At the turn of the millennium, the Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, under the label Arteast 2000+, began to systematically collect art of the former Soviet bloc and the Balkans from the 1960s onward. It is the most important museum collection of post-war avant-garde art from Eastern Europe, and the collection is what drew me to Ljubljana this summer.

A rich underground scene not well known in the West

Eastern European artists whose work is known in the West—among them Marina Abramović, Miroslav Balka, Sanja Ivecović, Ilya Kabakov, and Dan Perjovschi—are diverse and extremely interesting, and passing time reveals further significant artists whose reputations have been obscured by the politics of the Cold War. There were many art scenes throughout the East, often underground. While the artists are now able to exhibit openly, they do so largely through independent, artist-run organizations, as there is still little institutional or market support. Much of the artwork was, and continues to be, produced by collectives, among them Domestic Research Society (see image below), IRWIN and NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst, New Slovenian State–both discussed below).

The Arteast 2000+ collection is an attempt to document these artists and insert them into international consciousness on their own terms, rather than waiting for the West to acknowledge them. I saw a broad selection of the collection this summer at the Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana’s contemporary outpost, the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (MSUM), part of a new museum complex in repurposed buildings of former military barracks. Russian avant-garde art of the period has been presented widely in the West, but the most complete U.S. view of this period in Eastern Europe was the exhibition, Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s, organized by the Queens Museum of Art in 1999 (catalog ISBN 0-960-451498-0). The Museum of Modern Art, New York is catching up with an exhibition which just opened of 1960-1980s art from Eastern Europe and Latin America.

Artists from marginalized Eastern European countries: political and not provincial

Seeing the work and talking with a couple of younger members of the art scene in Ljubljana, I was reminded of a comment Nam June Paik made when situating himself as a Korean: Artists from poor countries cannot afford to be boring. My visit demonstrated that artists from marginalized countries cannot afford to be provincial; the Eastern Europeans weren’t. They were and are hungry for contact with the rest of the world. They clearly read all they could get their hands on, and now make active use of the resources of the Web. Their politicized art put its makers at real risk and interacted with actual politics. Recently-produced works and my conversations revealed sophisticated understanding of art, criticism, and theory coming from the mainstream, Western art establishment, and a broader view than I’ve often found at home.

The Arteast 2000+ Collection: focus on conceptual, performance, video, photo and installation

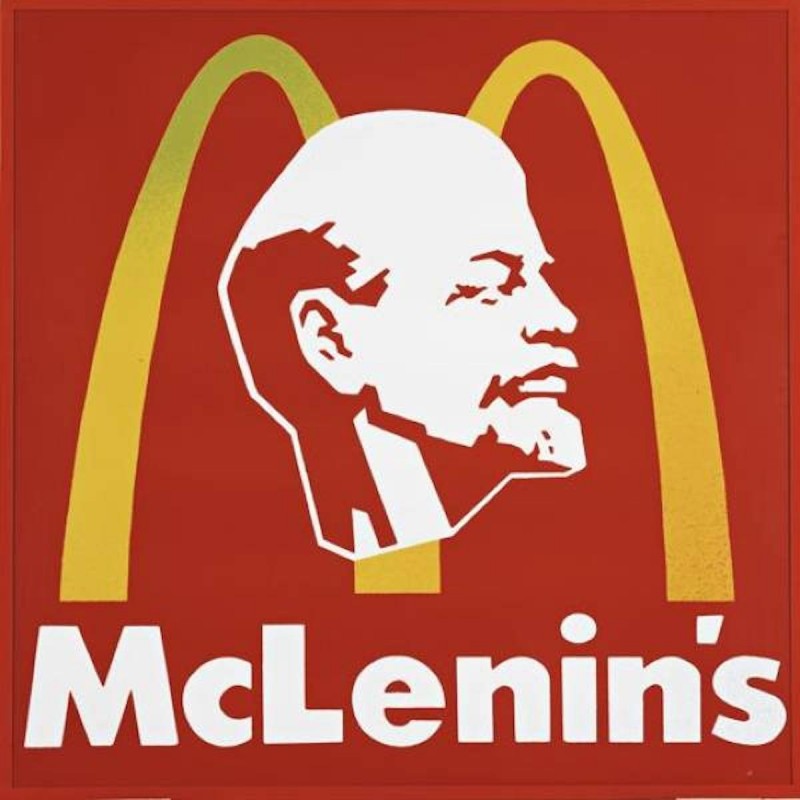

The Arteast 2000+ collection contains a good deal of conceptual and performance-based work—much of the later documented in the catalog to a 1998 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art Ljubljana, The Body and the East, ISBN 0-262-52264-0, printed in English and distributed by MIT Press—as well as video, photography and installations. Most of it makes direct reference to the social and political situation of the time. While work done pre-1989 opposed the repressive states, much of the work created after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the break up of Yugoslavia has turned its criticism on the general population, seduced into bourgeois complacency by consumer culture. Recent work also addresses the newly-organized states with their narrow definitions of nationalism in a region of perennially shifting boundaries and a history of cultural mixes. The artists are cosmopolitan by choice; they resist being constrained by the fictions of newly-established nationalism and are aware of the carnage wrought in its name.

Totalitarian design motifs critique the current state

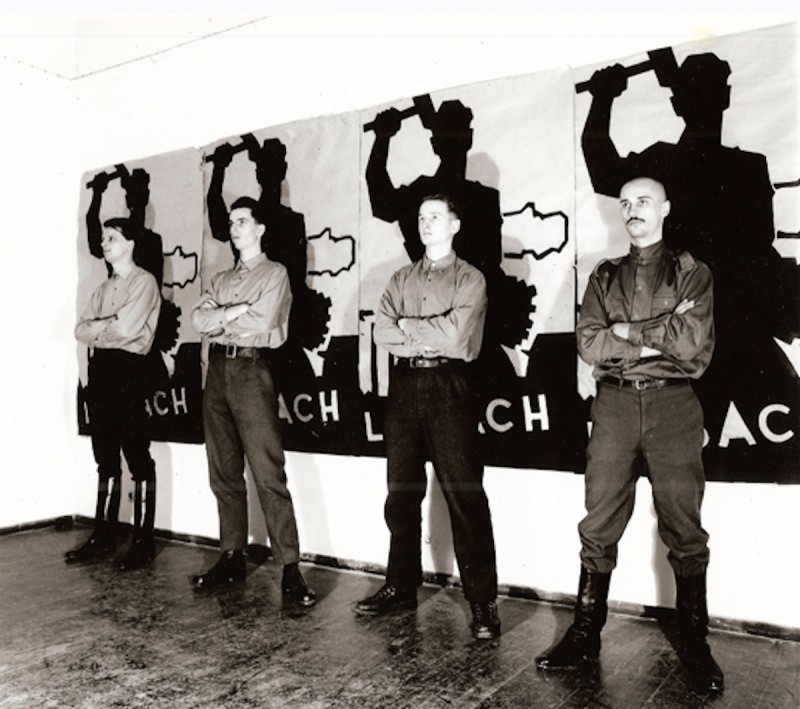

I saw three further exhibitions of recent work at other sites. The Museum of Modern Art was showing the fascinating exhibition, dense with both video and text: NSK from “Kapital” to Capital: Neue Slowenische Kunst—The Event of the Final Decade of Yugoslavia. It documented three collectives: the musical and multimedia group Laibach, Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre (SNST), and IRWIN, from the visual arts. The three coalesced in 1984 as Neue Slowenische Kunst (New Slovenian Art), which assumed the format of an alternative state, complete with logo, flag, coat of arms, and various ministries, including a design department and a Department of Pure and Applied Philosophy. NSK combined the authoritarian languages of fascism, socialism, and nationalism under the doctrine of “retro,” which assumed variant names by each of the three original collectives. According to the curator, Zdenka Badovinac, “Rather than employing the standard forms of artistic critique or irony, NSK based its approach on subversive affirmation and over-identification, assuming, among other things, the types of society the group envisioned after the collapse of socialism.” Appearing in the trappings of totalitarianism was both more damning and less overtly objectionable than direct criticism of the state.

Art and life collide in NSK faux passports

With the breakup of Yugoslavia and the formation of multiple new states including Slovenia, which had never been independent, in 1992 NSK transitioned into NSK State in Time. It began to establish international embassies and consulates and issued passports. Anyone can apply for an NSK passport on the NSK website www.passport.nsk.si for a fee of 24 Euros. NSK State in Time is a territory-less entity, a state of mind. NSK and NSK State in Time are artistic responses to very specific political situations; in 1983, Laibach was banned by the president of the Ljubljana City Commission of the Socialist Alliance of Working People of Yugoslavia. NSK State in Time has also had unintended consequences outside the region, such as the many requests for NSK passports from Nigerians who think, or hope, that they can be used to enter Europe.

While the exhibition emphasized the embeddedness of all of the work in its contemporary, political context, an outsider could sufficiently comprehend at least some of the artistic and political targets of Laibach’s neo-Nazi uniforms, use of the name given Ljubljana under both Austro-Hungarian rule and German occupation, and motifs from Malevich; IRWIN’s video of the official-looking placement of a huge, black square in Red Square, or their photographs of soldiers from various European armies posing with NSK armbands as NSK military; and SNST’s adoption of the utopian manner and visual style of Russian avant-garde theatre in “Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav” (1986) .

The exhibition has its own, comprehensive website, and the catalog of the same name has just been published, in English, by MIT Press (ISBN 9-780- 262029957).

The other exhibitions were Splice at Galerija Škuc, a space for regional and international contemporary art since 1978, and Homage to Malevich; Black Square Continued at the City Gallery of Ljubljana (Mestna Galerija Ljubljana), in the town hall. The later was one of many exhibitions across Europe organized to mark the centenary of Malevich’s “Black Square,” and focused on the response of artists from the former Yugoslavia to Malevich’s iconic image.