The art of the geodesic dome

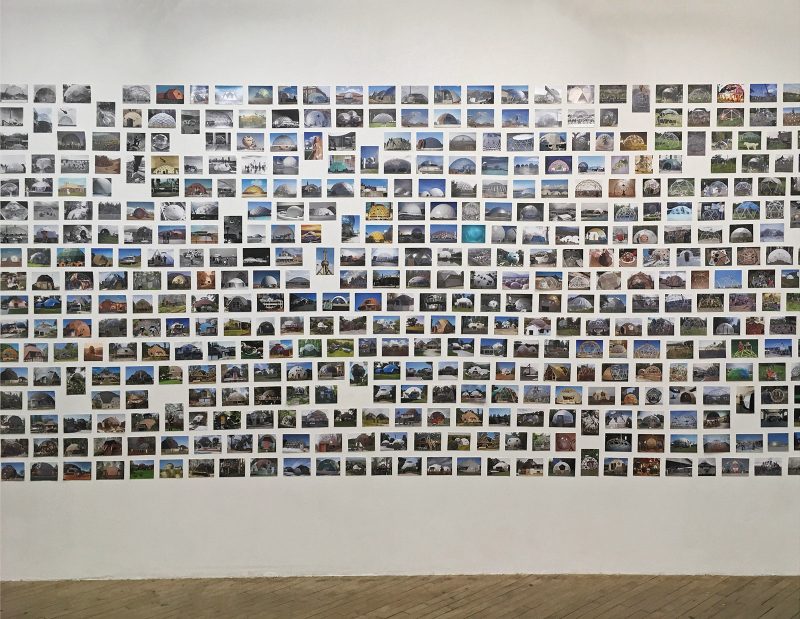

Kelsey Halliday Johnson’s unusual exhibition at Vox Populi includes two walls plastered with 4” x 6” photographs of 1,000 geodesic dome structures from around the world–shelters of many stripes, including examples from Burning Man and from the 1970s dome community in Drop City, Colorado, various iterations of glamping (glamorous camping) culture, surveillance radomes, planetariums, countless playground structures, and monumental projects such as Spaceship Earth at EPCOT and the Biosphere at Expo 67, Monteal’s World Fair (during and after the fire that destroyed it). Buckminster (“Bucky”) Fuller, a mid-20th century quasi-cult figure, popularized the geodesic dome beginning in the 1950s and designed the Biosphere at Expo 67.

Johnson’s exhibit begs a number of questions, chief among them–why did Johnson do this, and why should we care?

Trim tab, ideologies and inventions

But let’s start with this question. Why does Johnson call her exhibit Trim Tab? As I understand it, a trim tab is an engineering mechanism, such as the moveable slats that run along the rear edges of airplane wings, which have something to do with converting small steering changes into larger ones. The engineering is complicated, but apparently Bucky Fuller (who had “call me Trim Tab” inscribed on a stone next to his grave) used the metaphor to suggest that dynamic individuals (notably himself) can make small changes that stimulate larger ones that can change society in fundamental ways.

Johnson I think tries to apply the trim tab metaphor to ideas which get interpreted differently than they were initially intended, and she demonstrates this by documenting the wide variety of forms in which the design of the geodesic dome has found expression over time. The project is energized by the fact the dome architecture is utopian. It intrinsically appeals to humankind’s quest to explore and perfect.

Johnson only shot a small number of the dome exemplar pictures herself. Most of the images come from Google search results–web images, Air BnB listings, Flickr, vacation albums, Instagram, instructables, blogs, and forums. They are arranged on the gallery walls loosely by genre or use-function.

Johnson set out to document the wonder and fascination that she finds inherent in people’s reactions to geodesic designs–which range from the futuristic (including our visions of settlements on planets beyond our own) to the banal (dome-based advertisements)–and to show the different ways people photograph the same subject depending on the social use of the object. Thus, in her sample, we find impromptu functional and informational photos of geodesic chicken coops and construction photos beside images of domes that are stylized or glorified, including outdoors/camping/glamping structures.

Johnson likes to play with the way photographs are made, found, and communicated. She apparently is fascinated by retro mid-20th century futurism which, as she put it to me, “represents both our dreams and our history.” She is an artist attracted to the dreamy and to the messy. And in Trim Tab she has found an engaging vehicle through which to explore the fate of compelling concepts after they are introduced variously into a real world social environment.

The visionary, and photographic distortion

The remainder of Trim Tab includes five prints about which you may find yourself scratching your head, at least until you realize that they are an expression of the artist’s dreaminess and sense of wonder, of her preoccupation with the visionary, the unknown and the unexpected, and her interest in the phenomenology of photographic distortion, all of which relate, at least indirectly, to the ubiquitous, romantic appeal of utopian architecture. So you will find among these pieces a linear abstraction of a completely obliterated note (from the artist to herself), a surprise created by a broken Xerox machine (pictured in “Rather” above). There is a blurry, otherworldly photograph of a Tesla coil (an electrical transformer and power supply designed by Nikola Tesla, not Elon Musk, in case you were wondering). The artist saw the Tesla coil at a music festival, took the photo, set it aside and later discovered it, and presents it here with mold growing on its surface (pictured in “Rather” above). There are a pair of outer space images from NASA, blueprints including Martian blueberries, and finally, there is an image of a tourmilated quartz object (pictured in “Rather” above) that naturally forms in a kind of geodesic dome, though to me suggested a canopy of twigs.

The indomitable Buckminster Fuller

A bit of relevant history: the geodesic dome was first designed (but not named) by engineer Walther Bauersfeld in 1923 for a planetarium for the Carl Zeiss optical company in Jena, Germany. In the 1950s, Buckminster Fuller, a notorious, eccentric utopian and visionary, a philosopher, dreamer, entrepreneur, and designer, coined and popularized the term “geodesic dome,” patented the design, and made various attempts, most of which were unsuccessful, to commercialize it, primarily in the form of highly efficient shelters. Fascinated by the lightweight design of the dome, which encloses more space with less material than any other structure (“Doing more with less,” he proclaimed), Fuller envisioned shelters which could be prefabricated and delivered by air and helicopter all over the world, particularly to remote areas. He envisioned building domed cities (even floating ones) which would provide free climate control. Indeed, Bucky himself lived in a geodesic dome in Illinois (as did a number of Johnson’s relatives, pictured in the exhibit!), even though the structures were impractical in many ways and frequently leaked. Yet still today, the institute named for him–the Buckminster Fuller Institute–suggests that the geodesic dome is “the most efficient human shelter one can find,” and many commercial kits to build them are available. Something about the geodesic dome captures the imagination, and lingers.

Bucky actually lived for a time in Philadelphia in the early 1970s, where he served a number of our local universities as the “Global Fellow in Residence.” For an engaging snapshot of his colorful life and work, I recommend Elizabeth Kolbert’s profile of him which appeared in The New Yorker’s Annals of Innovation – “Dymaxion Man: The visions of Buckminster Fuller” (June 9 & 16, 2008). Kolbert ultimately quipped that Bucky “was a material determinist who believed in radical autonomy, an individualist who extolled mass production, and an environmentalist who wanted to dome over the Arctic.”

In conclusion

Something about the design of the geodesic dome captures the imagination, and the evolution of the design demonstrates how certain abstractions transmogrify when released into the consciousness of a society. Johnson’s work shows us the jump from abstraction to a series of structures which seek to embody both utopian and utilitarian ideals. Geodesic domes may be an imperfect example, but Johnson’s project does capture something of the mystery surrounding the idea-to-object process, and suggests that the results are intriguingly impossible to predict. The same of course is true of Johnson’s other subjects, including exploration in space and photographic serendipity.

Ultimately I think that the idea suggested by the trim tab, at least with respect to the geodesic dome, may be more interesting than the reality. But the concept of trim tab seems universal. It not only mimics the incremental changes central to natural selection and evolution, but anticipates worldview and paradigm shifts which are the hallmarks of revolutions in the sciences and in the arts. We are thus well served by thoughtful artists like Johnson who focus our attention upon the miracle of such phenomena.

Kelsey Halliday Johnson is an artist, writer, and curator living and working in Philadelphia. Her work has been exhibited at the Berman Museum of Art, the Delaware Art Museum, and the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center. She is the inaugural Curatorial Fellow in Photography and New Media at the Michener Art Museum. Trim Tab will be up at Vox Populi through December 18th.