The excitement was palpable among the group of 70 or so who gathered at PAFA’s Furness Building last Friday to witness Cassils’ performance, “Becoming an Image,” to be performed in PAFA’s cast hall, with life-size plaster replicas of famous antique statuary–an eerie but appropriate place for a body-focused performance by a gender-non-conforming artist.

The build-up

We underwent a series of carefully organized preliminary steps before entering the hall where Cassils would perform, completely nude, in pitch blackness punctuated only by the light of camera flashes. First, we gathered in small auditorium, where PAFA staff briefed us on the rules–no cell phones, no bathroom breaks, no coming and going, not even any movement at all once we arrived in the performance space. The darkness and stillness must be absolute, except for the strobe-light effects of the flash. All of these proscriptions and admonitions intensified my excitement, the feeling that I was about to witness something amazing and a little bit dangerous–and Cassils did not disappoint.

Ushers organized small groups and marched us into the blackness, each person holding onto the shoulder of the person in front of them–an exercise in intimacy that provided a foretaste of what was to come. As we shuffled into the cast hall, the ushers’ flashlights danced off the pale plaster bodies of the 19th century casts of sculpture from Classical Antiquity and the Renaissance that line the walls. Looming over the scene, and located directly in my line of sight was Michelangelo’s “David,” whose enormous scale dwarfed the other casts in the hall. We stood in concentric rows around the center of the space, where a large, 2,000-pound plinth of wet clay had been placed on the floor.

I talked nervously in the darkness to Roberta, who was standing next to me, and before I knew it, the room was filled with the sounds of intense physical exertion–grunting, heavy breathing, and loud smacks as the clay was struck by blow after blow. Cassils had arrived.

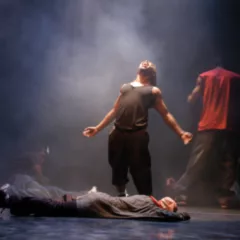

Choreographed violence

I lost track of time as Cassils (who prefers the pronoun “they”) attacked the clay in a frenzy of finely choreographed violence. A single photographer circled the performer, the brilliant strobe lights of camera flashes sporadically illuminating Cassils, a small but impressively muscular figure. The contrast between complete darkness and the bright flash created powerful afterimages. Flash–Cassils captured thrusting their knee into the clay, head thrown back, grimacing in pain–darkness returns, and the afterimage dances across my vision, tricking me into thinking they have remained in place even as I hear the artist’s heavy breathing on the other side of the room. It was profoundly disorienting, and the optical tricks made me more attentive to my other senses–the sound of Cassils moving in the darkness, the smack of flesh on clay, the cries and grunts of pain? Pleasure? Both?

A living work of art

For the first part of the performance, my attention focused exclusively on Cassils and the clay, watching it transform from a plinth into an amorphous mass. It felt intimate–the darkness, the sound of flesh, the subtle scent of the wet clay, and the cries, groans, and grunts made me feel like a voyeur watching an private, sexual act. But somewhere in the middle of the performance, Cassils broke away from pounding the clay and circled in front of the audience, standing briefly in front of each of us, breathing heavily in our faces and gently brushing their hands over the front of our bodies.

This gesture of physical connection with the audience snapped me out of my single-minded focus on Cassils and brought my attention to the crowd of observers. The flash bulbs illuminated the faces of the people standing directly across from me, under the hulking form of the plaster David, all of them hushed and intent. The shift in perspective made me see Cassils in relation to the audience and to the artworks around them. One of my favorite moments was when Cassils climbed atop the mass of clay, a living, breathing, kicking, punching work of art atop an unfeeling pedestal, dwarfed by the giant David behind them. There was something heroic about their actions, their challenge to the canon of art history, so vividly embodied by the plaster casts in the hall, with their ideal–and gender specific–male and female forms.

The performance ended as suddenly as it had begun, and Cassils left us standing in the darkness and, now, silence of the cast hall. For a moment, everyone held their breath, but then people around me began to clap. I suppose it’s conventional to clap after a performance to show appreciation for the artist, but it didn’t feel like the right response to something so powerful. It felt like I had just witnessed a religious ritual or a painful birth. In the Bible, we read that “God formed man of the slime of the earth: and breathed into his face the breath of life, and man became a living soul” (Genesis 2:7). Cassils gives birth to ideas and images, emphasizing the pain and violence of the process of creation. Their intimate and compelling performance suggests the limitations of the physical body even as it embraces the body as the perfect work of art.

Cassils performed “Becoming an Image” in the historic cast hall of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts on Friday, December 2, 2016, as part of an ongoing exhibition of their work, “Melt/Carve/Forge: Embodied Sculptures by Cassils,” which will remain on view through March 5, 2017.