The 2016 Fringe Festival opened on September 9 with “Room 21,” a mashup of music, art, and movement set in the great hall at the Barnes Foundation, one of Philadelphia’s landmark museums whose collection was assembled by Dr. Albert Barnes during the first decades of the twentieth century. Artist and curator Lee Tusman collaborated with musician and writer Jace Clayton (also known as DJ /rupture) to explore the sounds of the collection through research in the Barnes Foundation’s rich archive. The ten musical compositions assembled by Clayton echo the diversity of the Dr. Barnes’ tastes, ranging from Classical to blues to African traditional music. For audience members, the experience of “Room 21” felt like the musical equivalent to taking in the heterogeneous groups of artworks hung on the walls of the museum, creating juxtapositions that resonate in unexpected ways and prompting reflection on the connections and tensions among different cultural and artistic traditions.

Where to begin?

Before the start of the performance, there was a general air of expectation, as though we were all not quite sure what we were going to experience that evening. Unlike a traditional concert, where each audience member has a numbered seat and there is a clear separation between artist and audience, everyone milled around together at the Barnes. Although there were some benches, most people preferred to stand, and it felt like we were at a giant party rather than a formal event. It also wasn’t clear where we should look, or where the action would begin.

Musicians of the Prometheus Ensemble, dressed in long robes decorated with black and white geometric shapes (designed by Rocio Rodríguez Salceda), stood at the back of the atrium, while at the other end by the entrance was a large stage. Although empty to begin with, the stage gradually filled with luminaries like traditional Ethiopian musician Gezachew Habtemarium, pianist Emily Manzo, banjo player Ben Lee (known as Baby Copperhead), and guitarist Arnold de Boer from the legendary Dutch post-punk band The Ex (known for their collaboration with traditional Ethiopian musicians). After brief introductory remarks from Tusman and Clayton, performer Eric Rath appeared in the upper story offices, silhouetted against frosted glass, and began to recite the maker, title, and medium of the works of art in room 21 of the museum. This repetitive, almost incantation-like text acted as a leitmotif throughout the performance, tying together the musical compositions and connecting them to objects in the collection.

The musical performance opened with a string quartet by Ravel performed by members of the Prometheus Orchestra, one of the pieces of music found in Dr. Barnes’ own record collection. As the piece wound down, musicians gradually made their way through the crowd and up to the main stage at the opposite end of the atrium. This was the most active, processional part of the whole performance, for the musicians remained in place on the stage thereafter, transforming the atrium into a more traditional concert venue. The initial sense of uncertainty and expectation with which the performance had begun settled into the more familiar sensation of being at a concert, although I kept hoping to see the musicians move around some more–if only to enjoy looking at their gorgeous robes.

Mixing musical traditions

Musically, the real standouts for me were the French Impressionist pieces by Ravel and Debussy (including a version of Debussy’s “Sunken Cathedral” played by pianist Emily Manzo on an electronic keyboard), as well as the traditional Ethiopian music of Gezachew Habtemarium. Habtemarium’s haunting vocals combined with his virtuosic playing of the single-stringed lute known as the masinqo provided some of the most transcendent musical moments of the evening.

Dr. Barnes himself listened to Ravel and Debussy, and their music speaks directly to the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century paintings on view in room 21, like Amadeo Modigliani’s beautiful but unsettling “Reclining Nude from the Back” from 1917. While the musical and visual worlds of Impressionism fit together nicely in the context of the Barnes, I felt there was some disconnect between the east African musical traditions represented by Habtemarium’s playing and the collections objects, for Dr. Barnes mainly acquired ritual masks and statues from the west African Bamana, Dan, Guro, and Baule cultures, among others.

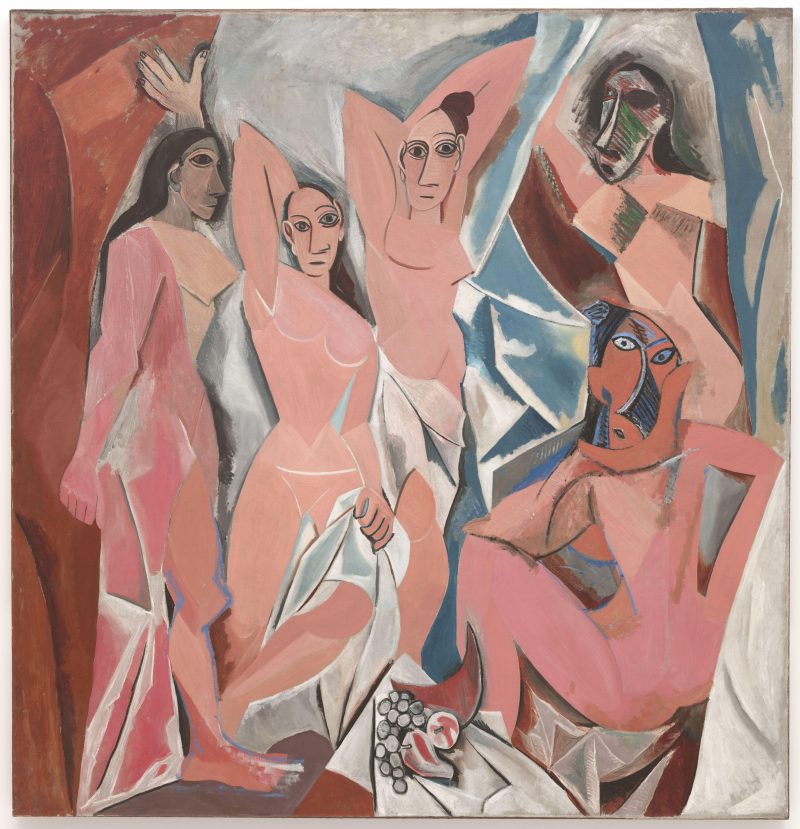

Dr. Barnes shared his enthusiasm for these west African objects with many of the European artists whose work he collected, such as Modigliani and Picasso. With her impersonal, mask-like face and overt sexuality, Modigliani’s 1917 nude harks back to Picasso’s infamous “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” First exhibited in 1916, Picasso’s painting of five Barcelona prostitutes was excoriated by critics for the fragmented flatness of the artist’s cubist style, as well as the threatening sexuality of the women–while their bodies are open and available to the viewer, their faces remain invisible behind stylized African masks. This appropriation of so-called “primitive art” on the part of early twentieth-century artists and collectors has come to be seen as highly problematic, for it reduces African art to purely formal, visual elements decontextualized from their cultural meaning and function, mere source material to be exploited and elevated by European artists. The relationship between European and African music presented in “Room 21” did not hint at this complex history of cultural appropriation, which was surprising given Clayton’s dedication to the music and culture of the global South.

Appropriately enough for a project that emerged out of archival research, there will be a digital archive of Friday’s performance of “Room 21.” Even if you were unable to attend the concert in person, you will soon be able to attend virtually through the Room 21 website. Much like researchers eager to study works in Dr. Barnes’ collection, we have to petition the cultural gate-keepers (in this case, Jace Clayton and Lee Tusman) for access to this digital archive.

For more information on Lee Tusman’s work as an artist and curator, and the genesis of “Room 21,” check out Roberta’s interview with him. Jace Clayton was also interviewed on WHYY about his new book, Uproot: Travels in 21st-Century Music and Digital Culture.