The Edifice, a group exhibition at Old City’s Synderman-Works Gallery through June 11, will appeal to the architects arriving in Philadelphia for this month’s American Institute of Architects Convention. From Dan Anderson’s small-scale water-tower-turned-teapot to Robert Winokur’s series of model-size American clay houses, the exhibition includes work that addresses notions of structure, function, and historic preservation.

The work of artists Scott Kip and Mary Fischer, however, drew my interest as they respectively considered how an edifice shapes our sense of perception and conveys social signs.

Constructing time

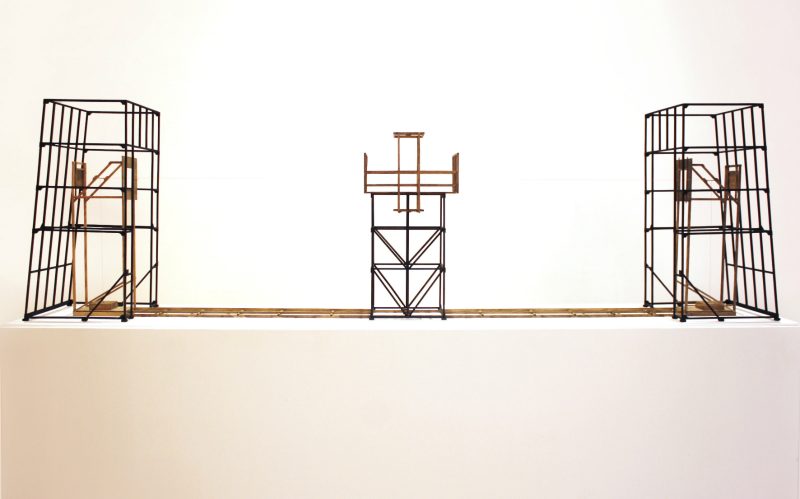

Made of model-size thin wooden beams, Kip’s “Illuminated Structures (Past, Present, and Future)” reflect steel-cage construction as they resemble the skeletal foundation of an industrial building. Three small-scale squat structures stand in a line at eye-level on a pedestal. On either end, two similar forms enclose square viewing-devices and flank a central tower. The three structures are connected by a delicate red thread that runs through the open framework at center and a track-like path along the base of the forms—a spatial metaphor, Kip noted in his artist statement, of the human experience of time.

The work piqued my curiosity as the viewing squares seemingly provide a clear line of sight across the thread. Kip purposefully obfuscated the view by placing a solid wooden square in front of the way-finding device and caused my focus to shift uneasily away from a fixed point. In this way, “Past, Present, and Future” did not satisfy my gaze and undermined the purpose I assumed the viewing device held. In thinking about a sequence of time, the work denied a sense of an expected trajectory, indicated through the brightly colored thread. I found myself trying to access another view. Unable to do so, I experienced the loss of an assumption on which I thought I could depend—a comment, perhaps, on our inability to devise an arbitrary pattern to make sense of time.

The architecture of memory

Likewise, Fischer’s construction methods rely on my architectural associations. Fischer’s clay-slab technique and surprising use of under-glaze pencil-lines suggest how form operates in relation to social meaning. In the exhibition, she included about ten small-scale structures from everyday life, such as a bar, a row home, a home on scaffolding, a long house with Chinese screens, and three water-towers. To design the pieces, she began with a paper-pattern of basic shapes and built the structures of slabs joined with slip. She glazed the structures off-white and outlined them immediately with spontaneous pencil-colored lines, which she seemingly drew directly onto the clay’s surface.

For “Untitled (Cellar Rat),” Fischer crafted an edifice with a sunken-bowed roof, grimy eaves, and wonky roof lines to indicate a dive-bar—one without windows, where patrons can find a dependable escape. A sign—“Cellar Rat”—in hand-drawn block letters appears on the narrow clearstory.

French-style doors welcome the viewer who peers into the entryway in Fischer’s “Untitled (U-Shaped House).” Fischer sometimes employs a photo-transfer process to include images in her structures, and I think she did so in “U-Shaped House,” as the door images include photographic detail. The French doors, depicted in pencil-grey, echo those found in a cottage, a familiar icon of comfort similar to those I may encounter in a European countryside or rural America.

In both, Fischer’s use of pencil indicates the idiosyncratic depiction of place and suggests that the artist’s hand translates the experience. Similar to recalling a memory, her line-work and photo-transfer process provide the essential signs of place as she interpreted the image through her pictorial or photographic perspective. Similar to Kip’s work, Fischer’s structures engage my participation but ultimately remain an oblique reference to a specific time and place.

Kip’s and Fischer’s respective works underscore a sense discomfort in the act of looking or a reliance on subjective frameworks in the process of recollection. I find their work particularly relevant as they address the relationship between routine and confusion and between observation and obscured memory within the context of architecture. From their structures, I gather that to think about edifice is not to reflect on deliberate forms of shelter and safety, but, more so, to consider how the built environment metaphorically serves as a foundation for the lived experience.