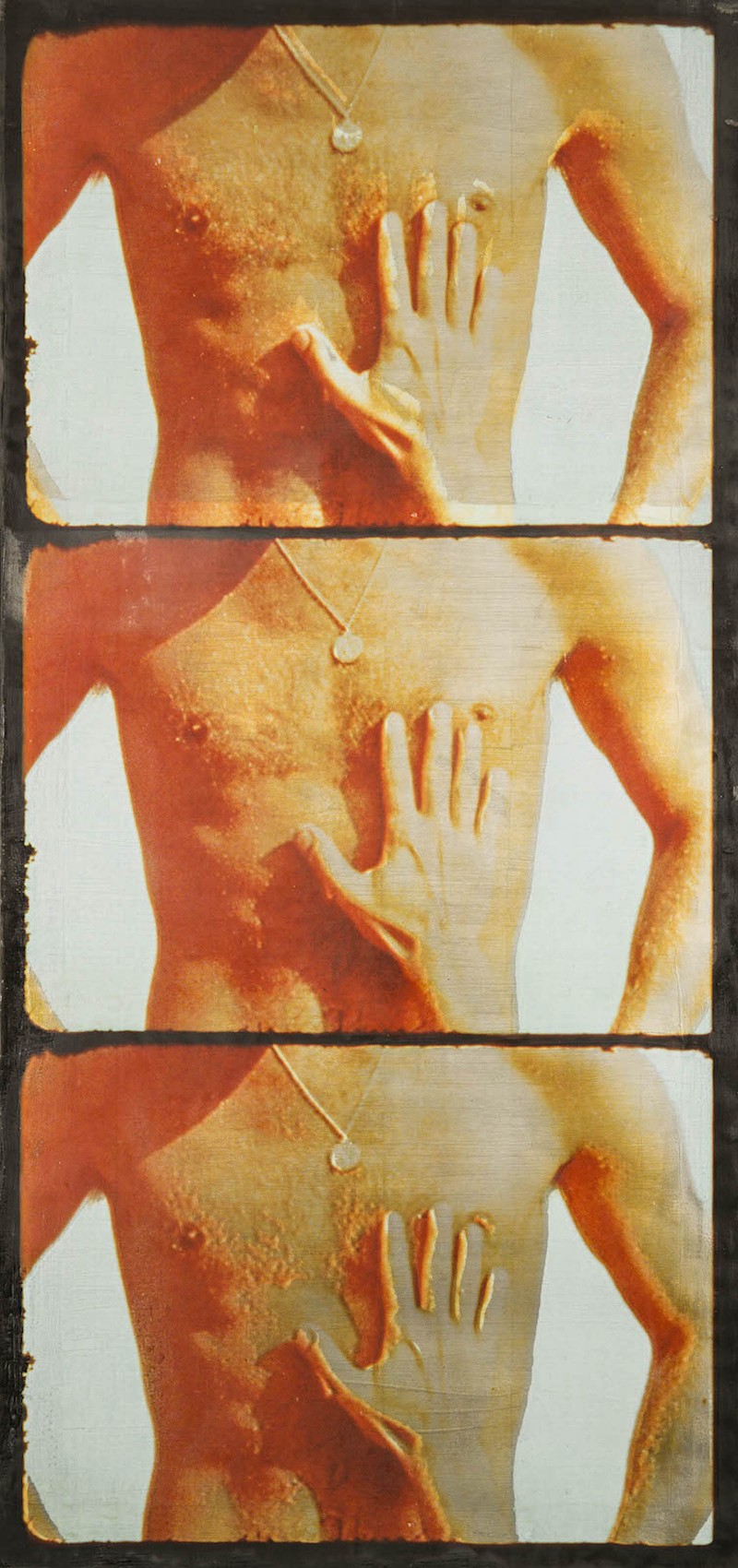

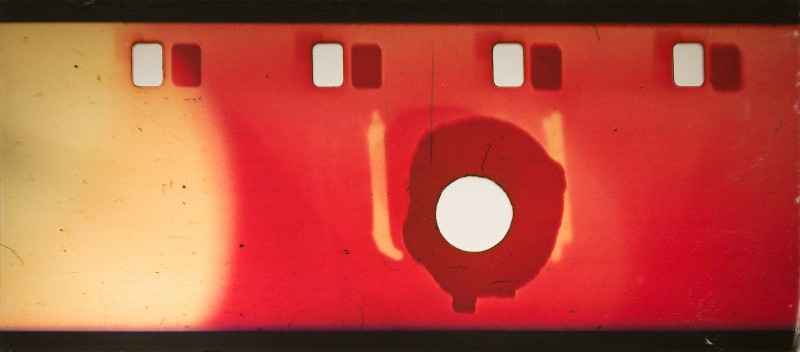

Martinez has also taken stills from the film, digitized them and printed them upon palladium leaf and other media. “BITS (Bayside 5),” the vertical, suggestive triptych pictured below, evokes something about both the pride and the anonymity that one might have experienced in the Meat Rack in its heyday. With “BITS (Filmstrip 1),” below the triptych, Martinez displays his glorious sense of color and composition in an abstract work created from a section of damaged 16mm film, which invokes the symbol of a portal into the world he is exploring.

Empty environs

Among the other works in the show are two beautiful screen prints of photographs taken by Martinez in January 2014, shot from the Meat Rack and looking toward and over the bay. One of them, “Bayside (5),” featured at the beginning of this review, presents a breathtaking and unusual panorama of the frozen bay that looks almost like an aerial shot. Martinez described to me the scene at the Meat Rack when he arrived there: “What I discovered was isolation, frigid and solemn, yet powerfully charged. I wanted these images to present the antithesis of the festive social scene that was/is Fire Island. I created silver leaf hybrid prints that create a sense of decay, nostalgia, and trauma.” Certainly one thing Martinez captures in “Bayside (5)” is the grandeur of that environment when stripped of human festivity, folly, and tragedy.

Martinez’s methods

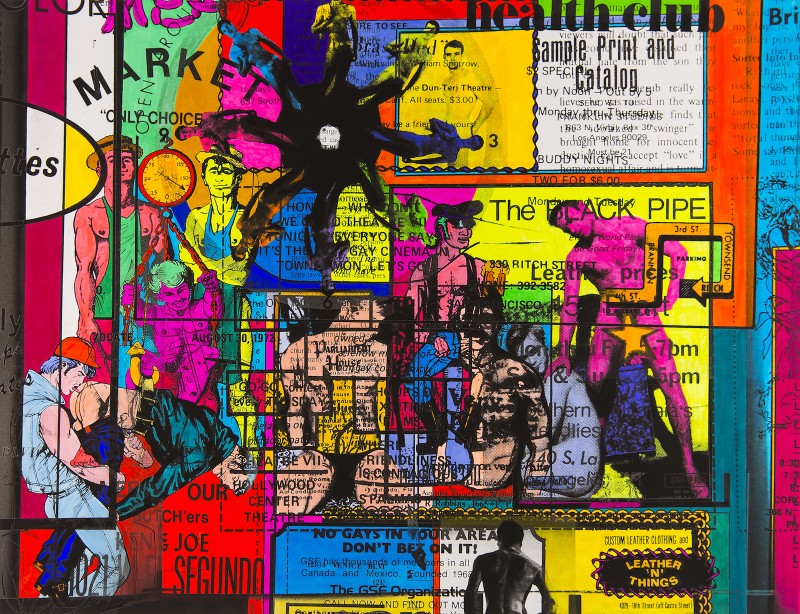

There is also a disturbing photograph in the exhibition of the ruins of the Grove Hotel, which burned down last year. Martinez, utilizing a gel flash, captures the scarlet essence of the fire and at the same time suggests the red dark rooms of gay leather clubs. Finally, Martinez presents four masterfully assembled digital collages of vivid color images he has compiled from various queer publications. Note the text at the bottom of “The Black Pipe,” pictured below, which reads: “No gays in your area? Don’t bet on it.”

I had the privilege of previewing Bayside Revisited with Gabe Martinez and the photographer Stephen Perloff, who is the editor of The Photo Review. I hope that Mr. Perloff will discuss Martinez’s impressive technical wizardry, which the exhibition demonstrates, and which in various ways harkens back to the era Martinez is trying to invoke in the exhibition. Although I am not competent to do so, I can speak to the results: the work is awe-inspiring, thought-provoking. It is at once a celebration and a wake. Martinez has a gift for composition that is reflected in all of this work, as well as in the curation of this remarkably emotional exhibition.

Gabriel Martinez, a Cuban-American, is a Senior Lecturer in Photography at the University of Pennsylvania. He received an MFA from Temple’s Tyler School of Art and attended Skowhegan School of Sculpture and Painting. Martinez is represented by Sams∅n Gallery, Boston, and his photography, performance and installation works have appeared in numerous venues. Bayside Revisited is part of The Print Center’s celebration of its 100th anniversary, and has been artfully curated by the center’s John Caperton together with Martinez. The exhibition will be on display in The Print Center’s lovely space through December 19, 2015. Don’t miss it.